Gender justice and livestock farming: A feminist analysis of livestock and forest policy-making

The Glasgow Leaders’ Declaration on Forests and Land Use, signed in November 2021 during COP26, pledged to end deforestation by 2030. This is a full ten years later than the target set out in (and missed by) the Sustainable Development Goals. It is also a sad reminder of the fact that forests are still under constant threat all over the world, even though we know that to have any hope of stopping catastrophic climate change we have to urgently halt deforestation and restore forest ecosystems.

Agricultural expansion is the main cause of forest and biodiversity loss globally, and two of the big four drivers of deforestation are industrial meat and soy production. Women bear the impacts of forest loss disproportionately, particularly if they are from Indigenous, poor and marginalized communities. Forest loss can deprive them of their income, food security, and traditional knowledge. They are also key actors in forest conservation and sustainable food production, and should therefore be central to climate mitigation and biodiversity conservation efforts.

This edition of Forest Cover is a feminist perspective both on policies promoting the expansion of unsustainable livestock and feedstock farming, and efforts to address the wide-ranging impacts of these sectors. It consists of three comprehensive country-level case studies, supported by six articles exploring national and international contexts. Put together, they analyze the implications of these policies for women and their communities, and assess to what extent they contribute towards — or act as a barrier to — achieving gender justice.

Download the report:

English: web quality 5.5MB | low resolution 1.6MB

Spanish: web quality 5.5MB | low resolution 1.6MB

French: web quality 5.5MB | low resolution 1.6MB

For more information on GFC’s work on gender justice and climate action, please see our Gender Justice and Forests, and Unsustainable Livestock Production campaign pages.

Contents:

-

- Editorial: Feminist viewpoints are vital to getting livestock policies right

- The industrialization of livestock production in Togo and its heavy toll on pastoralist women

- In-depth case study: Bolivia’s burning issue: How cattle ranching and agroindustry policies are driving loss of livelihood for rural women

- Development banks are failing women

- In-depth case study: Ban grazing or give forests to livestock farmers? Nepal’s overgrazing dilemma is hitting women hardest

- Georgia’s “gender diet”: How intensive agriculture is destroying rural livelihoods and increasing gender inequality

- In-depth case study: In search of tekoporá: Gender considerations in industrial livestock farming in Paraguay

- Women and agroecology in Latin America: Voices from the ground

- A feminist perspective on recent efforts to decouple livestock farming from deforestation

Editorial: Feminist viewpoints are vital to getting livestock policies right

By Dennis Mombauer and Vositha Wijenayake, SLYCAN Trust, Sri Lanka

Forest ecosystems span over one third of the Earth’s land area and provide habitats for the vast majority of terrestrial biodiversity. From a global perspective, they regulate ecosystems, protect biodiversity, stabilize the climate, and sequester approximately 2.6 billion tons of carbon dioxide per year. For local communities, forests are a vital source of goods, services, and livelihoods. They guarantee community health and wellbeing, increase resilience to climate change, and hold great cultural significance.

Today, only half of the world’s forest area is left relatively intact. Climate change, forest fires, pests and diseases, invasive species, and droughts contribute to the destruction, degradation, and fragmentation of forest landscapes. In addition, the primary driver of forest and biodiversity loss is agricultural expansion, including unsustainable and industrial livestock farming, which is also a leading cause of anthropogenic methane emissions. The neo-colonial, market-driven, globalized exploitation of forest resources and landscapes accelerates climate change, reduces biodiversity, and poses an existential threat to the 1.6 billion people (one fifth of the world’s population) relying on forests for their livelihoods. However, communities, households, and individuals living in and around forests face disproportionate impacts from these issues.

Indigenous, poor, marginalized, and vulnerable communities depend on forest resources and ecosystem services as their socio-economic safety net in times of crisis. Often, it is women within these communities who pay the highest price for deforestation and forest burning, which can deprive them of their income, food security, and traditional roles as knowledge keepers and conservationists. Women in all of their diversity can face discrimination in multiple and intersecting ways, depending on their social status, ethnicity, age, class, sexual orientation and gender identity, amongst others.

These gender-related inequities can be addressed in various ways, including through policies, laws and regulations; integrated landscape management; forest conservation, rehabilitation, and restoration; capacity-building, awareness-raising dietary changes; community action; coalition-building; or financial instruments and technology. However, such measures must build on robust evidence to be effective and avoid replicating existing inequalities or power relations.

Gendered differences can be seen in access to and control over resources, equipment, and assets; land ownership and legal or customary rights; division of labor and daily activity profiles; gender roles, standards, norms, expectations, self-image, and institutional practices; information flows and local or traditional knowledge; participation in planning and decision-making processes at the household, community, or societal level; education and health services; risk management and social protection; and the distribution of benefits from forest resources.

Any intervention must stem from a deep understanding of gender-differentiated impacts, implications, contributions, capacities, constraints, and challenges, especially for Indigenous and rural women and girls and other underrepresented or marginalized groups. The case studies in this report highlight the importance of a country- and context-specific feminist viewpoint in policy-making related to livestock farming, that asks the key questions: How are women affected by official and unofficial forest management and the enabling socioeconomic environment? How are their roles recognized and seen by society and themselves? What are the levers of change to strengthen women’s rights, opportunities, and decision-making power?

The research undertaken by GFC member groups and allies as part of this publication has followed a feminist methodology developed by GFC members, which provides an intersectional lens through which to analyze policies that both promote and try to tackle the impacts of unsustainable livestock production. The research has been compiled into three comprehensive country-level case studies, supported by five articles exploring national and international contexts. It ends with an analysis of multilateral efforts to address the impacts of livestock farming on forests, and whether they can contribute to achieving gender justice.

In some cases, women are custodians of forest ecosystems with a wealth of traditional and experience-based knowledge, including on spatial plant distribution, seasonality, phenological cycles, harvesting limits, sensitive niches, and threats. In other cases, they play a pivotal role for the traditional pastoralist way of life and sustainable livestock farming. Gendered differences can be found on the consumption side, for example through “menu segregation” and unequal meat consumption among men and women, but also regarding food production and distribution. In Sri Lanka, for instance, women diversify the nutritional base by cultivating “genetic gardens” and domesticating food and medicinal plants in home gardens across the country.

Forests are ecosystems of immense diversity, and so are the human communities that depend on them. Similarly, there are huge differences between unsustainable industrial livestock farming and traditional grazing practices, pastoralism, or small-scale integrated crop-livestock systems. Action on forest conservation and sustainable livestock practices must be informed by local and gender-sensitive knowledge; for example, through disaggregated and participatory data collection or the provision of dialogue platforms and safe spaces for women and women’s groups to share their experiences and proposals.1

Forests are more than just physical landscape features. They have social, economic, and cultural dimensions that connect differently to the lives of men and women. Women tend to be more affected by forest loss and face additional risks and vulnerabilities, and they are also key actors when it comes to forest conservation and sustainable food production. Their contributions are essential, and holistic forest management is not possible without taking women in all their diversity into account, acknowledging their unique capacities, and ensuring their full participation in decision-making.

Forest protection goes beyond planting trees and ensuring they are not cut down. Forest protection means protecting the climate, protecting biodiversity, protecting livelihoods, and empowering local communities in specific, inclusive, participatory, and gender-transformative ways, recognizing especially the roles of women, girls, Indigenous Peoples, and other marginalized or vulnerable groups.

1 GFC (2021). Methodology for Case Studies to Understand the Underlying Causes of the Impact on Women of Policies and Initiatives to Address the Main Drivers of Forest Loss.

