How Communities are Overcoming Systemic Barriers to Climate Action

Forest Cover 70 brings together powerful case studies and firsthand testimonies from GFC member groups and allies in Bangladesh, Bolivia, Chile, Morocco, Panama, and Zambia. This edition exposes how extractivism and corporate-driven “green” solutions act as systemic barriers to gender-just, community-led real solutions to the climate and biodiversity crises, by reinforcing structural inequalities and threatening the rights, lands, and lives of Indigenous Peoples, local communities, women, and youth. In parallel, the case studies also highlight how communities are resisting and overcoming these barriers, and how their collective action can inform and strengthen global policy debates.

Download Forest Cover 70 in PDF

English

Español | Français (coming soon)

Introduction

Transformative Change is Needed for Real Solutions to Flourish

By Jana Uemura (Brazil) and Oli Munnion (Portugal), Global Forest Coalition Climate Justice and Forests Campaign Co-coordinators

Across the globe, the climate crisis is increasingly being addressed through narratives that promise “green” transitions without challenging the very structures that created the multiple and intersecting crises we face. Multilateral efforts to mitigate climate change, reverse biodiversity loss, and halt deforestation have failed us, clearly shown by the fact that after 30 rounds of climate negotiations, there still wasn’t even enough consensus at COP30 to directly mention a fossil fuel phaseout or implement a realistic plan to protect remaining forests.

Instead, mining for so-called critical minerals, large-scale tree plantations framed as restoration, carbon markets presented as conservation, and extractive industries rebranded as climate solutions dominate international policy spaces. These approaches externalise environmental and social costs onto Indigenous Peoples, local communities, women, and youth, particularly in the Global South and the very areas most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. They allow fossil fuel use, overconsumption, and corporate concentration of power to continue largely unchecked.

Frontline communities are increasingly aware of this hypocrisy and are not standing idle. This issue of Forest Cover brings together concrete cases by Global Forest Coalition member groups and allies in six countries—Bangladesh, Bolivia, Chile, Morocco, Panama, and Zambia— which collectively expose the limits of market-driven and extractivist climate responses. At the same time, they document how communities are advancing real solutions that are rooted in the realities of their territories, centering human rights, gender justice, and collective governance, and rejecting carbon markets and the financialisation of nature.

Mining for so-called critical minerals, large-scale tree plantations framed as restoration, carbon markets presented as conservation, and extractive industries rebranded as climate solutions dominate international policy spaces.

Read together, the articles demonstrate that meaningful climate and environmental action requires transformative change across economic, social and political spheres, not incremental adjustments to the status quo, or putting faith in market forces to solve problems that are largely a result of the dominant capitalist economic model.

Interconnected Struggles, Shared Patterns, Real Alternatives

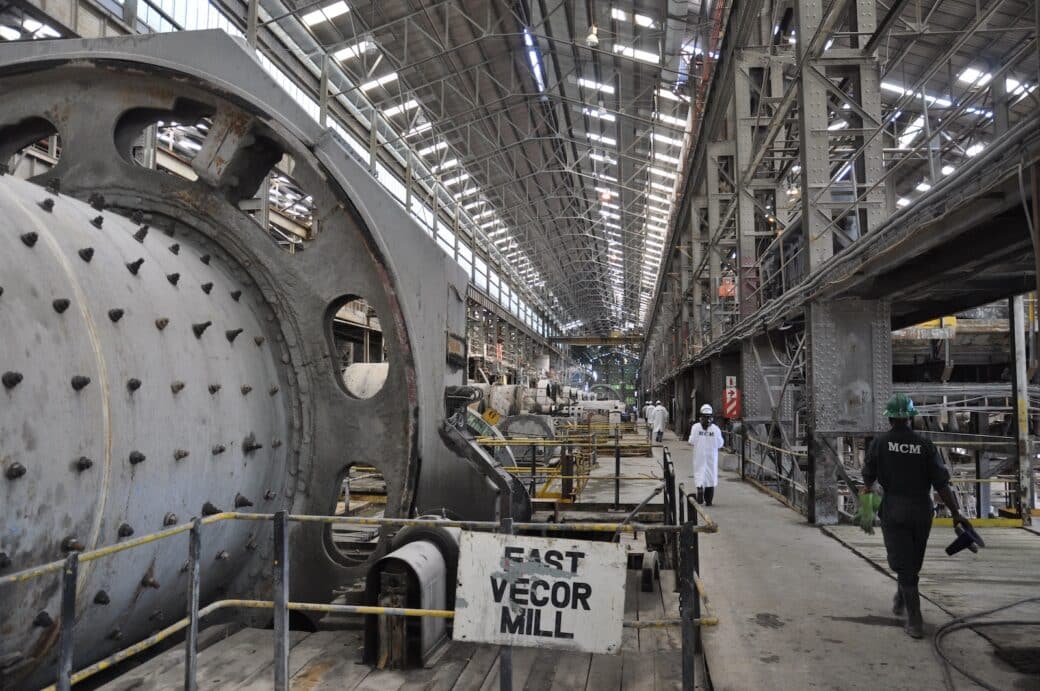

In Zambia, the case study written by GFC member group Zambia Social Forum (ZAMSOF) reveals the contradictions at the heart of the global green energy transition by exposing how the global demand for copper, driven by electric vehicles and renewable energy infrastructure, reproduces extractive sacrifice zones. This mirrors patterns seen in other articles in this issue, where climate-branded industries deepen pollution, dispossession, and gender inequality rather than delivering local benefits.

Drawing on interviews conducted in July 2025, the article documents persistent sulphur dioxide emissions, unsafe water sources, and widespread land dispossession; all impacts borne disproportionately by women. Women’s roles as primary caregivers and food providers mean they walk longer distances for water and fuel, face increased exposure to pollution, and experience heightened insecurity due to land tenure systems that exclude them from compensation and decision-making.

Despite mining revenues reaching tens of millions of dollars monthly, local benefits remain negligible, revealing how extractive “green” economies reproduce colonial patterns of wealth extraction. At the same time, women-led cooperatives and youth initiatives demonstrate viable alternatives, including agroecology, seed saving, and community-based energy solutions—real solutions rooted in autonomy and resilience rather than extraction.

The article by Centro de Desarrollo Ambiental y Humano (Center for Environmental and Human Development, CENDAH) on the Gunadule people of Gunayala offers a powerful counter-narrative to market-based climate solutions. For decades, the Gunadule have protected one of the most biodiverse forest and marine territories in the region through sacred, biocultural relationships with nature. When approached with REDD+ (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation Plus) and “blue carbon” market-based proposals, the community chose not passive rejection, but informed collective deliberation.

After internal discussions, the Gunadule concluded that carbon markets would subordinate their ancestral practices to the logic of commodification, thereby restricting cultural use of forests and undermining self-determination. In 2023, the General Guna Congress formally approved a Protocol rejecting REDD+ and carbon market initiatives, while affirming climate actions aligned with their own cosmovision and territorial plans.

Women, as guardians of land and culture, played a central role in this process, articulating concerns about dependency, corruption, and loss of autonomy. This case directly challenges the assumption that carbon markets are necessary to protect forests and highlights the importance of non-market approaches.

