A new report on the proposed ‘Tropical Forest Forever Facility’ by the Global Forest Coalition and Fundación Solón

English / Português / Español / Bahasa / Français

This report offers an in-depth analysis of what we currently know about a market mechanism aimed at forests called TFFF (Tropical Forest Finance Facility) that is said to be launching this year around the 30th UN Climate Convention (COP30) in Brazil. Tropical forests are essential ecosystems, and gravely threatened by the same logic of extractivism and endless pursuit of profit that now is being applied to their “protection” at an international level, whereby investors would seek monetary returns on these ecosystems based on a commercial valuation of the “services” they provide.

How would the TFFF work? Who would invest in it, and who would back it? How much money would be distributed, and how? What is the role for forest peoples? What happens if it fails? There is also the question of the valuation of forests; are tropical forests that remain standing in Brazil, the Congo, and Indonesia really worth $4 per hectare?

These are just some of the questions surrounding the TFFF, a false solution to forest loss which we can expect to hear a lot about this year. It’s time to get informed and prepare for a crucial debate on this topic with major implications for Indigenous Peoples and local communities, forest peoples, environmental defenders, women, and all those who appreciate the inherent value of the world’s tropical forests.

Learn all about the TFFF in our new report, available in Spanish and English (forthcoming in French, Portuguese, Bahasa, and more). Download the report and share it with others.

CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD THE REPORT:

TFFF: A False Solution for Tropical Forests

By Mary Louise Malig and Pablo Solón

The Brazilian government is hosting the upcoming 30th Conference of Parties to the UN Climate Convention (COP 30) in Belém do Pará in November 2025, where it plans to launch the Tropical Forest Finance Facility (TFFF).

This initiative bringing together the countries with the most rainforests was facilitated on the sidelines of the G20 summit in Indonesia in November of 2022. An agreement was announced between Brazil, Indonesia, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which combined have an estimated 52% of the world’s rainforests.

Three countries signed an agreement on the sidelines of the G20 Summit in Bali in November 2022. Photo: Brazzaville Foundation.

The mechanism was conceived more than 15 years ago by a senior executive at the World Bank named Kenneth Lay. In 2018, the Center for Global Development circulated a proposal for this financial mechanism [1], and the Brazilian government adopted it and presented it at COP 28 in Dubai. Since then, a team of representatives from the Brazilian government, the World Bank, Lion’s Head Global Partners, and others has been working on a detailed proposal that maintains the TFFF acronym, but with a new meaning for one “F”: it is now known as the Tropical Forest Forever Facility.

As of March 2025, the team has produced two concept notes on TFFF. The first, which we will refer to as Version 1, was released on July 5th, 2024. [2] The second, Version 2, was released on February 24th, 2025. [3] There are many differences between the two versions, which we will discuss here. For example, in Version 2, Brazil established an Interim Steering Committee comprised of six tropical forest countries (Brazil, Colombia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ghana, Indonesia, and Malaysia) and six potential TFFF sponsoring countries (France, Germany, Norway, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, and the United States).

Will $4 Per Hectare Correct a Market Failure?

According to the TFFF concept note of July 5, 2024:

“By valuing standing and restored tropical forests, the facility (TFFF) will help address a current market failure by giving a value to the ecosystem services that those forests provide. These include carbon sequestration, water management, biodiversity preservation, soil protection, nutrient cycling, continental and global climate regulation, and climate resilience. Correcting these market failures will reduce poverty and advance economic development, both in forest countries and globally.” (Version 1)

The TFFF is informed by the logic of green capitalism, which assigns a monetary value to ecosystem services, purportedly to conserve them and prevent their deterioration and loss. According to this view, what is free is unlikely to be cared for, so if an ecosystem service is assigned a price, it can attract capital that wants to maintain and profit from that service. Trees have already been commodified for their material aspects such as wood, fruits, roots, or fronds. In contrast, ecosystem services are about the intangible part of the tree; its ability to produce oxygen, store carbon, release water vapor into the atmosphere, serve as a habitat for animals and insects, control erosion, provide shade, and other environmental functions.

For green capitalism, or “the green economy,” the climate crisis is not a product of the voracious logic of profit accumulation, but rather the failure of the capitalist market to assign a monetary value to environmental services and hence attract capital investment.