The industrialization of livestock production in Togo and its heavy toll on pastoralist women

By Martina Andrade and Kwami Kpondzo, FoE-Togo

Togo has had an alarming deforestation rate of 4.5% per year, and in response, the government adopted a National Forestry Policy in 2011 designed to halt deforestation and increase forest cover to 30% by 2050 (up from 6.8%).1

The policy identified the expansion of agriculture and uncontrolled transhumance2 as key drivers of forest degradation, and set out strategies to strictly control pastoral activities. For example, specific corridors were created for livestock to be moved though.

Alongside high deforestation rates, Togo also faces increasing demand for animal protein, which now outstrips production by 4.5 kg per capita per year and requires large imports. To address this, the government is supporting the construction of ranches, dairies and slaughterhouses. As well as increasing production, this is supposed to help “control and modernize the practice of international and local transhumance”.

The government’s dual policy strategy of controlling traditional pastoralism while promoting intensive livestock farming is likely to have significant impacts on women, given their central role in traditional livestock farming and the fact that transhumance is their primary economic activity. On top of this, while the Forestry Policy acknowledged women’s important role in fighting deforestation, it did not recognize the barriers they face in gaining equal access to land and resources, or how dependent their livelihoods are on agriculture.

Although 51% of people engaged in the agricultural sector are women, their role is undermined in pastoral societies. As a consequence, 42% of female farmers have no education compared to 15% of male farmers and the estimated income gap between male and female farmers is 44%. The majority of pastoralist societies are also largely male-dominated and patriarchal, despite the fact that women are key actors in wealth generation and subsistence. Their responsibilities include planning the routes that herds will follow, guiding the animals through their migrations and strengthening social links with local populations in grazing areas. Women pastoralists are also deeply knowledgeable about grazing conditions, water availability and caring for their animals.

Despite this vast knowledge and responsibility, it is still seen as the role of men in a family to sell animals at market, and herds are still largely seen as belonging to men. Because of this, women’s economic contributions to the household aren’t recognized, nor is their key role in preventing herder-farmer conflicts through the work they do at the community level.

Togolese policies to control pastoralism focus mainly on basic technical parameters such as where animals can graze, and treat the role of women in transhumance and its importance to their livelihoods as secondary. This perpetuates discriminatory social norms and acts as a barrier to guaranteeing equal access to resources. The same pattern is now being repeated in the way that intensive livestock farming is being promoted by the Togolese government.

1 Efforts to increase forest cover center around a target of over 600,000 hectares of commercial tree plantations, which would make plantations the dominant tree cover type in the country. https://globalforestcoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/AFR100-plantations-briefing.pdf

2 Transhumance is a form of pastoralism that involves the seasonal movement of livestock between grazing pastures, either within national borders or internationally.

Bolivia’s burning issue: How cattle ranching and agroindustry policies are driving loss of livelihood for rural women

By Pamela Cartagena and Carmelo Peralta, CIPCA, Bolivia

In Bolivia, extensive livestock production1 and mechanized agriculture cause deforestation, the degradation of ecosystems, greenhouse gas emissions and other environmental impacts, as well as harm to livelihoods. More than 7 million hectares have been deforested, an area about the size of Belgium and the Netherlands combined, with extensive livestock production and agribusiness being the main causes.

According to MapBiomas Amazonia, agricultural and ranching activities in Bolivia’s lowlands and yungas2 increased the agricultural and ranching frontier by an estimated 3.7 million hectares between 1985 and 2018, to a total of just over 5 million hectares. During that same period, the country’s forest cover decreased by an almost equal amount, going from about 49 million hectares to 45.3 million hectares.

The volume of Bolivia’s beef exports increased by 550% between 2016 and 2020, (from 2,457 to 15,962 tons), with China being the biggest market and buying 84% of Bolivian beef. Increased beef production has resulted in forest burning and forest fires to clear land for agriculture during dry seasons, and in recent years policies designed to promote agribusiness in the lowlands have accelerated the amount of land burned and deforested in the country.

Methodology

There are no clear figures on the impacts of deforestation and fires on Indigenous and peasant communities, much less on how rural families and their livelihoods are affected, and what the gender-differentiated impacts are. Therefore, the main objective of this case study is to analyze the impacts of national and regional policies and measures that promote livestock production and hence deforestation and forest burning on women and the livelihoods of rural families.The gender focus allows us to identify, interrogate and evaluate the discrimination, inequality and exclusion faced by women. Meanwhile, the livelihoods focus allows us to understand the impacts of policies that incentivize livestock production on the income and economic wellbeing of rural families.

To achieve this aim, research was conducted into policy measures that fuel deforestation, forest burning and forest fires at the national level. Semi-structured interviews were also carried out in 12 peasant communities, three of which were in the northern Amazonian region, six in Guarani Indigenous communities in the Chaco region and three in Guarayas Indigenous communities in the eastern region of Bolivia. The interviewees consisted of nine women and three men, all adult heads of household and leaders of peasant and Indigenous organizations. They were selected for their knowledge of agriculture-related policies and projects being carried out in their regions and their contextual knowledge of the dynamics at play. The women interviewed were between the ages of 33 and 51, and men were ages 57 to 59. The interviews explored gender roles in the family and community; livelihood strategies and their dependence on natural resources; participation in decision-making; and the impacts of projects and policies on women and men.

Agricultural policies and their impacts at the national level

Regulations that have promoted deforestation and forest burning in Bolivia in recent years (see table) have had repercussions throughout the different regions of Bolivia, and their impacts are clear at the local level. They include Laws 337, 502, 739 and 952, which legalized formerly-illegal land clearing for agriculture and cattle ranching between 2013 and 2017 under the pretext of food production

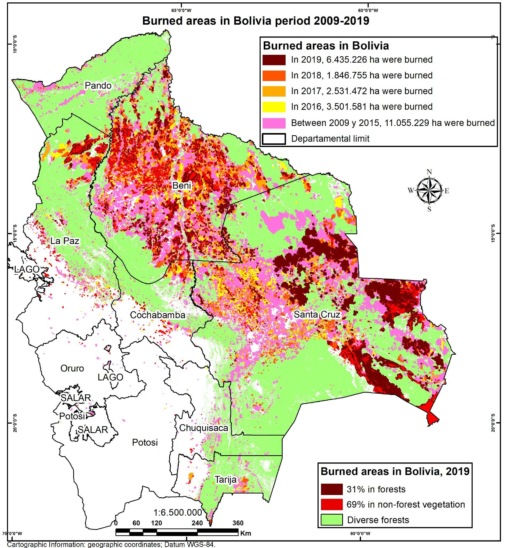

Supreme Decree 3973 of 2019 was particularly controversial because it authorized land clearing for agricultural and livestock activities in the Amazon, Chiquitania and the Eastern Chaco regions. This included clearing in forest vocation lands3 in the departments of Beni and Santa Cruz, which had previously been limited by local land management plans. As a result, that same year, a record 6.43 million hectares were burned throughout the country, and mainly in those two departments (see map). Large areas were also burned in 2020 and 2021, 4.54 and 1.50 million hectares respectively, with extensive forest loss again taking place mostly in Beni and Santa Cruz.

The government also passed Law 1171 in 2019 which allowed burning for agricultural and livestock farming purposes within certain limits, and stipulated fines for landowners that breached the limits. However, it has had little effect in the areas studied as illegal burning has continued unabated and the fines per hectare burned are so low that they do not discourage the practice.