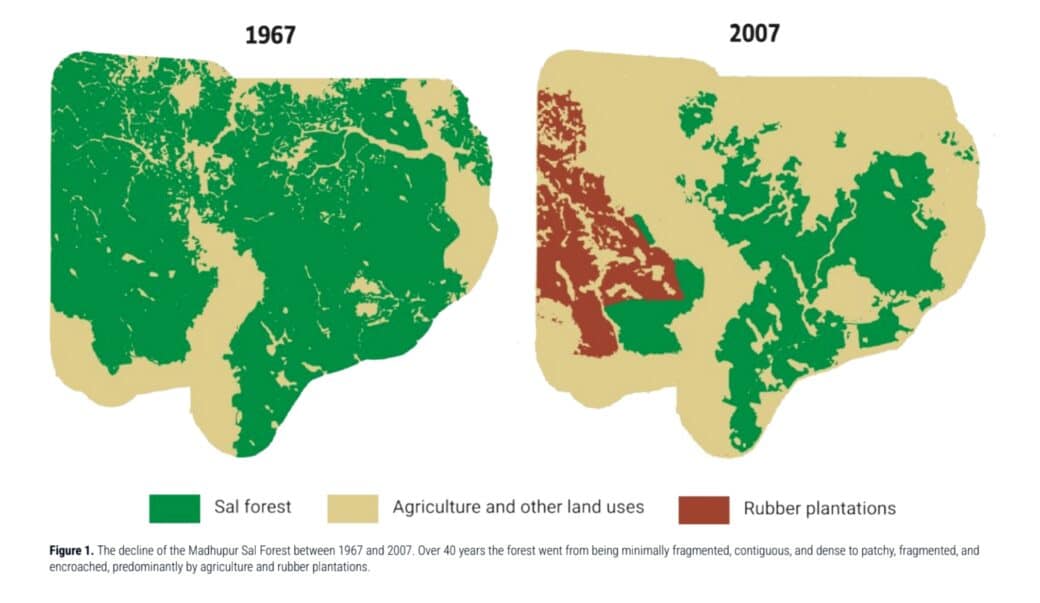

In Bangladesh, the article by the Bangladesh Environmental Lawyers Association (BELA) traces the dramatic decline of the Madhupur Sal Forest, where state-led “social forestry” programs, rubber plantations, and commercial agriculture (often funded by international development banks) have replaced native forests and undermined Indigenous Garo custodial rights. GIS data indicate that forest cover declined from 68.3% in 1967 to 29.8% in 2007, alongside the expansion of rubber plantations and settlements.

Although a landmark High Court ruling in 2019 recognised Indigenous custodial rights and mandated forest restoration, implementation was delayed for years and remains incomplete. The article highlights how Indigenous women suffer compounded injustices—land loss, criminalisation, gender-based violence, and erosion of matrilineal systems.

The case study underscores a crucial lesson: legal recognition alone is not transformative change. Without gender-just implementation, restitution, and a fundamental shift away from commercial forestry paradigms, forests and communities remain at risk. This directly echoes the IPBES warning that structural barriers (colonial governance systems, economic incentives, and exclusionary decision-making) must be dismantled to enable real solutions.

The contribution by Fundación Solón documents a concrete example of transformative action: the declaration of municipalities and Indigenous territories free of mining in Bolivia’s Amazon region. Facing an explosive expansion of gold mining (driven largely by illegal operations and massive mercury contamination), municipalities such as Alto Beni and Palos Blancos, together with Indigenous territories of the Mosetén and T’simane peoples, enacted local laws and pursued legal action to defend their rivers, forests, and agroecological economies.

These territories demonstrate that alternatives to extractivism are not theoretical—agroecological cacao production, community governance, and women’s leadership have sustained livelihoods while protecting ecosystems. The successful rulings of the Plurinational Constitutional Tribunal affirm municipalities’ rights to protect health and the environment, even in the face of national-level resistance. Women’s leadership is central throughout this struggle, illustrating how gender justice is inseparable from territorial defense.

This experience challenges international climate policies that continue to frame mining as a prerequisite for decarbonisation and resonates strongly with global calls for free territories—territories free from extrativism, mining, deforestation, wildfires, oil exploitation, and gender violence.

The article on Mapuche women in Chile, by Colectivo VientoSur and Red por la Superación del Modelo Forestal situates extractivism within a long colonial history of land dispossession, racialized violence, and monoculture forestry. Industrial plantations of pine and eucalyptus covering millions of hectares have destroyed native forests, dried water sources, and criminalised Indigenous resistance, while being promoted internationally as climate-friendly forestry solutions.

Mapuche women are at the forefront of land recovery, agroecology, seed preservation, and spiritual practices that restore relationships with Ñuke Mapu (Mother Earth). Their actions challenge not only corporate power but also state structures that exclude Indigenous voices from decision-making. As the article shows, real solutions are inseparable from cultural survival, self-determination, and gender justice.

The final case study, by the Indigenous Peoples of Africa Co-ordinating Committee (IPACC) and Fédération Nationale des Femmes de la Filière d’Argane(National Federation of Women in the Argan Sector, FNFARGNANE), highlights the argan forests of southern Morocco as a living example of a cultural forest shaped by centuries of Indigenous stewardship. Indigenous Amazigh women possess deep ecological knowledge of argan trees and have sustained agrosylvopastoral systems that protect biodiversity, prevent desertification, and support livelihoods.

Today, climate change, prolonged drought, and the monopolisation of argan oil markets by private companies threaten both the ecosystem and women’s rights. Despite these pressures, women’s cooperatives and the National Federation of Women in the Argan Sector are organising to defend access rights, promote fair trade, and uphold traditional governance. This case reinforces a central message: solutions rooted in traditional peoples’ knowledge and women’s leadership are already delivering climate resilience, yet receive a fraction of the financing directed toward false, market-based solutions.

Finally, we draw together the common themes from these articles and make the case that in order for multilateral policy processes to succeed in avoiding the worst impacts of climate change and biodiversity loss, transformative change in our approach to tackling these huge crises must be at the foundation of mitigation efforts moving forward.

Who Pays for the Clean Energy Transition?

The Gendered Impacts of Mining in Zambia’s Copperbelt

As the world races to secure copper for electric vehicles, women in Zambia’s Copperbelt are paying the price. In Mufulira, mining drives global “green” ambitions while leaving behind poisoned air and water, lost livelihoods, and entrenched gender inequalities. This article spotlights women-led resistance and innovation and calls for urgent action to hold corporations accountable, uphold community rights, and centre women’s leadership in a just, sustainable transition.

By Gershom Kabaso and Mkondo Lwamba, Zambia Social Forum (ZAMSOF), Zambia

Mufulira, a mining town in Zambia’s Copperbelt Province, offers a stark illustration of the paradox of extractive economies. Copper from its mines powers global industries and, increasingly, the push for so-called green technologies, such as electric vehicles (EVs). Yet for local communities, the costs of extraction have been devastating: polluted air and water, deforestation, displacement, and deepening poverty. Women and other underrepresented groups bear the heaviest burdens while being sidelined from decisions that shape their lives and livelihoods.

Copper has long been the backbone of Zambia’s economy, accounting for around 80% of export earnings and 10% of GDP, while employing only a small percentage of the population. The town of Mufulira has been central to this history since copper mining began there in the 1930s. Successive waves of colonial companies, state ownership, and privatisation have all extracted immense wealth, yet left behind impoverished communities, polluted land, and weakened livelihoods.

Today, Mopani Copper Mines continues this legacy, producing over 8,000 tons of copper monthly (worth some $80 million), with plans to expand thanks to $1.1 billion in investments from the United Arab Emirates. However, local benefits remain negligible: contributions to the municipal council are minimal compared to profits, while communities endure the consequences of air and water pollution, biodiversity loss, and degraded farmland.

The recent surge in global demand for critical minerals threatens to deepen these patterns. In 2023, Zambia and the Democratic Republic of Congo signed an agreement to create a Special Economic Zone for EV battery production, aiming to boost copper output to more than three million tonnes annually. While framed as part of a green transition, this push risks replicating extractive harms, with women and marginalized groups paying the highest price. The question remains: who truly benefits from this so-called clean future, and who bears its costs?

In July 2025, the GFC member group ZAMSOF visited the area to hear directly from those affected. We spoke with more than 30 community members—including women and youth, civic and community leaders, health workers, and faith leaders—to understand the impacts firsthand.

Gendered Human Rights, Environmental, and Socioeconomic Impacts

The impacts of mining in Mufulira are wide-ranging and severe. According to multiple studies and information gathered during interviews with community members in July 2025, communities in Kankoyo township endure persistent sulphur dioxide emissions, which corrode housing materials and cause respiratory illnesses. Water contamination from tailings and underground operations leaves many households without safe sources of drinking water. Farmland has been degraded or seized, leaving thousands at risk of displacement.

Although the mine installed technology that improved the capture of sulphur dioxide emissions—from less than half during the years 2007 to 2013, to more than ninety percent between 2014 and 2018—a study by the University of Zambia still found unsafe levels in the air. In Kankoyo, for example, average sulphur dioxide levels in 2017-2018 were about 16 percent higher than Zambia’s own safety guidelines.

Women are disproportionately affected. As primary providers of food, water, and fuel, they must walk longer distances to fetch firewood and water, often facing gender-based violence along the way. Land tenure insecurity compounds their vulnerability, with women frequently excluded from land allocation and compensation processes. Compensation for displacement is often gender-blind, overlooking women’s land rights under customary tenure and their reliance on farming for household food security.