The premise of the TFFF is, of course, that forests are valuable. However, the whole discussion about the commercial valuation of ecosystem services collapses with the suggestion in TFFF concept notes that the market failure could be corrected by paying $4 per hectare of standing forest. A mere $4 for all the environmental services of a hectare of forest? As we saw above, the environmental services of forests include “carbon sequestration, water management, biodiversity preservation, soil protection, nutrient cycling, continental and global climate regulation, and climate resilience.” These are enormous and essential functions.

So where did the calculation come from? The truth is that the proposed figure of $4 per hectare is the result of an estimate of the potential return of a multilateral investment fund and not an attempt—however failed or impossible—to put a price on forest ecosystem services. [4]

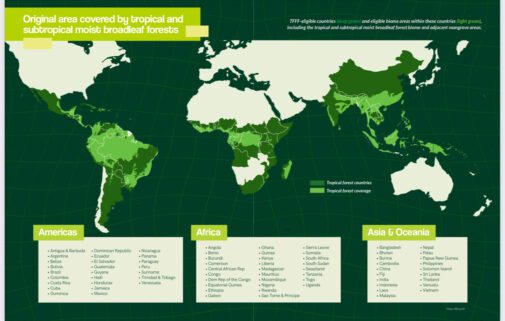

The TFFF would pay investors $4 per hectare annually for one billion hectares of tropical forest spread across 72 countries, according to the list contained in Version 2. Version 1 of the concept note included 67 low- or middle-income tropical forest countries according to the World Bank Group’s International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD). In contrast, Version 2 lists China, for example, an upper-middle-income country according to the IBRD. On the other hand, Version 2 expands the definition to countries located within the limits of the tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forest biomes and adjacent mangrove areas, which includes nations like Argentina.

Original area covered by tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests

TFFF-eligible countries (light gray) and eligible biome areas within these countries (green), including the tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forest biome and adjacent mangrove areas.

To pay $4 per hectare for 1 billion hectares of standing tropical forest, the investment fund would need to generate an annual disposable income of $4 billion.

How Will the TFFF Raise $4 Billion Annually?

According to both TFFF concept notes, to generate $4 billion annually, the fund would need to raise and invest $125 billion. Version 1 states that $125 billion at an annual rate of return of 7.5% would generate $9.375 billion. Of this amount, approximately $5.375 billion would be paid to public and private investors, and $4 billion would be distributed among countries based on the area of their standing tropical forests and discounting certain penalties for deforestation that may have occurred. Version 2 claims that only $3.4 billion would be raised annually, but that $4 per standing hectare would still be paid due to current levels of deforestation, which would result in various penalty discounts.

In other words, the TFFF would operate on the same logic as banks, borrowing money at low interest rates and lending it at higher ones to make a profit. The TFFF would lend $125 billion at an annual interest rate of 4.4% (4.9% in Version 2) and make various investments to obtain an average return of 7.5% (7.6% in Version 2), leaving it with a 3.1% profit on its capital (2.7% in Version 2), which it would distribute among tropical forest countries.

The concept note clarifies that the $125 billion would be primarily loans, not grants.

“The TFFF does not rely on donor grants, subject to the whims of new regimes or the changing priorities of wealthy countries’ budget, but rather by providing a strong value proposition to sponsor investors, generating competitive market returns.” (Version 2)

One of the architects of the TFFF, Garo Batmanian, the director of Brazil’s forestry service, reinforced this idea, saying “What we are asking for is investments.”

There would be two classes of investors in the TFFF:

- Sponsors would be high-income countries, multilateral organizations such as the World Bank, international NGOs, and philanthropic organizations, who would make a one-time, fully repayable investment. Some could also make grants or concessional loans.

- Market investors would be recruited from debt capital markets through the issuance of highly rated, long-term bonds for those seeking a slightly higher rate of return than government bonds from countries like the United States.

TFFF ”sponsors” would contribute 20% of the $125 billion, and would leverage the remaining 80% from “market investors.” The former would invest $25 billion, and the latter $100 billion. These investments would be repaid in 20, 30, or 40 years, depending on the terms of the securities acquired by the different types of public and private investors.

So far, it is unclear which countries would lend to the TFFF—and under what conditions—to reach the first $25 billion or 20% of the fund.