National regulations incentivizing agricultural expansion and forest loss

| Year | Law | Purpose |

| 2013 | Law 337: support for food production and forest recovery | Applicable to private properties that are already titled or whose titling is in process and small and collective properties of Indigenous and peasant peoples that have been illegally deforested between 1996 and 2011. Land clearing is pardoned on the sole condition that they produce food. Low penalties and fines are established. |

| 2014 | Law 502 | Extends the term of the pardon under Law 337 for an additional 12 months. |

| 2015 | Law 739 | Extends the term of the pardon under Law 337 for an additional 18 months. |

| 2015 | Law 740: modifying the period of verification of social and economic function (FES, in Spanish) | Applicable to procedures for the reversion of agricultural properties that do not demonstrate any social and economic function. The period is extended from 2 to 5 years, which encourages deforestation on private property and consolidates the unproductive latifundios (large agricultural estates). |

| 2015 | Law 741: authorizing land clearing in small landholdings for agricultural and livestock activities | Applicable to small properties or community or collective properties and human settlements through an expedited and simplified Authorization Resolution. The amount of land free for clearing is extended from 5 to 20 hectares in permanent forest production lands with the purpose of fostering agricultural and livestock farming activities. |

| 2017 | Law 952: extending the registration deadline under Law 337 | Extends the registration deadline for the food production and forest restitution support program under Law 337 for an additional 27 months. |

| 2019 | Law 1171 | Authorizes burning for agricultural and livestock activities within certain parameters, with penalties for non-compliance including maximum fines of 16.4 Bs (2 Euros)/ha. |

| 2019 | Supreme Decree 3973: modification of Art. 5 of S.D. 26075 of 2001 | Applicable to private and community properties in the departments of Beni and Santa Cruz. Authorizes land clearing for agricultural activities in land that previously had to comply with a land-use plan or land-clearing plan approved by the competent authority. |

Source: created by the authors based on information from the Official Gazette of the Bolivian Government

Map of areas burned for agricultural and livestock activities in Bolivia 2009-2019

Source: created by the authors based on data from Fundación Amigos de la Naturaleza.

Local-level impacts of agricultural and livestock policies

Based on the interviews conducted in the three regions studied it was found that women, their livelihoods and the wellbeing of their families are highly dependent on natural resources. The loss of forests caused by burning and deforestation in these regions, in particular in 2019 and 2020 following the implementation of Law 337 and Supreme Decree 3973, has changed their lives significantly.

Impacts on livelihoods

Three specific impacts on livelihoods were identified by interviewees: lack of water for domestic consumption and agricultural production, pressure on natural resources like forests from cattle ranches and lack of opportunities to generate income due to the first two impacts and other socio-environmental factors. Both women and men believe that the environmental changes that they are experiencing and that impact their agricultural production such as irregular rains and frequent droughts are a result of deforestation in the area caused by unsustainable livestock farming and agribusiness.

In all three regions, most deforestation has occurred as a result of uncontrolled burning of pastures by large, private cattle ranching companies, which spread to communal forest areas used for collecting forest food crops and in some cases the agricultural land of peasant farmers. This resulted in significant loss of livelihood. For example, the loss of thousands of bee colonies has affected honey production in the Chaco region; and the Eastern region has seen the loss of forest areas used to pick cusi palm fruits (Attalea speciosa) and where Guaraya women traditionally gathered wild cacao (Theobroma cacao).

Competition for resources

Competition for productive resources is also a factor in the three regions, and large private properties with extensive livestock production often encroach on areas of community-owned forests, pastures and water sources so that cattle can graze. As well as hampering the agricultural production of Indigenous peasant farmers, this generates conflicts that often go unresolved given the power relations between the cattle ranchers and community members, with the latter often having to turn to the ranching companies for employment.

Shifting rural gender roles

The loss of opportunities to generate income from the small-scale processing and sale of products at the community level is a recurrent issue. It is clear that, if family livelihoods are lost (like harvesting forest products, agroforestry systems, small-holder crop and livestock production), it is women who will face the greatest difficulties. This is due to the fact that men often opt to leave the community in search of paid work, and rising levels of male out-migration have forced women to take sole responsibility for food production and leadership positions within the community. The increasing shift to women being heads of household in rural communities has not been recognized by state institutions.

Patriarchal land ownership structures

The impacts that women experience are worsened when the majority lack ownership of and the right to access, use and control land and forest resources in their communities. Since the introduction of large estates or haciendas5 in the early twentieth century, women were limited to reproductive and care-giving roles. Following agrarian reform and the abolition of the hacienda system, the collective land titling or reclamation process from 1990 to 2000 prioritized local customs in lowland peasant and Indigenous communities. Each community was given a legal title with an annex showing a list of titleholders, consisting of the men of the community only. The lack of gender sensitivity on the part of the authorities, in addition to the local patriarchal culture, prevented women from being included on equal terms with men as rights holders.

Exclusion from decision-making

Both men and women interviewees also reported that they lack opportunities to take action on and reverse the negative changes in their communities and territories that affect their livelihoods. Women’s perceptions of commercial ranching projects established near their communities in recent years are critical, and they generally have not been informed, consulted, or taken into account in the implementation of livestock-related projects and policies. As a result, many of them have failed, even where projects have focused on improving peasant livelihoods. For example, the government’s national cattle ranching program “Plan Patujú”, aimed to increase cattle numbers in areas such as the Amazon and lowlands of Bolivia. It distributed a certain number of head of cattle to peasant and Indigenous communities without considering feed, infrastructure, management and other inputs needed for sustainable cattle farming. In many cases, the cattle were sold or consumed by the communities.

The Guayara Indigenous Territory

One example that illustrates the effects of laws incentivizing burning and deforestation in the Eastern region of Bolivia is the Guayara Indigenous Territory (TCO, in Spanish), which is one million hectares in size. Despite its designation as communally-owned Indigenous land, burning by large-scale ranching companies to create pastures is frequent in the TCO, bringing with it the risk of forest fires and affecting the livelihoods of Indigenous communities every year. In 2016 and 2017 large numbers of cacao trees were burned, meaning that income can no longer be generated by communities through selling cacao paste. In 2019 and 2020, fires primarily affected forests of cusi palms, and Indigenous women who had previously earned incomes from gathering the palm fruits and processing them into oil suffered the consequences. Likewise, the most recent fires resulted in the loss of the agroforestry systems of several families, which particularly impacted small-scale banana production. Given that women only manage 5% of farmland used for income generation at the family level, while men manage the remaining 95%, their income is primarily based around gathering, processing and selling forest fruits. They are therefore disproportionately impacted by forest loss.

Conclusions

National agricultural and livestock-related policies in Bolivia are clearly driving forest loss by incentivizing cattle ranching. This has a negative impact on the livelihoods of rural families, and particularly women, because men often emigrate in search of economic opportunities. Women are more vulnerable to the impacts of forest burning and fires, deforestation and forest degradation as they remain in their communities and rely on natural resources for their survival.

At the local level, women also lack ownership of and the rights to the use, access and control of forest resources. This limits their economic options as their livelihoods tend to rely completely on forest resources and small-scale agricultural production. Their limited participation in decision-making over the policies and projects that affect them means that their roles and needs are not taken into account. It is also evident that the problems experienced by rural and Indigenous women in Bolivia are common across the different regions of the country studied.

1 Extensive ranching is carried out on large tracts of land with low production costs because it is done in open fields, a practice that yields low productivity due to the scarcity of forage and water during the dry season (May to October), and because it causes environmental degradation and pressure on native forest resources.