According to local community members in Mitundu, nearly 100 hectares of farmland have been earmarked for mining exploration by Chilibwe Mining Company, placing approximately 2,000 farmers at risk of displacement. Women are most at risk of losing both livelihoods and homes.

The threat of dispossession is heightened by the fact that consultations have been limited to scoping meetings with business representatives, excluding government and civil society. According to local community members, no process of free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) has been carried out with affected farmers, leaving them outside critical decision-making. The fear of displacement among these 2,000 farmers reflects findings from a 2018 study on land tenure insecurity among smallholders by Charles K. Mulila and Mary Mwape. Such insecurity deepens rural vulnerability, with women farmers hit hardest due to their dependence on agriculture for food and income.

In Mufulira, men are largely employed in underground mining jobs such as drilling and blasting, while women are pushed to the margins—working in catering, cleaning, petty vending, or on small farms that struggle to survive on polluted soils. This reinforces cycles of economic exclusion, even as women shoulder disproportionate environmental and social burdens.

When compensation is offered, it is often inadequate and gender-blind—failing to involve women in decision-making, overlooking their land rights under customary tenure, and neglecting the disproportionate impact on women’s livelihoods and economic security.

Meanwhile, the health impacts of pollution fall heavily on women and children, as women face greater exposure from household activities and informal work, and children’s developing bodies are more susceptible to toxins.

Although no formal statistics exist on the loss of forest cover due to mining in the region, women in the communities told us that they had lost access to wild foods, mushrooms, caterpillars, and medicinal plants as deforestation and biodiversity loss escalate. The destruction of these resources further undermines household food security and erodes traditional knowledge.

Community-led Resistance and Solutions

Despite the many challenges they face, communities in Mufulira are far from passive victims. Women, youth, and local cooperatives are leading efforts to resist extractive harms and build alternatives. Organisations like the Vizense Women and Youth Group have diversified livelihoods through livestock production and vegetable farming, reducing dependence on mining and strengthening food security.

As one community member noted, “We cannot rely on the mine for everything; we must feed ourselves and create our own opportunities.”

The Kamukolwe Multipurpose Cooperative, composed largely of women, practices traditional seed saving, avoiding hybrid varieties that deplete soils. Farmers have embraced agroecology, producing organic fertilizer from decayed vegetables and indigenous tree foliage. Youth networks have invested in briquette machines and biogas digesters, providing affordable and sustainable energy that reduces reliance on charcoal and hydroelectric power.

These initiatives show the potential of local knowledge and innovation. By drawing on generational farming practices, protecting forests, and creating renewable energy solutions, communities are forging pathways to resilience. Importantly, they are also reshaping decision-making processes, ensuring that women, youth, and marginalized groups are included in local development efforts.

Women’s Leadership for Climate Justice

Mufulira represents the contradictions of the global extractive economy: while its copper fuels global industries and the transition to electric vehicles, local communities live with displacement, environmental devastation, and entrenched gender inequalities. Women are on the frontlines of these impacts, yet they are also at the forefront of resistance and innovation.

A just transition must recognize and support women’s rights, knowledge, and resilience. This means enforcing Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) for affected communities, mainstreaming gender-sensitive approaches in mining governance, and ensuring that the Environmental Protection Fund, a mandatory state-run financial mechanism that mining companies pay into to fund environmental rehabilitation, is used to compensate those harmed by extractive industries. It also requires holding corporations accountable through robust social and environmental safeguards and stronger international frameworks, such as the UN Binding Treaty on Business and Human Rights.

Ultimately, climate justice cannot be achieved through a new wave of extractivism. Communities in Mufulira show that alternatives exist—rooted in agroecology, renewable energy, and collective resilience. A fairer future lies in centering women’s voices and leadership, ensuring that the drive for a green transition does not repeat the injustices of the past.

Panama’s Gunadule Indigenous People Reject REDD+

in Favor of Strengthening Ancestral Conservation Practices

This article explores how Panama’s Gunadule Indigenous people are defending their autonomous territory and ancestral conservation practices in the face of megaprojects, carbon markets, and REDD+ initiatives promoted as “climate solutions”. It documents the Gunadule’s collective rejection of REDD+ and extractive development models, highlighting how ancestral agroforestry systems and women-led stewardship offer effective, rights-based climate solutions. The article finds that externally imposed, market-driven conservation schemes undermine Indigenous self-determination, cultural integrity, and long-standing ecosystem protection.

By Geodisio Castillo, Center for Environmental and Human Development (CENDAH), Panama

The Gunadule are an Indigenous community in Panama’s Comarca of Gunayala, which stretches across northeastern Panama and the Darién region, where Panama and Colombia meet, a megadiverse jungle area that links Central and South America. As of 2023, Panama had 112,319 Gunadule inhabitants, about a third of whom currently resided in the Comarca (a semi-autonomous region similar to a province).

Gunayala was among the first autonomous Indigenous territories in Abya Yala(the Americas), having been designated 100 years ago, after the Gunadule Revolution. It occupies 2,307 km² of the Panamanian Caribbean coastline, of which98.6% is forested, as well as an archipelago of 365 islands. In addition to forested areas, the Comarca encompasses extensive mangroves and a rich marine zone, both of which are crucial for community livelihoods and coastal protection.

The Gunadule have a sacred and biocultural relationship with Mother Nature, which they view as the source of life. This worldview underpins their historical commitment to the management, conservation, and sustainable use of biodiversity. Their cultural heritage, passed down mainly by Gunadule women, includes the Dulegaya language, ancestral knowledge regarding seed preservation, and the healing practices of women healers and midwives, known locally as siggwi gaed. Gunadule women also preserve sacred artistic designs expressed through molas, a textile art made from cotton panels, masterfully sewn by hand, and often depicting the natural world. These textiles are a powerful symbol of culture and identity.

The Gunadule territory is home to rich biodiversity, including 670 recorded species of flora, five species of mangrove trees (red, black, white, piñuelo, and buttonwood), 440 species of birds (including parrots and macaws), and 58 mammals, as well as marine-coastal ecosystems, estuaries, seagrass beds, and coral reefs.

Through their ancestral knowledge and spiritual connection to nature, the Gunadule people have protected their territory despite the climate change-related challenges they have faced, which have deeply affected their way of life. Gunadule women, in particular, contribute to ecosystem recovery and ensure food and cultural security in the face of climate change by preserving a diversified farming system known as nainu (or “one’s own land”). This ancestral practice respects the earth’s natural cycles, conserves native seeds, and maintains soil fertility.

Threats to Ancestral Conservation Practices

The rich biodiversity and culture of the Gunayala region face serious threats. One specific challenge stems from infrastructure and energy projects, which, under the guise of “climate solutions” promoted by public entities, are implemented without the free, prior, and informed consent of the communities.

A project to build an electricity grid connecting Colombia and Panamato allow “clean energy”to be transported from the southern part of the continent to the north, and the Mortí-Mulatupu highway connecting eastern Gunayala with Panama City, are two key examples that show how the development of megaprojects generates social, cultural, and environmental impacts in territories that are already being conserved through ancestral practices.

These megaprojects have also resulted in local resistance. Although environmental impact studies were conducted, the Gunadule people formally rejected both megaprojects through Resolution No. 1, dated March 27, 2023, which remains in force. The projects did not provide any direct benefits for the community, which chose to protect the forests and reject a development model that threatens their worldview and deep relationship with nature.

The Gunadule have learned that extractive projects and initiatives proposed by outside actors, such as companies and large conservation NGOs, frequently fail to address the structural causes of climate change and biodiversity loss. Instead, in cases such as the resettlement of the Isberyala community, they can have negative consequences and lead to poor adaptation for communities.

Rejecting REDD+

Carbon markets are another threat facing the Gunadule. Historically, the Gunadule community has been cautious about the false solutions to climate change proposed by external actors.

In 2011, the U.S.-based company Wildlife Works Carbon (WWC) proposed a pilot study to develop a REDD+ project in Gunayala. WWC is involved in the carbon credit business and has been linked to sexual abuse scandals in Kenya and harmful agreements in the Democratic Republic of Congo,Brazil, and other countries in the Global South. Its project in Gunayala aimed to finance the protection of 99,415 hectares of forest ecosystems in the Corregimiento de Narganá, through an agreement with 28 communities and the Guna General Congress. This autonomous government body is the highest political, administrative, cultural, and spiritual authority within the Comarca of Gunayala (known as Onmageddummagan in the local language).