“If the target of USD 25 billions of committed sponsor capital is not achieved upfront, the TFFF would proportionally reduce the payment value per hectare in the early years and seek to continue fundraising until the funding target is achieved.” (Version 1)

Nor are the $100 billion investments from “market investors” guaranteed. It’s all a house of cards, and meanwhile, forest fires and deforestation are ravaging three and a half million hectares of tropical forest each year.

Is $4 Billion Annually Guaranteed?

Both versions of the TFFF acknowledge that if less than $125 billion is raised or if the rate of return is less than 7.5%, the payment per hectare could be less than $4 or could be “temporarily” suspended. This confirms that payment for standing forests is not a response to their importance but rather a financial game typical of any capitalist bank.

During the UN Biodiversity Conference in Cali (COP 16), Colombian former Environment Minister Susana Mohammad expressed support for the TFFF, noting that “what resource-rich countries want is a sufficient, predictable, and consistent flow of funds to public institutions so we can strengthen ecosystem governance.” [5] Is $4 per hectare sufficient, predictable, and consistent? Version 1 of the TFFF notes that “as TFFF is an investment fund its returns cannot be guaranteed.” It goes on to state:

“By buying long-dated assets TFFF will secure a predictable income flow but is subject to reinvestment risk and mark-to-market volatility on its asset portfolio. In the event that the market value drops below certain key thresholds it may be necessary to reduce the rate of payout to TFNs. However historical precedent shows that this would only occur in exceptional circumstances.” (Version 1)

The financiers and bankers behind the TFFF are unaware that precisely because of the worsening climate crisis, the crisis of capitalism, and imperial geopolitical disputes, “exceptional circumstances” are becoming the new normal. In all their risk analyses, they conclude that any problems will be temporary and manageable.

Both versions of the concept note admit that everything could end in an “orderly liquidation” of the mechanism:

“In the event of a permanent depletion in the asset value of the TFFF, TFFF would reduce current and future payments per hectare so as to restore the TFFF to financial sustainability. This could result in a period of lapsed payments to qualifying TFNs. If TFFF were to no longer be rated investment grade, it would seek to commence an orderly liquidation.” (Version 1)

A New Carbon Market?

The TFFF mechanism would not generate carbon or biodiversity credits, nor would it allow for offsets or compensations such as carbon credits, which are permits to continue polluting in one location by purchasing certified emissions reductions elsewhere. The TFFF would be different from but complementary to REDD+ carbon markets. While REDD+ would account for the tons of carbon supposedly reduced, the TFFF seeks to reward each hectare of standing forest.

Both versions of the TFFF argue that forests are underfunded globally through REDD+ compared to the value of the ecosystem services they provide.

“The scale of REDD+ support to date has been vastly insufficient compared to the need. Only 3% of international climate finance supports forests, even though forests have the potential to provide up to 30% of the mitigation needed to meet global climate objectives.” (Version 1)

In this sense, the TFFF aims to better “value” ecosystem services and avoid the complications that REDD+ projects face related to “additionality, leakage, and permanence” of emissions reductions from reduced deforestation. The TFFF claims to be a mechanism “to support the full range of less-marketable tropical forest ecosystem services” (Version 1).

Although the TFFF would not generate market-tradable carbon credits, the mechanism could be used to greenwash companies that invest in it:

“Investors in TFFF bonds will not be able to count an investment as an offset for any carbon linked scheme, but the TFFF would report on its impact and as a participant in the TFFF capital stack, Market borrowing investors would be able to attribute the impact of their investments in terms of carbon captured or avoided production of CO2 as well as Biodiversity protected.” (Version 1)

According to both TFFF concept notes, countries that accept the challenge of this mechanism will be motivated to seek REDD+ resources to achieve their goals and meet their objectives, which will allow the TFFF to “supercharge” REDD+.

Concerns about “double payments” through the TFFF and REDD+ have likely been a major concern for potential TFFF sponsors, and hence Version 2 has an annex dedicated exclusively to this topic.

States Before Indigenous Peoples

Both TFFF concept notes state that payments of $4 per hectare of standing forest would be disbursed to the finance ministries of participating countries.