2 The Yungas is a narrow bioregion of tropical broadleaf forest along the eastern slope of the Andes Mountains.

3 Forest vocation lands refers to areas that are only suitable for forestry activities through Forest Management Plans granted by the National Forestry and Land Authority; a change from forest cover to other land uses such as agriculture would cause the loss of vegetation and imminent soil degradation.

4 Private properties sustained by exploitative labor practices, with employees earning little to no wages.

Development banks are failing women

By Merel Van der Mark, Sinergia Animal, Netherlands

World hunger increased in 2020 and so did the gender gap in hunger: the prevalence of food insecurity is 10% higher in women than in men, up from 6% in the previous year. If this trend continues, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal on eradicating world hunger (SDG 2) will not be met, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has warned.

One of the pathways the FAO recommends to address the drivers behind food insecurity is to empower smallholders. While they produce around 70% of the world’s food, they still face hunger and malnutrition. At the same time, the gender gap has to be addressed, as rural women experience poverty, exclusion and the impacts of climate change in a disproportionate way compared to rural men or urban women. Rural women and girls often lack equal access to resources, including access to land and finance, which affects the productivity of female smallholders. Yet, when given equal access to resources, rural women obtain the same yields as rural men and become a driving force against hunger, malnutrition and rural poverty.

Given this reality, one would assume that supporting the implementation of policies that promote the empowerment of rural women, to eradicate hunger and gender inequality (SDG 5), would be at the core of the mission of any development bank. However, the reality is that, while development banks surely pay lip service to the importance of achieving the SDGs, they are pumping billions into large corporate livestock operations. Instead of supporting smallholders, these operations compete with them, concentrating resources instead of distributing them. The largest meat and dairy companies make billions in profit every year.

Even with this being the case, development finance to the industrial animal agriculture sector continues to flow. Marfrig, the world’s second largest beef company based in Brazil, recently applied for a $43 million loan with IDB Invest to “strengthen the sustainability in the beef supply chain”, relying on public investment funds to help deliver its sustainability goals. This application for funds comes soon after Marfrig committed over $1.7 billion in acquisitions of shares in two multinational agribusinesses in a single calendar year. A company with access to millions of dollars to expand their already extensive business has no need of a development bank loan. These lending practices prop up extractive industries like factory farming and favor export markets over local food security, limiting investment in other aspects of the rural economy. Women can be disproportionately burdened by this, as their already reduced access to resources gets trimmed even further when they are squeezed out by big corporate operations.

On top of that, industrial livestock operations cause additional impacts. They often exploit and pollute the land and resources of local communities and strongly contribute to the climate and biodiversity crisis we are facing. The health outcomes have an especially important gender dimension because women are often primary caregivers in the family and responsible for maintaining the household, resulting in innumerable hours of unpaid work. These impacts, which put at stake the future of humanity as a whole, are often strongly felt by rural women who rely on natural resources for their livelihoods and have the least capacity to respond to natural disasters.

Development banks could effectively integrate the SDGs into their model by prioritizing resilient, diversified community-led food production, especially by supporting women-led peasant collectives. Instead of a top-down approach at the mercy of global markets, let women and their communities determine the best seeds, breeds and practices to sustain themselves while preserving their resources, meeting nutritional needs and celebrating culture. Public finance can provide and strengthen access to local and regional markets and more equitable distribution of food. Industrial livestock operations rely on monocultures and imposing a handful of plant and animal species onto non-native environments with resource-intensive inputs and harmful outputs. Community-determined food systems tend to use less resources, which is certainly more compatible with a changing climate.

Instead of funneling billions to some of the largest corporations, development banks should support smallholders, in particular women, because providing them with equal access to education, health care, financial resources, land but also decision power, is key to fighting hunger and poverty.

Ban grazing or give forests to livestock farmers? Nepal’s overgrazing dilemma is

hitting women hardest

By Shova Neupane, Tulasi Devkota, Amika Rajthala and Bhola Bhattarai, National Forum for Advocacy Nepal (NAFAN), Nepal

Livestock farming is a major driver of deforestation and forest degradation in Nepal, due to both overgrazing and the collection of animal feed from forested areas. Nepal’s 2018 REDD+1 national strategy identified overgrazing and uncontrolled grazing as the fourth highest priority of nine drivers of deforestation and forest degradation, and it advocates for restrictions on access to forests for livestock farmers.

At the same time, livestock farming is seen as a valuable poverty alleviation tool, and a route to economic prosperity. In apparent contradiction to the REDD+ strategy, another UN-financed scheme, the Leasehold Forestry and Livestock Programme, has been encouraging smallholder livestock farming in national forests to support livelihoods and restore degraded forests.

These opposing approaches have significantly different impacts on rural women in Nepal, who perform around 70% of the work involved in livestock farming. Women are largely responsible for collecting animal feed, and poorer women tend to be more involved in livestock farming. At the same time, women have limited control over livestock-related finance and decision-making.

Livestock farming in Nepal

Much of the country’s population of almost 23 million ruminant livestock (cattle, buffalo, sheep, and goats) are either grazed openly and/or fed with forage and fodder collected from nearby forests.2 Although statistics on the proportion of animals that are grazed openly in forests is not available, even animals that are kept intensively and stall-fed often derive a considerable amount of feed from local forests, in many cases exceeding their carrying capacity.

Overgrazing is widespread in the Tarai, Siwalik, and high mountain areas of Nepal, however, grazing pressure in the mid-hill forests has been drastically reduced due to the actions of Community Forest User Groups. Grazing in lowland regions is mainly practiced by small-scale sedentary farmers and nomadic herders in the high mountains. Government-managed forests are most affected by overgrazing, as there is no grazing control in these areas. On the other hand, restrictions on livestock grazing and fodder collection—some of them very strict—are in place in community forests,3 leasehold forests,4 and protected areas, and hence they are the least affected by overgrazing.

Whilst these restrictions have reduced pressure on forests in some areas, they have also had negative consequences, particularly on women’s livelihoods, despite the fact that small-scale livestock farmers are often involved in decision-making in community forests. Some Leasehold Forest User Groups (LFUGs) have also chosen to introduce grazing restrictions, although this land tenure system also promotes livestock farming by making land available to farmers to keep livestock on for milk and meat production, as discussed in more detail below.

REDD+ and the intensification of livestock farming in Nepal

A study conducted in 2014 surveyed 324 farmers in Nepal and suggested that REDD5 activities have reduced grazing and forest use for livestock production and caused livestock farming systems to intensify. The study found that farmers with intensive livestock systems have higher incomes, suggesting that the strategy of restricting access to grazing and encouraging intensification has had a disproportionate effect on poorer households. Although it failed to provide gender-disaggregated data on men’s and women’s participation in the different livestock systems, it did show that women have a greater share of responsibility for livestock farming overall, making it likely that poorer women benefited the least from livestock-related REDD policies.

Nepal’s more recent REDD+ strategy appears to follow the path set out by prior UN-REDD work by aiming to support and incentivize small-holders to grow crops to feed livestock in more intensive stall systems, and to promote fodder and forage management in community and private forestry areas, restricting access for grazing and fodder collection. The strategy includes interventions such as promoting multipurpose fodder management, stall feeding, and scaling up fodder reserve systems like silage and hay for use during winter months.

This is consistent with the Forest Act, which seeks to limit grazing and the collection of fodder in forests, and government policies that prioritize intensification and mechanization of livestock production. According to the Department of Livestock Development, the intensification of livestock production is currently being significantly subsidized with public money. For example, the Prime Minister Agriculture Modernization Project subsidizes the purchase of tractors and other agricultural equipment and tools, seeds, and fertilizers. The recipients of this support tend to be larger farms owned by local elites with connections to government officials.