WWC promised US$1 million in startup capital to guarantee initial payments to the Guna General Congress and the Narganá Community Carbon Fund for infrastructure development, hiring of Gunadule personnel, and the initiation of operations, including forest patrols. Subsequent financial support was to be obtained from the sale of REDD+ credits on the voluntary carbon market.

Under the agreement, the Gunadule would grant WWC the rights to carbon credits in the area for 30 years, while ownership of the land and forests would remain unchanged. Cultural and ancestral uses of the forests would be maintained as long as they did not harm the carbon value (forest mass), which would jeopardize profits. In other words, the Gunadule people’s ancestral conservation practices would be conditional on commercializing the forests based on their capacity to act as carbon sinks.

Instead of rejecting the project on principle, Gunadule communities opted to participate actively in vetting it, even though the Guna General Congress had asked the local NGO Earth Train (later renamed Geoversity) to expedite the pilot study. Local representatives attended workshops to learn about the project and then shared the information with their communities for discussion. Ultimately, the REDD+ project was never implemented in Gunayala, allowing the Gunadule’s ancestral conservation practices to continue uninterrupted.

When companies hold workshops to co-opt and convince communities of the supposed benefits of REDD+, they interfere with community dynamics of organization, management, and territorial stewardship and disrupt local planning processes. Instead of strengthening the communities’ capacity to protect their rights, reduce structural inequalities, and promote self-determination and conservation practices, they sidetrack them with debates over top-down projects that impose prohibitions on their culture, traditions, and ways of life.

“If they’re going to give us money in exchange for no work, that will make our women and youth turn lazy. Just waiting around for money, being dependent on the supposed millions of dollars from selling the carbon [capacity] of our forests [isn’t part of our culture], it’s a scheme that we’re not ready to manage. We do not accept the project because money corrupts us,” said Leida Smith, president of the Rural Women’s Association of Digir (AMRD, in Spanish).

The Guna General Congress established a commission in 2021 to develop its own climate change documents grounded in the Gunadule cosmovision or worldview, resulting in a protocol to defend Gunadule autonomy and spirituality against outside projects. In 2023, the body formally approved a “Protocol on carbon initiatives and REDD+,” which rejects these schemes in defense of local territory and culture, and a “Protocol on climate change initiatives that do not include REDD+” to bolster community autonomy and territorial defense.

Briseida Iglesias, a leader of the women’s group Bundorgan (“Sisters”), explained that climate solutions cannot come from outside but must be informed by ancestral knowledge of harmony with nature. Self-determination and the right to make decisions are the keys to keep this vision alive. “By rejecting REDD+ projects, we reaffirm our right as women to self-determination and control over our ancestral lands. We will not allow outside actors to manage our forests under schemes that could compromise our future. We don’t need external models to conserve our forests; we have thousands of years of wisdom that is valid and effective in the fight against climate change,” she said.

Gunadule Women, Guardians of Life and Ancestral Knowledge

Gunadule women play crucial roles in community organization, coordinating effective and strategic environmental preservation work that helps combat the climate crisis. Bundorgan, which coordinates women’s groups in the region, helps raise awareness of how women’s active participation in forest management and agriculture contributes to biodiversity protection.

The implementation of agroforestry systems, such as family gardens or nainu, is a clear example of a real climate solution that increases agricultural production for food security, using sustainable techniques such as “zero tillage” and allowing fallow land to regenerate. This ancient practice also involves sustainable harvesting of forest resources, including seeds, to ensure the permanence of the forest cover.

Gunadule women preserve and transmit ancestral knowledge through two fundamental cultural pillars: mola textiles, which represent their worldview, identity, and resistance—including symbols from mythology, nature, and daily life—and duleina, traditional medicine based on the use of native plants. Through these practices, they strengthen their cultural and botanical knowledge and their role as guardians of community health. Despite the magnitude of their contribution in the socio-environmental, cultural, and health spheres, the support they receive to strengthen these practices is inadequate.

Gunayala maintains its own real solutions to the climate crisis and seeks to promote individual and collective action, as outlined in its 2015-2025 regional strategy. Activities highlight the nainu family agroforestry production system as a concrete and effective practice of millennial regenerative agriculture. Sustainable soil rest (regenerative fallow) in these systems helps combat soil degradation and restore soil, preserve biodiversity, capture more carbon, produce botanical gardens, and build resilient cultural and human landscapes, providing an environment for living well, or yeeriddodisaed, weligwariddodisaed in the Guna language.

The family nainu helps prevent soil erosion, conserves water, and protects biodiversity. The classification of nainu includes crops on agroforestry plots established on flat coastal lands and coral islands; crops on slopes, which are called nainu nussuggwa (young plot), nainu sered (old plot), and nainu matuled (stubble).

The agricultural and conservation practices of the Gunadule people promote plant diversity within the same plot, thereby improving soil health and encouraging wildlife, without the use of agrochemicals. These ancestral techniques not only preserve plant and animal life but also enhance resilience to climate change and mitigate the environmental crisis by sequestering carbon in soils and forests.

It also strengthens community participation, particularly among women and children, as it provides a space for family gatherings, recreation, and environmental education, thereby supporting cultural preservation, food security, and the transmission of traditional knowledge to future generations.

In addition, the nainu system contributes to the restoration of key ecosystems (wetlands, mangroves) and the planting of native trees, strengthening the effective management of the Gunayala Comarca. The application of this model in the country’s vulnerable communities, with the active participation and leadership of Gunadule women, could guarantee real climate solutions that respect human rights and territorial autonomy.

Consent and Participation are the Key

Analyzing the gap between discourse and climate action is essential to understanding the failure of many top-down conservation initiatives and the emergence of false solutions. Although recognition of Indigenous Peoples is encouraged in some multilateral spaces, real solutions are not promoted with the same force, nor are direct resources allocated to develop community conservation initiatives led by Indigenous communities and rooted in their ancestral practices. Without the participation and consent of local communities and actors, particularly women and youth, superficial market-based initiatives are unsustainable and generate local resistance.

Many initiatives only address the symptoms (e.g., planting trees) rather than the systemic causes of the crisis, such as industrial agriculture and infrastructure megaprojects. Furthermore, the limited incorporation or non-recognition of nature’s common goods in participatory restoration projects results in a lack of policies to reduce inequalities and promote climate and gender justice, which are urgently needed in Gunayala and globally.

The Struggle for Indigenous Custodial Rights and Ecosystem Protection in the Madhupur Sal Forest

Amid the rapid destruction of Bangladesh’s Madhupur Sal Forest, Indigenous communities and environmental lawyers have challenged state-sanctioned deforestation through a landmark legal battle. Drawing on field research and a historic 2019 High Court ruling, this article reveals both the promise of judicial recognition of Indigenous custodial rights and the persistent failures in implementation. The findings show that without gender-just, community-led enforcement, legal victories alone cannot safeguard forests or Indigenous livelihoods.

By Rysul Hasan, Rehmuna Nurain, and Bareesh Chowdhury, Bangladesh Environmental Lawyers Association (BELA)

Bangladesh faces a severe and ongoing crisis in forest conservation, marked by conflicting official estimates and a steady decline in forest cover. Although the state has a constitutional obligation to protect natural resources, forest loss has continued at an alarming pace. Between 1990 and 2015, Bangladesh lost an estimated 2,600 hectares of forest annually, reducing overall forest cover to well below the globally recommended minimum of 25% for ecological balance. Among Bangladesh’s major forest ecosystems, the plain sal forests of central Bangladesh, once extensive and ecologically rich, have suffered some of the most severe degradation.

The Dwindling Madhupur Sal Forest

The Madhupur Sal Forest is a tropical moist broadleaf forest ecosystem that once extended across large parts of central Bangladesh and eastern India. Today, only about 8,436 hectares remain. Dominated historically by sal (Shorea robusta), the forest supported rich biodiversity, including large mammals and diverse plant species, many of which are now locally extinct.

Once home to species such as the Bengal tiger and one-horned rhinoceros, the forest has been reduced to fragmented patches with severely diminished ecological integrity. This decline has been driven by illegal logging, land grabbing, commercial plantations, and misguided state-led afforestation and settlement programs.