“Sovereign decision-making: each recipient government will be free to make its own decision on internal allocation of resources received from the Facility, rather than the Facility dictating a universal rule.” (Version 1)

“The TFFF does not determine how tropical forest countries will use the funds awarded to them.” (Version 2)

The rationale for this approach is developed in a box in Version 1 that quotes the Center for Global Development:

“Cash-on-delivery (COD) aid differs from other programs in that it eschews the imposition of pre-conditions and does not require agreements between funders and recipients on strategies to achieve results. The only ‘preconditions’ relevant to COD aid are a good measure of progress and a credible way to verify it. One of the key features of COD aid is that the funder embraces a hands-off approach, emphasizing country ownership and the power of incentives to drive outcomes, rather than financing projects that provide guidance or technical assistance. Under the COD aid model, at no point does the funder specify or monitor inputs. Similarly, the funder does not impose conditions or restrictions on the use of funds (rewards payments). It provides recipient countries with full authority and flexibility to undertake interventions or address policy issues that will lead to the desired results, even if such interventions and policies are outside the domain of the relevant sector ministry or subnational government entity.” (Version 1)

Regarding payment or financing issued to local actors directly involved in keeping forests intact, such as “local governments, businesses, individual landowners, indigenous communities, etc.”, Version 1 states that each recipient country would commit to “either allocate directly, or through some kind of localized funding mechanism” a portion of the funds received.

“The TFFF will make annual payments to the Ministries of Finance of the TNFs. It is proposed that a certain minimum percentage [to be agreed] should be allocated directly to those who effectively conserve forests, such as local communities and protected area managers…” (Version 1)

Version 2 sets this rate at 20% for Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities. Some parts of the document say 20%, while others cite a minimum of 20%. This means that, of the $4 per hectare of standing forest that each country would receive, 80 cents would be paid directly or issued through a funding mechanism established for Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities. The concept note does not specify what would happen in countries that do not recognize the existence of Indigenous Peoples within their national borders, such as China, or countries that apply the recognition of Indigenous Peoples’ rights discretionarily.

This latest concept note states that Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities own or manage 54% of the world’s remaining intact forests. The other actors on the ground are referred to as Forest “stewards,” without breaking them down, as the first version did, into “local governments, businesses, individual landowners…” For these “stewards,” Version 2 does not establish the percentage of the $4 per hectare they should receive. It only states: “Countries are encouraged to allocate the remaining funding to forest stewards, those that directly contribute to keeping forests conserved.”

A portion of the money tropical forest countries would receive would have to be used to establish and/or pay for a “transparent, standardized and reliable method of measuring native forest cover, which could be its own country’s system or that of third parties.”

“Satellite observation will be the primary mode for performance monitoring. It is proposed that the TFFF will set minimum, globally standardized technical parameters for the national country forest cover monitoring system to be considered credible and transparent (ex.: resolution, treatment of clouds, frequency, means of publicizing the information).” (Version 1)

In short, we are faced with a mechanism designed to finance national governments rather than the actors actually involved in forest preservation. On top of this is the question of what it means for forests to “remain intact.” Will Indigenous communities be able to use timber or carry out small clearings to ensure their subsistence? In a broader sense, we might ask: is the TFFF strategy essentially conservationist, or is it an approach based on coexistence with the forest, as is the practice of Indigenous Peoples?

Who Is Responsible for the Debt?

Neither of the TFFF concept notes clarifies where and how the loans from sponsoring countries and bonds issued to market investors will be recorded. Who is the debtor? Who will investors sue if they fail to get their interest and capital back, the TFFF or beneficiary countries? Who will be liable in the event of bankruptcy? Or would public and private investors make risky investments in which, if there is a return, they receive their capital back with interest, and if things go wrong, they lose everything? If the latter is the case, it is not explicitly stated. This raises the question of whether the foreign debt of tropical forest countries would increase, since Version 1 states: “In its simplest format each country would have an ownership equivalent to its standing forest as a percentage of the global standing forest.”

Who Has Decision-Making Power?

Two independent governance structures would exist under the TFFF umbrella, according to Version 2: the Investment Fund and the benefit-sharing mechanism. The first is called the Tropical Forest Investment Fund (TFIF) and the second the Facility.

The Investment Fund would be responsible for managing the loans and bonds of public and private investors, investing $125 billion in capital, and after deducting all expenses (interest, repayment of capital from year 10 onward, and operating costs), delivering the profits to the Facility for distribution.