REDD+ in Nepal has also been criticized for not effectively promoting participation by disadvantaged groups, affecting women in particular due to their limited access to public space and capacity to articulate their concerns. Women, forest-dependent poor people and Indigenous People have furthermore been poorly represented in multi-stakeholder forums created to govern the REDD+ process.

The Leasehold Forestry and Livestock Programme

Contrary to UN-supported REDD and REDD+ activities, the Leasehold Forestry and Livestock Programme in Nepal has encouraged smallholder livestock farming in leasehold forestry areas as a strategy to both restore degraded forests and improve the lives and livelihoods of some of the poorest households. The Programme, financed by the UN’s International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), began in 2004 with the aim of reducing poverty in 44,300 poor households that were allocated leasehold forestry plots on long-term leases in 22 mid-hills districts. It aimed to allow households to increase production of forest products and livestock by giving small groups of households organized into Leasehold Forestry User Groups (LFUGs) direct access to forests and rights to use them. Since their livelihoods were dependent on the forests, rural communities would therefore have an incentive to maintain and restore the forests they were allocated.

According to the final report on the program, which finished in 2014, the 21,000 hectares included in the project saw increases in tree and ground cover, an improvement in fodder availability and increases in household income and food security. The program also had significant positive social, economic, and environmental impacts, as well as personal impacts on women. For example, women had to spend less time collecting fodder and fuelwood, saving them two to three hours a day, which they put into income-generating activities. Their increased contribution to household incomes gave them a greater say in spending, as well as participation and decision-making power in the community. Further still, the increase in solidarity and group strength achieved by the project’s capacity-building efforts meant that women were more confident to voice their concerns and fight for their rights in their communities.

It was also observed that the performance of women-only forestry groups was better than that of mixed or men-only groups; they had greater participation in meetings, more savings and investments and their forests were in better condition. Even in mixed groups and men-only groups, it was usually the female members of households who did the forest work, which highlighted the unequal distribution of workloads.

However, while access to resources and decision-making power may have improved for women, these benefits remained largely male-dominated, including profits from livestock farming that were largely generated by women. In many cases, even the loans borrowed in the name of women were managed by their husbands. Similarly, although women saved time collecting forest products, overall they experienced an increase in workload because they were managing leasehold forests on top of their usual responsibilities, although they generated more income.

Livestock farming in Raksirang Rural Municipality

In order to assess the relative merits of the two different approaches to livestock farming and forest conservation in Nepal and their gender-differentiated impacts, NAFAN’s research team visited Raksirang Rural Municipality in Makawanpur district in October 2021. Raksirang was within the Leasehold Forestry and Livestock Programme project area, and its national forests are also covered by the 2018 REDD+ strategy.

There are 162 LFUGs in Raksirang, representing a population of 7,300 people, and they manage 830 hectares of forests. Six key informant interviews were carried out (three with women and three with men), and 16 people participated in two focus group discussions (nine women and three youths). All interviewees and participants were Indigenous. The key informants were the leader of the Nepal Chepang Association, a leader of a LFUG, the leader of Raksirang Rural Municipality, the Secretary of the Ministry of Agriculture, the leader of Devitar farmer’s cooperative and a representative of a newly-formed private livestock farming company. Focus group participants included members of LFUGs, livestock farmers, and members of farmers’ cooperatives. They discussed the strengths, weaknesses, and opportunities of leasehold forestry for livestock farming.

The importance of fodder collection to livelihoods

The interviews highlighted the fact that, in general, LFUGs are unaware of the various forest and livestock policies and programs that cover the region, despite the impacts that they have on their lives. On top of this, the leasehold forestry program has not been successfully implemented. A woman member of a LFUG stated that “We have more than 162 LFUGs in our municipality, but almost all groups have been dysfunctional for the last five years. We are uneducated, without external support we cannot revitalize our groups”. She said the LFUGs do not get the necessary support from Divisional Forest Office and other agencies.

The chairperson of Dharapani LFUG said: “We are in the hilly area. This area is under a leasehold forestry development program implemented by the government but 99% of people in this area do not know about the forest policies and laws. They collect firewood, fodder, leaves, NTFPs [non timber forest products] from the forest for their daily use. In such a situation, how can they protect the forest?” She explained that the villagers are farmers that raise buffalo, goats, and sheep for their livelihoods, and that if collecting fodder is restricted in leasehold forests, they will have no way to feed their animals.

Conflict with the customary rights of Indigenous Peoples

The Indigenous Chepang and Tamang Peoples make up the majority of the population of Raksirang. They depend on agricultural activities for their livelihoods, and have been managing national forest areas for centuries. Traditionally, they practiced shifting cultivation in forest areas, but with the implementation of the Forest Act in 1993 the government banned shifting cultivation and converted the forest management system in Raksirang into leasehold forestry.

The leader of the Nepal Chepang Association argued that in doing so the government weakened the customary rights and practices of the Chepang, with forests now ultimately being controlled by Divisional Forest Office staff at the community level rather than Indigenous groups. It is estimated that more than 60% of families in Raksirang have lost their land rights because of the leasehold forestry program. For the past ten years the Nepal Chepang Association has been advocating for the ban on shifting cultivation to be lifted, but the draft policy they prepared and shared among stakeholders to make this happen has not been supported by the government.

During a focus group discussion, the chairperson of Kalidevi LFUG stated that over the past six or seven years no activities have been conducted in leasehold forestry areas due to the conflict between the Chepang community and the government of Nepal; the Chepang claim the territory under their customary system, but the government has converted the Indigenous land to national forest. This has directly impacted the livelihoods of Indigenous women and girls because they are responsible for feeding and caring for their families, cultivating land, raising livestock, selling produce, and carrying out work in the community such as participating in meetings, engaging in forest conservation activities, and celebrating festivals.

In general, male members of households work outside of their villages in nearby cities and are much less involved in farming and forest-based livelihood activities. The ban on traditional farming practices and insecurity of their land tenure significantly increases the burden on Indigenous women.

A woman member of the Kalidevi LFUG said: “My husband is a laborer, working in Damauli. He earns 600 Nepali rupees [4.40 Euros] per day. He comes home every month. He brings rice, salt, oil, and lentils for us. If he does not earn money from his work, we do not have options. There is no land in our family, our khoriya (customary land) has been converted into national forest. We do not have the right to access the forest or cultivate in it.”

Lack of government support for Indigenous farmers

Despite the significant support available for livestock farming and agricultural intensification in general, Raksirang’s Indigenous farmers are not able to access it. Instead, it is diverted into newly formed private companies with links to the federal, provincial, and local governments that farm on a larger and more intensive scale. There is no publicly available information on how public finance is being spent on livestock farming, but according to a member of the Devitar Farmers’ Cooperative, “women in the cooperative have not been informed about the grants [for livestock farming], and are unaware of the new company registration process too [that is required to receive government support].” A woman farmer from Devitar village in Raksirang also described how it is impossible to get information from the local government and thus very difficult for poor farmers to access public financing.

Conclusion

Conflicting policies and practices around livestock farming and forestry are having wide-ranging impacts in Nepal. On the one hand, the REDD+ strategy and other national-level policies aim to minimize pressure on forests from open grazing and fodder collection, whilst incentivizing intensification such as growing crops specifically as animal fodder and feeding animals indoors. On the other hand, the Leasehold Forestry Programme has handed over small areas of forests to the poorest households so that they can develop forest-based income-generating activities such as livestock farming, and at the same time restore degraded forests. One approach clearly harms rural women, while the other has the potential to significantly benefit them.