The Madhupur Sal Forest has long been home to Indigenous Garo and Koch communities, whose livelihoods, culture, and survival are inseparable from the forest. For generations, these communities practiced sustainable forest use, including shifting cultivation and the harvesting of non-timber forest products such as medicinal plants, fruits, and tubers.

However, statist forest policies, commercial exploitation, and the failure to recognize Indigenous custodial rights have systematically restricted these practices. Indigenous communities have increasingly been treated as encroachers within their own ancestral lands, fuelling long-standing tensions with the Forest Department.

Satellite imagery provides clear evidence of the systematic conversion of Madhupur’s native sal forest into agricultural land, rubber plantations, and settlements between 1967 and 2007. In that time, forest cover declined from 68.3% to just 29.8%, while rubber plantations, agriculture, and settlements expanded rapidly, fragmenting the remaining forest and accelerating biodiversity loss.

Large-scale land allocations by the state have been among the most destructive drivers of forest loss in Madhupur. More than 400 hectares were allocated to the military for firing ranges, while over 2000 hectares were converted into rubber plantations. Commercial fruit cultivation, particularly pineapple and banana monocultures, has further replaced native forest ecosystems.

Donor-funded social forestry programs, supported by agencies such as the Asian Development Bank and UNDP, have exacerbated these impacts. Rather than restoring native sal forests, these initiatives prioritised fast-growing exotic species such as eucalyptus and acacia. These plantations depleted water resources, degraded soil quality, and provided minimal benefits to Indigenous communities, revealing a profound disconnect between conservation rhetoric and on-the-ground realities.

BELA’s Intervention and the Legal Struggle

Alarmed by the rapid degradation of the Madhupur Sal Forest, the Bangladesh Environmental Lawyers Association (BELA) undertook a detailed field survey in 2008 to document ecological damage and human rights violations. The investigation recorded 8,632 families (40,625 people) living within the forest, including Indigenous Garo (4,129 families), Bengali Muslim (4,372 families), and Hindu (131 families) communities.

The findings of this survey would later form the evidentiary basis for BELA’s public interest litigation seeking legal protection of the forest and recognition of Indigenous custodial rights.

The findings revealed widespread commercial land conversion for rubber and fruit plantations, institutional abuse, and systematic exclusion of Indigenous people from forest governance. Only 45% of promised social forestry benefits reached participants, while hundreds of forest dwellers faced harassment, false cases, and violence.

Institutional failures exacerbated the problem. The social forestry program mismanaged 2,861 hectares, with only 45% of promised financial benefits reaching participants. The system enabled widespread abuse, with 621 forest dwellers facing false and intimidating defamation cases and 3,188 reported incidents of illegal logging. These systemic issues undermined both forest conservation efforts and community trust.

The Indigenous Garo community suffered severe consequences from these changes. Traditional livelihoods were disrupted, with a 70% loss of medicinal plant species and threatening a further 27 species of edible and medicinal tubers that Indigenous People depend on. The forced transition to cash crops reduced average household income by 38%. Culturally, matrilineal land inheritance systems were undermined, and sacred forest sites were destroyed in 63% of surveyed Garo villages. However, such forestry development initiatives have never benefited women in particular. Women face land loss, physical attacks, false cases, and poverty. As they lose their higher status in a matrilineal society and become landless, they rely on exploiting forest resources for subsistence.

Despite comprising 48% of the population, Garo families received only 30% of social forestry benefits. Harassment by officials was reported by 92% of respondents, culminating in the deaths of two activists between 2000 and 2004 during land rights protests against a proposed “National Park Development Project”. Among them was Piren Snal, a Garo youth who was shot by police and forest guards for defending the sal trees sacred to his people.

The Legal Case and Landmark Judgment

Armed with these findings, in 2010, BELA filed a Public Interest Litigation (No.1834/2010) case in collaboration with two Indigenous Peoples’ organizations: Joyenshahi Adivashi Unnayan Parishad and Jatiya Adibashi Parishad. The petition made several demands to protect the forest ecosystem and rights: proper demarcation of forest boundaries, protection of native species, legal recognition of the Garo and Koch communities’ rights, a halt to all unauthorized commercial activities, a ban on harmful plantations, and social forestry reform.1

After nine years, on 28 August 2019, the High Court delivered a landmark judgment ordering the creation of a high-powered committee to develop a long-term conservation plan, demarcate forest boundaries, conduct a door-to-door settlement survey, and ensure community participation in forest protection. Crucially, the judgment explicitly recognized the Garo and Koch peoples as Indigenous inhabitants of the Madhupur Sal Forest, affirming their lawful settlement and custodial rights, despite the state’s longstanding refusal to recognize Indigenous Peoples.

Despite its historic nature, the judgment remained largely unimplemented for five years. Only in late 2024, following national political upheaval and the formation of an interim government, was the mandated committee finally established, including Indigenous representatives and BELA. Some progress has since been made, including the commencement of surveys and commitments to halt exotic plantations and initiate restoration efforts.

Delayed Implementation and Continuing Violations

While the long-delayed formation of the conservation committee was welcomed, structural problems remain. In a recent field visit, the BELA team interviewed several community organisers and members on the current situation in the Madhupur Sal Forest.

Yuzin Nokrek of Joyenshahi Adibashi Songha, an Indigenous organization, says the Forest Department still operates under an outdated mindset that prioritises economic gain through the commercialization of forest land over ecological restoration or protection of forest-dependent communities, who are viewed with hostility. He also noted that there are currently 231 Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation (SLAPP) cases lodged against Indigenous Peoples, and that the Ministry of Environment, Forests, and Climate Change has promised to withdraw them.

Another local community organizer, Probin Chishim, revealed how the Forest Department is entangled in leasing forest land for monoculture cultivation, which undermines forest biodiversity. He said 300 acres of forest were given to the Air Force for a shooting range, of which 192 acres have now been leased out for commercial farming. This is evidence that the forest is not disappearing under encroachment by impoverished Indigenous locals, but rather state-sanctioned exploitation.

In 2020, the Forest Department abruptly destroyed the small fruit cultivation of an Indigenous woman named Basanti Rema, who was branded as a “land grabber” by the authorities. The land she tended was taken and given to Bengali settlers for commercial cultivation, and she and many of her community now work as labourers on the land they once stewarded. Rema spoke of the disappearance of medicinal plants—an often-overlooked consequence of forest loss—and how this drives the Indigenous community toward costly pharmaceuticals, severing a link between the community and their traditional way of life.

The Madhupur Sal Forest remains in a state of acute vulnerability. Drone footage captured how thick stretches of green canopy give way to large expanses of cleared land, creating an illusion of a healthy forest hiding destructive practices just under the surface. Demarcation and door-to-door surveys have only just begun after a five-year delay, causing considerable damage. The Sal Forest is resilient, but can only survive if it is immediately protected from commercial leasing, land clearing, and monoculture plantations.

A legal judgment, unless implemented and ensuring gender equality, is insufficient, no matter how historic its contents in offering recognition to Indigenous communities. Legal recognition for women makes no difference if their displacement, harassment, gender-based violence, criminalization, and the destruction of their cultural and ecological heritage and traditional livelihoods are not halted. The communities, particularly Indigenous women and youth, deserve fair treatment and restitution.

While the Bangladeshi constitution enshrines principles of gender equality, a profound gap persists between this promise and reality, particularly concerning land and resource rights. For instance, despite legal provisions, patriarchal customs frequently prevent Indigenous women from independently owning, inheriting, or controlling land, leaving them economically vulnerable and dependent. This tenure insecurity is exacerbated by their systematic exclusion from policymaking bodies that determine the fate of the very forests on which they depend. Consequently, when their land is seized or their livelihoods are destroyed, Indigenous women face a dual injustice: as members of a marginalized community and as women within that community. They often lack the means to seek redress, facing significant barriers to accessing justice, from a lack of legal awareness to discrimination within dispute-resolution bodies. Therefore, a judgment cannot be considered truly implemented unless it specifically halts the violent subjugation of Indigenous women, ensuring they have the legal power and access to justice to claim their rightful place as custodians of their heritage. Only then can restitution be considered fair and complete.