The Facility would determine which countries qualify for membership in the mechanism, monitor forest cover, issue penalties for deforestation, and pay governments $4 per hectare of standing forest.

Each body would have a separate, independent board of directors. The Facility’s board would be composed of 18 members: nine from the fund’s sponsoring countries and nine from tropical forest countries. Each sponsoring country contributing more than 11% of the initial $25 billion would have a seat on the board. Tropical forest countries in the Americas, Africa, and Asia would have three representatives from each region: one from the country with the most tropical forests in each region (Brazil, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Indonesia), one from the country with the lowest levels of deforestation in each region, and another elected on a rotating basis.

The Investment Fund’s board of directors would be made up of experienced professionals appointed by sponsoring countries based on the recommendations of an independent committee. Board members would receive financial compensation, although their positions would not be full-time.

Both the Investment Fund and the Facility would share a common secretariat and a common trustee, which would be a Multilateral Development Bank, most likely the World Bank.

TFFF and the Baku to Belem Roadmap

Climate finance is one of the most controversial issues in the climate negotiations, surpassed only by the low ambition of industrialized countries’ emissions reduction commitments.

At COP 15 in Copenhagen in 2009, developed countries pledged to raise $100 billion annually until 2020 to help developing countries address climate change. This promise of “increased, new, additional, adequate, and predictable financial support” was included in the earlier Cancún Agreement under the term “mobilizing and providing” $100 billion annually up to 2020. This meant that developed countries did not commit to providing all of these funds, but rather would “mobilize” that sum through grants, recategorization of Official Development Assistance (ODA), loans, carbon markets, and private investment.

Developed countries failed to keep their promise. Even with all the language tricks in the climate agreements, it wasn’t until 2022 that they announced they had “provided and mobilized” more than $100 billion for developing countries, forgetting that these funds were meant to be “new and additional.” [7]

The Green Climate Fund, which was launched in Cancún in 2010 and intended to be the main climate finance mechanism for developing countries, raised less than $17 billion in 15 years.

The Paris Agreement in 2015 did not increase developed countries’ pledge to “mobilize” $100 billion annually and determined that a New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) for climate finance should be established by 2025.

Late last year at COP 29 in Baku, parties to the Paris Agreement approved a decision on the NCQG that set a goal of “mobilizing” $300 billion annually by 2035 from “a wide variety of sources, public and private, bilateral and multilateral, including alternative sources.” [8] The decision also encourages developing countries to contribute to this financing through South-South cooperation.

Likewise, COP 29 established a “Baku to Belem Roadmap” to increase annual climate finance to $1.3 trillion (in English) by 2035 for “low-emission greenhouse gas developing countries.” This “Roadmap to 1.3 trillion from Baku to Belem” will seek to advance with the participation of “all stakeholders” and will be developed under the presidencies of Azerbaijan and Brazil for COP 30.

Brazil will present the TFFF as a contribution to the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG), which seeks to “mobilize” resources from public and private investors.

Alternatives from People and Nature

We must recognize tropical forests as rights holders, and not as mere providers of ecosystem services for commodification through banking instruments. To save tropical forests, it is essential to recognize that the problem is not a market failure, but rather lack of respect and protection for living systems that have the right to live and to preserve their life cycles and capacity for regeneration, to not be destroyed or polluted, to maintain their integrity and diversity, and to demand timely reparation and restoration from those who have contributed and continue to contribute to their destruction. Trees cannot be shareholders, as columnists promoting the TFFF absurdly claim. Forests are complex and dynamic communities where trees, plants, animals, microorganisms, and human communities interact, and Indigenous Peoples have ancestral practices of coexistence with forests. These living systems should not be treated as objects and commodities, but rather must have the right to sue and demand compensation from the corporations and governments responsible for their destruction.

To guard these systems, it is necessary to strengthen the real solutions already being developed by Indigenous groups, peasant communities, Black communities, quilombolas, traditional communities, and grassroots organizations. These are the actors who must be at the center of governance and be the main beneficiaries of any financing mechanism that truly aims to contribute to saving tropical forests.