However, undermining the leasehold forestry approach and indeed other management practices is the fact that customary land rights have still not been secured for Nepal’s Indigenous Peoples in places such as Raksirang Rural Municipality. Chepang women in particular have lost access to and control over forest resources, and have been banned from carrying out their customary farming practices. Because of this, they have been unable to benefit from the leasehold forestry program, and are more likely to be negatively impacted by further restrictions on livestock farming linked to REDD+.

Nepal’s REDD+ strategy identifies poor coordination between stakeholders, a lack of effective land use policy, and insecure forest tenure as the leading underlying causes of overgrazing. However, these same underlying causes are also structural barriers to achieving gender justice in Nepal, as seen in Raksirang. REDD+ projects must now deliver on their commitment to ensure the “adequate representation of women, poor, indigenous people and socially marginalized groups in key forestry decision-making bodies and processes and recognize the traditional and customary practices of forest management“, to revitalize the traditional knowledge and forest management practices that have protected and conserved forests for generations.

1 Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation and Enhancing Forest Carbon Stocks, a UN program.

2 MOALD. (2021). Statistical information on Nepalese Agriculture. Kathmandu: Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Development (MOALD).

3 Community forestry is a participatory forest management system in Nepal where more than 2.2 million hectares of forests are controlled by over 22,000 Community Forest User Groups (CFGs).

4 Leasehold forests are areas of degraded national forests that have been handed over to poor and marginalized households for up to 40 years to support their income-generating activities. 41,730 hectares of state-owned degraded forest lands have been leased so far to Leasehold Forest User Groups (LFUGs), which are made up of five to 15 of the poorest and most vulnerable households.

5 REDD was the precursor to REDD+.

Georgia’s “gender diet”: How intensive agriculture is destroying rural livelihoods and increasing gender inequality

By Olga Podosenova, Gamarjoba, Georgia

Georgia is known as the homeland of shashlyk (or shish kebab), and so this small Eastern European country has a reputation for eating a lot of meat. However, the facts indicate the opposite – Georgia’s average per capita meat consumption is 26 kg per year, one quarter of the amount of the United States and ranking alongside the poorest African nations, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

Even less meat is on the menu for Georgian women. In 2019, a survey by a group of young feminists called StrongGogo found that more than 80% of women said they eat less meat than their male partners. This difference in diet is rooted in centuries-old Caucasian tradition according to which male soldiers were expected to protect their community and were given the most precious foods. Although living in caves is a thing of the past in Georgia, the gender prejudice that “the meat goes to the strong” lives on. This is despite the fact that everyone should have equal access to food, regardless of gender.

Gender inequality is pervasive in Georgia’s rural communities, where women have greater responsibility for keeping livestock, and spend more time collecting animal fodder and feeding and milking animals. As well as working harder on family farms, rural women are also responsible for cooking, which is usually done over an open fire, exposing them to smoke that is hazardous to their health. Collecting fuelwood for the winter is another burden shouldered by women, which adds to their unequal workload, limiting their opportunities.

Livestock farming in Georgia currently takes place mainly on private small-scale farms, which produce predominantly high-quality and organic animal products. However, the country still struggles with food security, because the meat that Georgian farmers produce is mostly exported to Azerbaijan, Iran and Turkey. Meanwhile, most of the country’s inhabitants eat frozen meat imported from countries such as Brazil. According to Geostat, Brazilian meat accounts for 82.5% of pork imports, 26.7% of beef imports and 20.9% of poultry imports. Negotiations are also underway to increase imports of frozen meat products from Uruguay, and at the same time to export more meat to Turkey. Even meat industry sources blame Georgia’s meat exports, which tend to be “live” exports that fetch a higher price, for meat shortages and rising local prices in Georgia.

To encourage economic growth, Georgia’s government is throwing its weight behind a model of intensive agriculture by supporting the creation of large farms and the use of chemical inputs. Policy support for intensive livestock production will only increase gender inequities and exacerbate the exploitation of rural areas.

Through projects financed by the World Bank and other international development banks, the Ministry of Agriculture has set a goal of doubling the area of agricultural land over the next ten years. Although the environment is described as a priority, this plan will harm wild and natural areas, including vulnerable mountain ecosystems. Small-scale farmers also believe that it will aggravate unequal access to healthy food.

The development model described above clearly has nothing to do with justice and is not the best option for the economic well-being or health of Georgia’s citizens. Increasing production and profits will rely on the exploitation of the local workforce, whilst herds of sheep — Georgia’s biggest livestock export — trample unique mountain meadows and cause deforestation. At the same time, rural farmers remain in a difficult economic situation and are held hostage to fluctuations in international meat markets.

On the other hand, the seeds of agro-ecological farms have already been sown in the South Caucasus. These farms, such as Ecovillage Georgia, are usually initiated by women, and they have the potential to lead the way to truly sustainable and equitable food production. Georgian NGOs, including Gamarjoba, StrongGogo and the Greens of Georgia, are promoting demonstration projects of environmentally friendly organic farming solutions, installing renewable technologies and creating agricultural and energy cooperatives. All of these contribute to achieving gender justice and improving the lives of rural women. For example, energy cooperatives supported by local NGOs help rural women to install solar water heaters, which reduces the need for traditional wood-burning stoves, reduces health impacts, frees up their time and prevents tree felling. Installing solar ovens for cooking has a similar impact.

In Georgia, there is a saying that goes, “A Georgian woman can feed her family by laying a table of herbs collected in her garden.” Georgian women’s traditional knowledge and agroecological approaches can therefore improve equitable access to resources, local food sovereignty, climate-friendly livestock production and the preservation of Georgia’s unique mountain ecosystems.

In search of tekoporá: Gender considerations in industrial livestock farming in Paraguay

By Miguel Lovera, Iniciativa Amotocodie

Unsustainable livestock production in Paraguay occupies a large part of the national territory and the majority of its most fertile land. An estimated 94% of the country’s cultivated land is used to grow export crops, while only 6% is used for crops grown to meet domestic demand, such as food and raw materials for local handicrafts and industries. This economic model is disastrous for the environment and people, especially for women, who have less access to essential goods and services and receive considerably lower pay than their male counterparts for the same work.

Undoubtedly, deforestation is the most devastating environmental and socioeconomic activity in Paraguay. Forest ecosystems have been eliminated largely to make way for agriculture and cattle farming, to accommodate extensive farms which are gradually intensifying with the explosion of a model of mechanized agribusiness controlled by large agricultural corporations. Paraguay’s Upper Paraná Atlantic Forest, a humid subtropical formation of great biodiversity, has been almost totally eliminated, much like other types of forests in the eastern part of the country. The Chaco region, which includes western Paraguay, currently has one of the world’s fastest rates of deforestation. According to monitoring by Güyra Paraguay, for the period from January to October 2017, the Gran Chaco (in Paraguay, Argentina and Bolivia) had an average forest loss of around 1,000 ha/day, with over 60% taking place in Paraguay.

The main causes of the destruction of ecosystems in the Chaco, including both deforestation and forest fragmentation, are cattle ranching, road building, and hydrocarbon prospecting. This process of destruction increased sharply in 2007 with the opening of international markets for beef, expanding from the Central Chaco to the North.