A legal framework is needed to replace the outdated, gender blind, colonial mindset of resource extraction with a harmonious, gender-just, and sustainable approach that balances biodiversity and ecosystem protection with the fulfillment and realization of the full rights of Indigenous communities, particularly women and youth, and BELA’s case is a first step toward that. However, this will require action from the ground up, led by the communities and supported by allies, and a change in the mindset and mandate of the administration to not treat Indigenous Peoples with hostility. Otherwise, the Madhupur Sal Forest will fade into memory, and the heritage and traditions of these communities will disappear with it.

Territories Free from Mining are Showing the Way to Save the Amazon

As gold mining spreads across the Bolivian Amazon, this article documents how Indigenous territories and agroecological municipalities are leading a powerful grassroots response by declaring themselves mining-free. Through legal actions, community mobilization, and agroecological economies, these territories are defending rivers, health, and biodiversity while exposing the dangers of state-sanctioned extractivism. The article highlights the decisive role of Indigenous and rural women, whose leadership has been key to sustaining resistance, expanding territorial autonomy, and inspiring similar initiatives across the Amazon.

By Pablo Solón, Fundación Solón, Bolivia

Gold mining in Bolivia is like an epidemic spreading through the Amazon. It has expanded rapidly over the past two decades, particularly in the Department of La Paz, which encompasses both the high-altitude altiplano and vast tropical lowlands such as Madidi National Park. Reports indicate that the number of mining operations and concession requests has surged, reflecting a major increase in industry activity across the region.

The growth is also evident in the land area targeted for gold mining. Mining is increasingly moving into previously untouched territories, including sensitive Amazonian forests and protected areas. Satellite monitoring and environmental reports show that the scale of land affected by mining has multiplied dramatically, highlighting the sector’s rising footprint on both the landscape and local communities.

The proliferation of mining in the Amazon might seem impossible to control, but there is still hope to stop the scourge. Although the price of gold has risen to a record $5,000 per ounce at the time of publication, there are places where residents are determined to put a stop to mining, including in the municipalities of Palos Blancos and Alto Beni in the Department of La Paz and some Mosetén and T’simane Indigenous territories.

The Gold Epidemic

The overwhelming majority of gold mining ventures in the Bolivian Amazon are illegal and lack valid permits or environmental licences. This is uncontrolled extractivism driven by capital from Colombia, Russia, China, Bolivia, and other countries operating behind mining cooperatives. There are over a thousand gold mining cooperatives, but fewer than ten trading companies oversee most gold exports. Drug trafficking is also present, and wherever you look, this open wound seeps outward.

Bolivia is one of the world’s largest importers of mercury, the chemical used to separate and concentrate gold. Some is used domestically, while the rest is smuggled into neighbouring countries with more restrictive laws. Once the mercury is released, bacteria transform it into its most toxic organic form: methylmercury, which enters the food chain of plants, fish, birds, animals, and humans.

A recent study found that the Esse Ejjas, T’simanes, and Mosetenes Indigenous Peoples who live downstream from gold mining operations in the Department of La Paz have levels of mercury in their bodies seven times higher than World Health Organisation limits. Methylmercury can cause irreversible damage to child development and to people’s nervous, digestive, renal, and cardiovascular systems.

Women are particularly vulnerable to the effects of mercury exposure, as it causes a higher incidence of hormonal disorders and reduced fertility. Indigenous women face double discrimination, based on their gender and ethnicity, due to their lack of access to resources, health services, and education. They are also traditionally the primary caregivers, which increases their workload and undermines their mental health when children in the community suffer from cognitive and physical development issues as a result of mercury exposure.

Gold mining damages biodiversity and removes millions of tonnes of soil and rock, deforesting land and altering the course of rivers. Every year, municipalities beset by mining suffer calamities as a result of their own actions; floods, landslides, and mudslides are not natural disasters, but rather tragedies caused by extractivism.

Some fish that swim thousands of kilometres to spawn upstream lose their sense of direction in murky water caused by the removal of the riverbed. In addition to the impacts on human health and nature, there are also social impacts: encroachment on Indigenous territories and protected areas, inhumane working conditions, and the spread of sexual exploitation, drugs and alcohol, violence and conflict.

The Bolivian state receives a royalty of just 2.5% on all gold exports. In some years, gold smuggling competes with legal exports. All governments understand the serious problems caused by gold mining in the Bolivian Amazon, yet instead of stopping it, they facilitate the destruction. Mining Law No. 535 of 2014 was tailored to the needs of mining cooperatives. In a decade, mining operators have had the deadline for completing their updating procedures renewed eleven times. Governments have been permissive towards mining cooperatives because of their capacity for mobilisation and the voting base they represent. Taking advantage of their power, mining cooperatives and the businesspeople who hide behind them are demanding more and more: access to protected areas, new areas for exploitation, and greater flexibility in already weak environmental regulations. No one wants to stand up to this industry, save a few municipalities and Indigenous territories dedicated to agroecology and ecotourism that have resolved to halt the expansion of gold mining in the Amazon.

Agroecological Ventures

Agroecological development began in the 1970s in the municipalities of Alto Beni and Palos Blancos, when migrant farmers from the highlands founded the El Ceibo Cooperative Centre to produce organic cacao. They began exporting in 1987. Today, El Ceibo has at least 48 cooperatives, 1,300 farmer members, and a cacao and chocolate processing plant in El Alto, which exports 40% of its organically certified products abroad.

Cacao is grown on small plots of 3 or 4 hectares without agrochemicals or GMOs. Farmers harvest cacao beans and dry them in the sun, then compost the husks to enrich the soil. Over the years, both municipalities have begun to use agroforestry systems to produce citrus fruits, papaya, bananas, copoazú, passion fruit, and other products.

The municipalities are on either side of the Alto Beni River, and several watercourses flow through their territory, where cooperatives and entrepreneurs have submitted 58 applications to mine for gold. The Indigenous territories of the Organisation of Mosetén Indigenous Peoples (OPIM) and the T’simane Mosetén-Pilón Lajas Regional Council (CRTM-PL), which partially overlap with these municipalities and a protected area, have also seen 41 mining applications. Mining operators constantly encroach on these municipalities and Indigenous territories in an attempt to settle illegally.

Mining-Free Municipalities

Since 2017, several organisations have issued statements and taken action against mining encroachment. In 2021, Palos Blancos and Alto Beni passed municipal laws declaring themselves agroecological municipalities free of mining activity and pollution. In 2024, the Legislative Assembly of the Department of La Paz passed a law endorsing both municipalities’ commitment to agroecology, free from mining pollution.

That same year, the Vice Presidency of the Plurinational State of Bolivia filed a conflict of jurisdiction2 against the municipal law of Alto Beni with the Plurinational Constitutional Court. The Vice Presidency argued that the regulation of mining rights is an “exclusive jurisdiction” of the national government and not of the municipality. This legal action was a slap in the face for both municipalities’ agroecological authorities and organisations. More than 80% of the population in those municipalities had voted for the Movimiento al Socialismo(MAS) Party and Vice President David Choquehuanca in the 2020 federal elections.

Delegations from both municipalities repeatedly travelled to the capital to explain to the Vice President and his staff that they did not want to take any powers away from the national government. Municipal and social leaders explained that their municipalities are mining-free because they have prevented the settlement of illegal miners over the years, and there are still no miners operating legally with authorisation from the state mining agency — known as AJAM for its initials in Spanish. Their argument was compelling: if there is mining, there is pollution, and if there is pollution, they will lose their certification as organic cocoa exporters. In short, their agroecological vocation is incompatible with mining activity.

In 2025, the Plurinational Constitutional Court ruled3 that the municipality of Alto Beni acted constitutionally in compliance with its municipal powers to preserve its population’s health and environment. It cannot grant or revoke mining rights granted by the national government through the AJAM; however, it does have full municipal powers to defend its rivers and agroecological practices.

Both municipalities are backing a bill in the National Assembly to guarantee agroecology and extend this protection against mining to other “Indigenous and peasant municipalities and territories with an ecotourism and agroecological vocation.”

Restrictions on Mining Rights

Alongside the declaration and consolidation of the laws on agroecological municipalities free from mining, in June 2023, the Ombudsman’s Office filed a legal action4 before the Palos Blancos court to reverse an AJAM resolution authorising a consultation process for the granting of a mining contract in that municipality. The judge ruled to overturn the AJAM resolution and urged Alto Beni and Palos Blancos to inform the AJAM of “the geographical areas free of mining exploitation for restriction.”