We cannot reward national governments for hectares of standing forest without demanding that they adopt decisive measures to limit and reverse the irrational expansion of monoculture plantations (soy, oil palm, sugarcane, etc.), curb unsustainable livestock farming, mining, fossil fuel extraction, mega-infrastructure, mass tourism, carbon markets, and animal trafficking. It is a gross delusion to believe that allocating a payment per hectare will solve these structural problems of capitalism, which are primarily driven by private capital and companies, as well as by States.

Any initiative to protect tropical forests must promote national regulations prohibiting exports of products that contribute to deforestation, and instead provide incentives for agroecological production that contributes to forest well-being and restoration. An international regulatory framework is needed to sanction companies and countries that purchase products that destroy tropical forests. Any financing mechanism must clearly establish sanctions for States that persecute or tolerate attacks and murders of nature defenders and Indigenous Peoples.

Any financing mechanism for tropical forests must directly and transparently allocate the majority of resources to Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities, protected areas, and local governments that effectively preserve forest ecosystems.

Alternatives exist. We could raise six times more annual resources than the TFFF would ($26.4 billion) by allocating just 1% of all national defense budgets to a fund for forests. It is unacceptable to use public funds for military spending while the survival of forests depends on stock markets. Applying a tax of just $1 per barrel of oil could raise almost ten times more per year ($38 billion) than the $4 billion the TFFF hopes to raise annually through unsecured investments amid the crisis of change and biodiversity loss and the chronic crisis of capitalism.

The survival of tropical forests will never be guaranteed through false solutions that seek to generate revenue for national governments and profits for private investors rather than addressing the crisis facing these vital ecosystems. Debates about the “Roadmap from Baku to Belem” are a distraction, as our real challenge is to prevent wildfires from ravaging tropical forests again this year. The fate of tropical forests does not depend on government negotiations at COP 30—which, like previous climate summits, is co-opted by corporate interests. It depends on what we as members of civil society, Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities do to foster and multiply territories free from wildfires, deforestation, and violence against living systems.

TFFF In a Nutshell

- It seeks to place a monetary value on the ecosystem services of tropical forests.

- It would pay $4 per hectare of standing forest annually based on the targeted profitability of $125 billion in loans.

- Payments per hectare would be made to national governments, allowing them to freely decide what to do with the money.

- 20% of the $4 per hectare would be allocated to Indigenous Peoples and local communities.

- The payment per hectare would decrease if investment profitability declines.

- Loans/investments would begin to be repaid after the tenth year of operations.

- The fund could be liquidated if “exceptional” financial or other situations arise.

- Countries would have to have their own or a third-party system to monitor their forest cover by satellite.

- The TFFF would complement other market-based approaches to forests, such as REDD+.

- The mechanism would not generate carbon credits, but would allow investors who purchase TFFF credits to be greenwashed.

- The World Bank would be the main candidate to administer the TFFF.

[1] Center for Global Development, Proposed Governance Arrangements for TFFF. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/resrep29744.4.pdfhttps://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/tropical-forest-finance-facility.pdf

[2] Brazilian Ministry of Finance and Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change, Tropical Forest Finance Facility (TFFF), Concept Note, 5 July 2024.

[3] Brazilian Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change, Ministry of Finance, and Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Tropical Forest Forever Facility (TFFF), Concept Note, 24 February 2025.

[4] The concept of environmental services or ecosystem services is controversial because it views nature not as a whole system of which we are a part, but rather as a provider of services that can be identified, fragmented, isolated, assigned a monetary value and commercialized.

[5] Presidency of the Republic of Brazil, “En la COP16, cinco países confirman su apoyo al Fondo para los Bosques Tropicales,” 31 October 2024. https://www.gov.br/secom/es/ultimas-noticias/2024/10/en-la-cop16-cinco-paises-confirman-su-apoyo-al-fondo-para-los-bosques-tropicales

[6] Katie Reytar, Peter Veit and Johanna von Braun, World Resources Institute, “Protecting Biodiversity Hinges on Securing Indigenous and Community Land Rights,” 22 November 2024. https://www.wri.org/insights/indigenous-and-local-community-land-rights-protect-biodiversity

[7] OECD, Climate Finance Provided and Mobilised by Developed Countries in 2013-2022.

[8] https://unfccc.int/documents/644460

[9] Manuela Andreoni, “An ‘Elegant’ Idea Could Pay Billions to Protect Trees,” New York Times, 3 October 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/10/03/climate/brazil-climate-fund-trees.html