The impact of deforestation is particularly severe for women, who are normally responsible for providing for the household and ensuring proper nutrition, health, and water supplies. For Indigenous communities, the scarcity of forest resources represents a major obstacle to women’s development and tasks they traditionally carry out, such as tending to chacras (small farms) or the use of forest resources for medicinal purposes.

Policies and programs aimed at addressing the ramifications of this economic model pay scant attention to the needs of women, which compounds the discrimination and marginalization they already suffer in Paraguayan society.

Methodology

This article analyzes, from a gender perspective, efforts to address the problem of agriculture and cattle ranching in Paraguay by various actors. It also includes peasant and Indigenous women’s vision, strategies and proposed solutions to the differentiated impacts of these efforts.

The research process involved reviewing secondary sources and interviewing 14 women leaders from different ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds. These interviews were held with the discretion needed to guarantee freedom of expression in the context of a society that still does not tolerate or correctly interpret demands for women’s equality, which are necessary for the full enjoyment of their human rights.

Unsustainable livestock production

Paraguay has the most unequal distribution of land on the planet. Cattle ranching and soybean monoculture are currently the largest sectors of production, and Paraguay has almost 14 million head of cattle, or two animals per human inhabitant. Some 2.5 million cattle are slaughtered per year and beef exports are around 380,000 tons, roughly double the amount sold domestically. The livestock sector uses some 26.2 million hectares of land, of which 5.6 million hectares are cultivated pastures, 10.6 million hectares are natural pastures and 10 million hectares are native forests. Meanwhile, 90% of cattle ranchers have herds of less than 100 head of cattle, while the other 10% own 82% of the national herd. This concentration becomes even more pronounced if we look at larger ranchers with herds of over 1,000 head, in which case, 2% own 54% of the herd.

The consequences of this model are both environmental and social. Paraguay is the most vulnerable to climate change of any country in South America and is among the countries in the region facing the most extreme risks due to the climate crisis. It also has some of the continent’s highest rates of poverty and inequality, with a below average Human Development Index.

Inequalities also extend to the arena of gender, with significant gaps noted by multilateral institutions such as the World Economic Forum, including economic disadvantages and gender violence, a situation that worsened during the pandemic.

The gender gap in access to land is considerable; only 15% of land is controlled by women. On top of this, rural, peasant and Indigenous women face different forms of violence deployed with State backing at the hands of agribusiness, real estate companies, and even organized crime, with the involvement of military and paramilitary forces.

Livestock activities are carried out on the foundation of this structure of land and distribution. Women clearly have less participation and are subordinate in their relationships with men, facing discrimination because of their gender and socioeconomic status. Women, however, contribute disproportionately to food production and household maintenance, child rearing and care of the elderly and infirm. This contribution, neglected in formal accounts, represents a formidable portion of the household economy, especially in rural areas.

Women are deeply affected by the extensive livestock production model. The big livestock operations in the Chaco rely on the labor of Indigenous men, who must move to the ranches, sometimes hundreds of kilometers away from their communities, which disrupts community and family life. Due to men’s absence, many Indigenous women must take responsibility for obtaining food, whether purchased or hunted and gathered locally, leaving them unable to participate in traditional educational processes and native cultural activities necessary to maintain their way of life.

Measures aiming to tackle deforestation in Paraguay

A handful of actions and policies exist in Paraguay that are designed to tackle the impacts of unsustainable livestock production, always linked to the country’s international commitments and the influence of international cooperation. However, the measures that have been adopted do not truly consider gender and are mainly based on the application of extractive practices that reinforces the agro-industrial model.

Such is the case of livestock production in “agroforestry” plots that combine the planting of exotic pastures alongside exotic trees – mainly eucalyptus – on peasant land. This strategy, in fact, increases the area occupied by agribusiness and decreases the ability of women to gain access to land.

The incorporation of peasant plots into these schemes entails the annexation of peasant land by agribusiness, as the latter is the potential recipient of most of the future timber harvest (used for drying grain). Thus, it is difficult for peasants to oppose the expansion of these tree plantation operations, since they will be directly involved in the business, contributing their land and labor to the provision of a raw material that is (so far) indispensable to agribusiness.

Several policies and regulations are driving the increase of forest plantations in Paraguay, such as PROEZA (Poverty, Reforestation, Energy and Climate Change), a program aimed at introducing eucalyptus production on peasant farms and Indigenous territories. It is financed by the Green Climate Fund (GCF) and also receives support from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization. Its documentation mentions “gender vulnerability,” but the project promotes the dominant patriarchal model meaning that gender-differentiated impacts are compounded.

National policies include Law 536 on the Promotion of Forestation and Reforestation, which reimburses up to 75% of the cost of the implementation of forest plantations, and Law 3.001/06 on the Valuation and Remuneration of Environmental Services, which adds forestry to the activities eligible for compensation. The country also has a remarkable level of deregulation and entrepreneurial “freedom” that favors the private sector. In November, the Rural Association of Paraguay (ARP, in Spanish) organized a seminar praising the government’s policy of “no regulation.”

An example of existing mitigation measures is the National Platform for Green Commodities. The fact that the original name in Spanish uses the English-language term “commodities” demonstrates the Western corporate bias in the jargon used by agents of the agribusiness model within international cooperation. Activities that have taken place under this framework include meetings designed to introduce women to soybean and meat production. However, agricultural production in the country is based on large-scale monocultures and large landed estates or latifundios, the patriarchal land use model.

According to participants in events organized by the National Platform of Sustainable Commodities, the main objective is to promote the expansion of agro-industrial livestock production, while the sustainability component is minimal even though the process is presented as the sustainable alternative to the prevailing model. The references to “sustainability” are not accompanied by an attempt to address the problem of the impacts of deforestation, or of the proposed development model on water, soils or biodiversity.

The narrative is that soy supposedly would not contribute to deforestation in the Chaco. They say that biodiversity is increasing in the central Chaco, and that around 500,000 ha could be sown without felling a single tree. This logic rationalizes the increasing exploitation of the Chaco by the same productive, socioeconomic and gender-blind approach that has made Paraguay one of the poorest countries on the continent.

Paraguay presented its updated Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) to reducing emissions under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in April 2021. Despite being more than 90% dependent on reducing deforestation, it did not include measures for recovering land and territories that have been usurped, nor measures to recover territorial management by Indigenous and peasant communities, nor penalties for deforestation. It did not even attempt to reign in agricultural and livestock production, which depends entirely on deforestation for its expansion.The update was designed to make the country “more competitive” economically, and describes good intentions and general aims that do not match the reality of national policy that encourages deforestation and the advance of agroindustry with grave consequences.

Genuine proposals made by those most affected by the agroindustrial model

Indigenous and peasant communities have developed strategies of resistance and struggle to confront the state’s prioritization of private interests over the common good, and the gender injustices that this causes.

Ayoreo women and their fight for biodiversity

The Ayoreo People in Paraguay today occupy just 2% of their original territory of about 110,000 km2, which has caused a major transformation in their subsistence and cultural practices. Areas around the Ayoreo communities have been heavily transformed, converted into pastures for livestock, and no longer contain habitats for local flora and fauna, and their capacity for primary production has been drastically reduced.

Women’s relationships with the environment, and particularly with forests, are very important. For the Ayoreo, the forest is the world; it is their habitat and their cosmos. Its destruction is a significant blow to the culture and cosmovision of the people, and particularly women, whose ability to adapt or recover the land is limited since it has been usurped by powerful sectors that are reluctant to give it up.

Ayoreo women frequently spend time gathering caraguatá (Bromelia sp.) to weave traditional textiles. This species has been reduced due to deforestation, and the plants that remain are located far away from the Indigenous communities, which means that women must spend additional time and resources traveling to obtain it.