A year later, the 11th Pan-Amazonian Social Forum (FOSPA), which brought together 1,500 representatives from different social sectors, adopted a mandate to promote the creation of municipalities and territories free from deforestation, wildfires, mining, oil exploitation, and gender violence.

The authorities and social organisations of Palos Blancos and Alto Beni subsequently presented the AJAM with geo-referenced maps of their municipalities, requesting that this area be restricted for the granting of mining rights in compliance with the ruling of the Palos Blancos judge.

The municipalities invited the Vice President and AJAM to Alto Beni to speak with leaders of social organisations. In August 2024, before a gathering of 300 representatives of agroecological, Indigenous, and women’s organisations, the Vice President and government authorities donned green t-shirts bearing the slogan “mining-free municipalities.” The event concluded with the signing of a document in which AJAM committed to temporarily suspending the granting of mining rights.

Authorities and leaders from both municipalities continued to press for the suspension to take effect. In 2025, the Plurinational Constitutional Court issued a new ruling5 on the 2023 decision by the Palos Blancos judge, granting full guardianship to the municipalities and signaling the obligation to adopt the necessary measures to guarantee the rights of the Beni River.

Indigenous Territories Free from Mining

The OPIM and the CRTM-PL Indigenous territories, which partially overlap with Palos Blancos and Alto Beni, also approved resolutions of territorial assemblies declaring themselves mining-free. Both Indigenous territories, which are legally titled as Tierras Comunitarias de Origen (Native Community Lands) and have been recognised as Indigenous Nations of the Plurinational State of Bolivia under the 2009 Constitution, sent geo-referenced maps of their territories to the AJAM for restriction, as did the municipalities of Palos Blancos and Alto Beni.

In the case of the CRTM-PL, which includes the protected area of Pilón Lajas, the mining authority responded by saying that the entire area is restricted by various legal provisions, some of which date back to the late 1900s. Although AJAM’s response formalises the restriction on mining activities, it reveals that this entity did not fully comply with this restriction because it did not promptly reject more than ten mining applications initiated in this protected area and Indigenous territory. In the case of the OPIM, AJAM stated that its territory is partially restricted by various legal provisions and raised the challenge that these territories should be treated in accordance with their status as Indigenous Nations.

Several Indigenous territories, such as the CRTM-PL, have rejected the “fragmented consultations” carried out only within the particular communities where mining is planned. They argue that all communities in their Indigenous territory should have a say because the impacts are felt throughout the territory. Therefore, they assert that the declaration of a mining-free Indigenous territory is a decision that must be respected and not fragmented through rigged consultations, and that a mining-free Indigenous territory means that all communities — with free, prior, and informed consent, and without any pressure from mining cooperatives — have made a decision that covers their entire territory.

The Fight Against Illegal Mining

A long struggle involving municipal laws, court rulings, and social mobilisation succeeded in suspending the granting of mining rights in the areas described in this article; however, it did not put an end to mining encroachments. At present, most legal proceedings are suspended, but illegal incursions by unscrupulous miners continue.

The two agroecological municipalities of Palos Blancos and Alto Beni have worked out internal environmental control regulations to combat illegal mining and are working constantly to prevent this scourge from penetrating their territory. In a widely publicized case on 13 July 2025, a delegation of more than 50 representatives of the OPIM and officials from the municipality of Palos Blancos travelled down the Alto Beni River to investigate a report of illegal mining. Upon arrival, they found a 30 x 30 metre pool, a hydraulic backhoe, an industrial motor pump, a large sorting machine, a camp that had just been hastily evacuated, more than 5,000 litres of diesel buried on the beach, and a businessman who turned out to be none other than the deputy minister of mining under former President Jeanine Añez. The businessman claimed the machinery was being used to open a road, but the commission transferred him to the Palos Blancos police. There, they took his statement, and municipal officials and OPIM leaders filed a criminal complaint against him for illegal mining, diesel smuggling, and clear-cutting.

The investigation of this complaint revealed a series of inconsistencies in the judicial investigation process, leading to an inter-institutional coordination protocol against illegal mining in the municipalities of Palos Blancos and Alto Beni. The protocol was developed jointly by the Vice Presidency, AJAM, the Public Prosecutor’s Office, the Ministry of the Environment, the Ministry of Government, the Attorney General’s Office, the Ombudsman’s Office, OPIM, CRTM-PL, and the two municipalities. Organisations in the region say that if there are no effective sanctions against those responsible for mining encroachments, they will continue to try to circumvent the restrictions on mining activities. Therefore, inspections and rigorous social and municipal monitoring of the rivers must be accompanied by state action to prevent and sanction offenders, removing them from the territories and avoiding impunity.

Women’s Leadership

Women have been deeply involved in struggles to defend their municipalities and territories against the mining epidemic in Bolivia. The Alto Beni and Palos Blancos Municipal Councils are both chaired by powerful women. The OPIM, CRTM-PL, CIPTA, CPILAP, and others have Indigenous women’s organisations that work very closely with the mixed Indigenous community organisations. An example is the Organisation of Mosetenes Indigenous Women (OMIM), which works alongside the OPIM in all its actions. Meanwhile, the CRTM-PL is chaired by Magalí Tipuni, a woman of great strength and determination.

Women continue to be at the forefront of continuing struggles, which, fortunately, are serving to inspire others. Since the 11th Pan-Amazonian Social Forum was held in the Bolivian Amazon in June 2024 with participants from nine countries, the example set by these municipalities and agroecological organisations has spread to other regions. February 2025 saw the First meeting of agroecological and ecotourism Indigenous municipalities and territories, which brought together the municipalities of Rurrenabaque and San Buenaventura and incorporated Indigenous territories in the north of La Paz in a leading role.

In October 2025, the Tacana Indigenous People’s Council (CIPTA), located in the municipalities of San Buenaventura and Ixiamas in the Department of La Paz, also declared itself mining-free and submitted its geo-referenced maps to the AJAM so that it could proceed to restrict mining rights in its territory.

The Central Organisation of Indigenous Peoples of La Paz (CPILAP), which comprises 11 Indigenous territories, has filed a class action lawsuit that has been responded to favourably, suspending the granting of mining rights in the Beni and Madre de Dios Rivers and several of their tributaries.

Replicating the Cure

The example is spreading to other municipalities around the country and agroecological regions. In late October 2025, the “Second meeting of municipalities and territories free of mining” was held, culminating in a set of 50 proposals to halt mining. These include: “Promote the creation or expansion of municipal protected areas as a strategy to restrict mining and other extractive activities” and “strengthen women’s participation in agroecological and ecotourism activities.”

The fight to permanently restrict mineral resource exploitation in Indigenous municipalities and territories is far from over. The plaintiffs want the restriction to be made official and permanent rather than temporary. They also want to cover their entire territory and have all mining applications rejected, clearing their territories of mining grids requested in the mining registry.

The experience of these Indigenous municipalities and territories shows that it is possible to curb gold mining by strengthening and expanding agroecological, sustainable, and democratic alternatives built at the local level.

The concept of territories free from extractivism has been gaining strength. This is demonstrated by the example of Yasuní National Park in the Ecuadorian Amazon, where the majority of the population voted in a national referendum to leave the oil underground. The struggle for territories free from extractivism is the struggle for self-determination from below in the face of governments that are increasingly coopted by destructive logic of power, which leads to ecocide.

Community Approaches to Overcoming the Climate Crisis:

Mapuche Women Confront Extractivist Destruction in Chile

This article provides a critical examination of the legacy of the extractivist colonial economy in Latin America and the Caribbean and related land grabbing, environmental destruction and gender inequality. It also shows experiences of community conservation in Chile as ways to overcome the climate crisis, biodiversity loss and deforestation.

By Javiera Rodríguez Olguín, Red por la Superación del Modelo Forestal / Colectivo VientoSur / Fundación Pongo

The Latin America and Caribbean region has been marked by a strong legacy of resistance against colonialism, racism and territorial dispossession, key vectors of capitalism and Western notions of modernity. Historically, mechanisms of power and domination were imposed that have favored universalist values and destroyed the social and cultural fabric of various communities and peoples. Extractivism, one of the main contemporary expressions of colonial violence and plunder, continues to reproduce and redefine an idea of civilization that favors the destruction of life over care for territories, and these processes are essential to understanding Latin American realities.