Women leaders have worked to regrow caraguatá through enrichment planting in forest areas, a process that has yielded good results from the point of view of forest restoration and resources. These initiatives help provide raw materials to the communities, but do not solve the serious problem of lack of land faced by the Ayoreo.

Peasant voices

Perla Álvarez is a prominent figure in the peasant movement in Paraguay. A feminist activist and environmentalist, she explains her strategic vision for the peasantry based around the organization Vía Campesina to confront the threats of environmental destruction due to the imposition of agribusiness.

“We women do not use the word conservation; we speak of rootedness, of non-displacement… We even talk about the need to protect what we have, along with conquering new territories. If we decide we want to stay in the countryside, to keep ourselves there. That includes protecting all of the natural goods that we have: water, forests, seeds, the land where we produce [food], and where we live, that’s why we talk about our territories, and our relationships too, that’s why we talk about our ways of being in the countryside. Being in the forest, in the countryside, outside of the city, implies other ways of relating to humans and nature.

“When we talk about conservation, we talk about rootedness, staying in the countryside, recovering our roots–this includes biodiversity. For example, we talk about how it’s not the same to have just two varieties of corn, because most families today keep just two varieties and that’s it, when ten years ago, most families had at least six or seven varieties, because that radically reduces the quality of nutrition, and not just human nutrition, but even the ability to raise a diversity of birds, because there are varieties of corn that are used to feed certain animals.

“That is our struggle, the defense of teko, of tekoha, of tekove. Tekoha is the territory, the physical, material place where we practice our culture, or teko. It is the place where one lives, where one is, where one produces and where people reproduce. Tekove is life… ñande rekove ñande rekohape (we live in our territory). And in that tekoha we aspire to tekoporá, which is total wellbeing, the culture of wellbeing, wellbeing understood in the sense that one feels comfortable, good, satisfied, or happy. That is tekoporá, the full enjoyment of rights, of environmental wellbeing, of health, [wellbeing] in one’s relationships; when one is doing badly, they lack tekoporá. Tekoporá is the human aspiration that we work towards. And to have tekoporá, you need tekokatu, which is dignity, one what achieves through dignified work.”

Conclusion: Prioritizing profit over justice

Women are underrepresented and marginalized in Paraguay and are disproportionately exposed to many forms of violence, particularly in rural areas. However, they have organized and resisted the advance of a system whose forms of expropriation have intensified during the COVID-19 pandemic. The networks of care that they have woven in times of acute socioeconomic, health and environmental crises are essential, especially in the countryside, where there have been increased hostilities by large landowners and companies seeking to grab land through the use of violence.

Unsustainable livestock production, which prioritizes profit, will not be able to consider, much less respect or remedy the numerous cases of violation of women’s rights and neglect that occur in the country. The levels of deforestation and destruction of ecosystems have reached a tipping point in almost all ecosystems throughout the country. Meanwhile, the policies and processes aimed at addressing this problem are subordinated to powerful interests motivated by profit and to a government that is enlisted as an agent of these processes of economic expansion.

Thus, the policies created to address the pitfalls of the development model resort to the same aberrations that justify their origins. In reality, they simply worsen the situation of expropriation of land and production, ignoring the problems of the majority of Paraguayan society and without the gender approach needed to ensure justice.

Women and agroecology in Latin America: Voices from the ground1

By Mora Laiño and Lucía Moreno, LATFEM, Argentina

The current agri-food system is characterized by intensive cultivation practices that degrade soils and cause record deforestation, including genetically modified monocultures designed to tolerate agrochemicals that harm people and the environment, the concentration of wealth in the hands of corporations, and inequities regarding access to land.

There is an urgent need to revive and develop more sustainable food production methods hand in hand with historically marginalized groups who do essential work, such as women, who have historically played key roles in gathering seeds, preparing soils, raising animals, forging community networks, harvesting and storing crops, and selling foods.

Despite being the main producers of food, women face barriers in accessing land, productive and financial resources, technology and education, in addition to shouldering the majority of the burden of unpaid domestic and care work. In Latin America and the Caribbean, women own just 18% of agricultural lands and receive 10% of the credit and 5% of the technical assistance granted to the sector.

In response to these inequities, peasant and Indigenous women are organizing to produce food using agroecological methods. Their common objective is to create agri-food systems that are socially, economically, and environmentally just. They are seeking to reconnect with their land, knowledge, seeds, and history through the political act of working the land and producing food.

Zaida Rocabado Arenas and Maritsa Puma Rocabado of the Land Workers’ Union (UTT) in Argentina explain: “With agroecology, we feel safe and peaceful taking care of nature, the countryside, and our families.”

As well as producing healthy foods and taking care of the environment, they seek to make visible the multiple inequalities that exist.

“We women have been historically excluded from social participation. Our experiences of living in the countryside help us to identify the forms of oppression and their origin,” says Viviana Catrileo of the National Association of Rural and Indigenous Women (ANAMURI) in Chile.

“With agroecology, our work as peasant women is politicized and valued, because it’s not a recipe but a political movement,” says Alicia Amarilla of Paraguay’s National Coordinating Committee of Rural and Indigenous Women (CONAMURI).

These powerful voices are being asserted throughout the region, demonstrating the importance of collective organization and political training as tools of struggle. The message is unequivocal: a transformative solution must alter the patriarchal structure in rural areas and involve systems of production based on greater inclusion and equality.

Sofía Sánchez of Argentina’s National Peasant and Indigenous Movement (MNCI-UST) says: “The solution is a collective one, based on community, work, and care for the land. I hope that one day we will have in our hands a market for artisanal and peasant products that construct a new economy: [one that is] feminist, peasant, Indigenous, and of the people.”

1 A longer version of this article was originally published in LATFEM.

A feminist perspective on recent efforts to decouple livestock farming from deforestation

By Caroline Wimberly, livestock expert, United States, and Simone Lovera, GFC, Paraguay

In the build-up to, during and immediately after COP26 in Glasgow there was a rush of initiatives announced by the UN, governments and the private sector to address deforestation linked to meat production. However, none of them attempt to reduce the production and consumption of animal products, and most treat gender as an afterthought, if at all. In this context, can they contribute to gender justice, or do they simply compound gender-differentiated impacts?

As unsustainable cattle ranching and soy production are amongst the four main drivers of forest loss, this edition of Forest Cover features several case studies highlighting how forest loss and unsustainable livestock production specifically burden women and girls. But that does not mean that policies and projects to mitigate the impacts of unsustainable livestock and feedstock farming on forests will automatically benefit women.

For example, shifting genetically-modified (GM) soy production out of forest zones and into areas inhabited by peasant communities could increase breast cancer rates linked to the heavy use of agrochemicals. It could also lead to a concentration of land ownership and rural depopulation, as the practices of soy farming and cattle ranching are particularly labor extensive.

Women are the first to suffer as they are left without access to schools, health centers and other public services that they and their families require. Moreover, “solutions” to halting deforestation rarely grapple with biodiversity, animal welfare, human health, methane emissions or other consequences of unsustainable livestock farming.

Pledges and policies to address commodity-driven deforestation tend to fall into three broad categories: public-private partnerships (PPPs) between UN agencies, corporations and other actors that promote commodity production that causes less deforestation; voluntary private-sector led schemes; and legislative initiatives to oblige corporations to practice due diligence for imported commodities that are associated with deforestation and/or human rights violations, such as has recently happened in the UK, US, France and Germany.