Various popular uprisings throughout history have made clear the environmental devastation wreaked by large corporations in territories across Latin America, which has involved land grabbing, social and environmental conflicts, gender inequality and human rights violations, among other impacts. False solutions to the climate crisis are currently having clear repercussions across the region, threatening communities and ecosystems, but it is also important to bring the legacy of colonialism to bear in discussions of climate justice as a structural barrier to implementing real solutions in the territories.

Despite challenges, communities are promoting ancestral conservation practices as alternatives that resist domination and colonialism. Women in all their diversity, youth, gender diverse people and the elderly are playing key roles in the maintenance of traditional knowledge, resistance struggles, and worldviews that involve defending nature and living beings.

Women-led community action to fight climate change

Indigenous, peasant, and Afro-descendant women are disproportionately affected by the capitalist, extractivist, and patriarchal model that is responsible for causing climate change and deforestation. Many have lost their lives as a result of this model. According to a report by Global Witness, nearly 2,100 environmental defenders were assassinated between 2012 and 2023.

Meanwhile, forests continue to be disputed territories. In the last decade, primary forest loss doubled in the nine countries of the Amazon region, opening the door to patterns of land concentration for monocultures, cattle ranching, mineral resource exploitation, carbon markets, and illicit economies. Despite the pressures on Indigenous and local communities, they continue to resist and work to reassert and reconnect with their ancestral identities and ways of life.

In Chile, extractivism has caused enormous environmental degradation, including the loss of native forests, 38% of which is due to pine and eucalyptus plantations. These monocultures cover some 3 million hectares. Two of the country’s largest forestry companies, Forestal Mininco and Forestal Arauco, constitute a serious threat to communities where they operate, having been responsible for land grabbing and harassment, persecution, and criminalization of the Mapuche, as well as environmental destruction and human rights violations.

In Chile’s southern Biobío region, the province of Arauco has historically experienced high poverty rates and inadequate public policies, resulting in poor living conditions for residents. One of the towns most affected by the forestry model is Curanilahue, where there is a particularly high concentration of land ownership by big forestry companies. Forestal Arauco, for example, owns 63.1% of municipal public lands (known as suelo comunal), and another 16.8% is owned by Mininco and its subsidiaries. Although some 80% of the territory is controlled by the forestry giants, local community conservation initiatives exist that are strengthening collective organization, territorial protection, and political participation as concrete strategies for protecting nature’s common goods. Many of these practices are rooted in ancestral knowledge, and the fact that communities continue to resist the assault by extractivism demonstrates their deep commitment to achieving real conservation results.

Also in Arauco Province, Lleulleu Lake in the Nahuelbuta mountain range is of great spiritual, cultural, and ecological importance to the Mapuche people. Situated between the mountains and the coast and surrounded by native trees, this is considered one of the cleanest lakes in South America. This is no accident; Mapuche communities have actively protected the lake in the face of contaminating activities such as salmon farming and industrial forestry.

For the Mapuche, Lleulleu Lake — spanning 4,300 hectares — and the forests around it are not simply a “natural resource,” but rather, an integral part of the ancestral territory of Wallmapu, as the area is known locally by Indigenous inhabitants. This profound sense of belonging has fueled many victories, including the recovery of 20,000 hectares of land by Mapuche communities who reasserted their right to autonomously determine their territorial management model. For the Mapuche, the land (mapu) is sacred. In their territorial demands and processes of taking possession of the land, they mention ñuke mapu, which is about not just reasserting their territorial rights but also reestablishing their spiritual relationship with nature and affirming their ways of life and worldview.

Mapuche women play key roles in recovering land from big forestry companies that sell pine and eucalyptus. For many Indigenous women, taking back land involves more than just regenerating the local ecosystem; it also extends to acts of resistance against the forestry companies that have usurped Mapuche land. Three women’s organizations that have worked to bring about change by strengthening food sovereignty, traditional knowledge, and cultural identity are the Red de Mujeres Mapuche de Chiloé, la Asociación Nacional de Mujeres Rurales e Indígenas (ANAMURI), and the Red de Estudiantes Mujeres Mapuches (REMM).

A Mapuche woman leader in Wallmapu who preferred to remain anonymous for safety reasons said: “There are more women than men active in the struggle – growing food, working the land. We do this for our children because tomorrow we may not be here, but they will. We drink clean water, we eat healthy food, we practice our culture. ….We do this autonomously, which frees us from companies and the state. People are imprisoned, people have lost their lives — but the important thing is that we are resisting.”

The Red de Mujeres del Lafkenmapu, a group of Mapuche and peasant women from the town of Tirúa in Arauco Province, Biobío, has been carrying out actions since 2013 that are focused on promoting environmental recovery, propagating native species, preserving organic seeds, maintaining traditional knowledge for gardening, and caring for water and life.

Meanwhile, in Penco in the Province of Concepción, Biobío, the women of the Asociación Indígena Koñintu Lafken Mapu lead acts of resistance against the Penco-Lirquen LNG Terminal and Canadian company Aclara, which extracts rare earth minerals used in the manufacturing of electrical components for cell phones, computers, electric vehicles, wind turbines, and defense systems. They believe in overcoming obstacles through formal legal processes, as well as keeping their traditional spiritual practices alive.

“I defend my territory because I know about the meaningful places here,” said María Patricia Flores Quilapan of the Asociación Indígena Koñintu Lafken Mapu. This is ancestral territory where we have our ngen protectors [spirits in nature, according to Mapuche cosmology], water as medicine, and the ancestral spirits which remain alive.”

These Mapuche and peasant women from community organizations in Southern Chile are part of the historical legacy of leadership in defending their territories, spiritual practices, and traditional knowledge, as well as resilience that transform challenges into struggles that build strength.

Making resistance visible to rethink development models

Industrial forestry companies in Chile, such as Forestal Arauco and Forestal Mininco, have an over 50-year history of seizing vast tracts of land and destroying water resources and biodiversity. Overcoming social inequality and repairing the damage they have caused could take decades, and to do this, it is essential to guarantee access to land; respect free, prior and informed consent for communities; ensure respect for human rights; mobilize resources to implement policies that promote care and social justice; and facilitate spaces where communities can have access to decision-making power. Another pending task is the pursuit of culturally appropriate justice so as to ensure dignified lives for the Mapuche community.

Just as women leaders from the Kukama Indigenous community in Peru successfully asserted the right to integrity and protection of the Marañon River, which flows from the Andes Mountains to the Amazon, Chile’s Indigenous and peasant women continue to overcome barriers to the protection of their lifeways and worldview. They continue to build territories of care based on their practices and collective action.

It is essential to recognize, fund, support, and build spaces for participatory training in order to rethink development models, just transitions, and policies for climate action. Promoting life, systemic transformations, and gender justice — all of which are crucial aspects of achieving climate goals, biodiversity action plans, and environmental justice — should be at the center of any action that seeks to preserve ecological balance.

Overcoming Challenges Through Gender Justice

The Symbiotic Relationship Between Amazigh Women and the Argan Forests of Morocco

The argan forests of southern Morocco, long stewarded by Indigenous Amazigh women, face unprecedented threats from climate change, drought, and private-sector monopolisation of argan oil production. Despite these pressures, Amazigh women continue to defend their rights, sustain cooperatives, and protect a unique cultural and ecological heritage recognized by UNESCO. Their story highlights both the vulnerability of the argan ecosystem and the resilience of Indigenous women leading the fight for climate, social, and gender justice.

By Dr. Handaine Mohamed, Indigenous Peoples of Africa Co-ordinating Committee (IPACC) and Jamila Id Bourrous, Fédération Nationale des Femmes de la Filière d’Argane (FNFARGNANE), Morocco

The argan forests of southern Morocco form one of the world’s most distinctive human–nature landscapes. For centuries, these unique forests have sustained Indigenous Amazighcommunities (also known as Berbers), with Amazigh6 women particularly holding deep ecological knowledge of the argan tree and depending on it for food, income, medicine, cultural traditions, and community identity. Today, however, the forests and the women who steward them face an unprecedented convergence of threats: deepening climate change, prolonged drought, rural out-migration, the socio-economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the aggressive expansion of private-sector argan oil production.