Welcome to Forest Cover No. 54. Forest Cover is Global Forest Coalition’s newsletter. It provides a space for environmental justice activists from across the world to present their views on international forest-related policies.

This 54th edition of Forest Cover called “Latin America’s veins remain open,” a title inspired by Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano’s landmark book, has a special emphasis on Latin America. It exposes the pillaging of Latin America by the neoliberal trade and development model. It will specifically look at the impacts of commodity production and corporate free trade on forests, indigenous territories, and local communities in this region. As Argentina gears up for the World Trade Organization’s ministerial in December, and the EU Mercosur trade talks are projected to conclude at the same time, the dangers from this trade model to forests and communities become even more apparent and necessary to expose. Unsustainable livestock production, deforestation, monoculture tree plantations, excessive use of pesticides, expanding swathes of genetically modified soya for animal feed, displaced communities are just some of the destructive impacts that such trade deals will aggravate. This edition will showcase stories from Chile, Paraguay, Argentina, and Brazil. It will also analyse the two key trade deals WTO and EU –Mercosur and reveal the consequences on forests and communities.

You can download the print version or read the articles individually below. To subscribe to the newsletter, please write to gfc@globalforestcoalition.org.

Download the print version (web quality) or (low resolution PDF)

Contents:

Exploitation in the name of trade: Latin America and the rest of the Global South

Forest-destroying beef and ethanol: the secret ingredients being used to cook up a WTO deal in Buenos Aires?

How the neoliberal model ‘locks in’ industrial livestock and harms communities

A Victory Against Encroachment by Industrial Forestry

The Struggle of the ‘People of the Earth’ (Mapuche)

Agribusiness in Paraguay: “They are Putting Our Survival at Risk”

The expansion of Brazil’s ‘soy-meat complex’ threatens the Cerrado

Exploitation in the name of trade: Latin America and the rest of the Global South

By Diego Cardona, Global Forest Coalition, Colombia

Around the world, the production of raw materials, widely known as ‘commodities’ (even in Spanish), is causing severe impacts on natural wealth, territories, and the peoples that inhabit them. Latin America is no stranger to this reality, and until a solution is sought, it would seem that the impacts are becoming greater each day.

What lies behind the conflicts caused by the production or extraction and sale of these products is a logic of domination that extends from the symbolic to the semantic and from the political to the economic plane. A readily available example is the drafting in Spanish of this editorial analysing the impacts of ‘commodities,’ a term for which an equivalent must be sought, for although corresponding words exist in various languages, the English term is imposed. In the same way, peoples and territories are suffering the imposition of an economic model that constantly speaks of increasing yields and production without allowing the space to question for whose benefit and at whose expense, and even less where it should occur.

History has largely ignored the relationships between cultural adaptations to natural environments and the forms of social organization required to maintain them. This omission has been reproduced by representations of nature in which it is portrayed as simply material or energy for the production and reproduction of capital, and its functions are valued in terms of the ‘services’ they can provide to human beings. This implies a depoliticised conception of the environment, allowing profoundly political decisions that affect all forms of life to be made by technocrats.

Cutting sugar cane in Colombia. GFC

This edition of Forest Cover offers an analysis, from various perspectives, of the impacts of the production and sale of raw materials or ‘commodities’ for international trade and the rules and institutions that facilitate that trade. In Latin America in particular, the economies are going through another process of raw-materialisation—that is, under the framework of the rules of neoliberalism and free trade, they have been assigned the role of providing raw materials, largely from extractive industries, without transformation or value-added processing.

In the current political context of the region, it is even more relevant to question the ends of this type of economic model and work to transform it, prioritising local territories, peoples and communities. Although the economies of several countries in the region are growing or recovering, it is important to be careful in interpreting what this means, for it is not necessarily beneficial for the whole population—in many cases it brings increasing inequality and a poor distribution and accumulation of monetary wealth in the hands of a few.

Latin America and other countries in the Global South produce an enormous quantity of commodities associated with the exploitation of their natural wealth: oil, carbon, gold, coffee, soya, beef, palm oil, paper pulp and cellulose, among others. The majority of the industries that generate these products are among the main underlying causes of deforestation, and by extension, are responsible for the violations of the individual and collective rights of the local peoples and communities living in exploited territories.

The destruction, degradation or disappearance of any type of ecosystem should be evaluated in terms of all of its aspects, given that there are no strategic ecosystems that are of greater or lesser importance than others; they all have a series of indispensable functions and contain natural wealth that is of equal importance for survival. Meanwhile, all biomes or ecosystems are part of territories that are home to peoples or communities whose rights must prevail, and this requires a reconsideration of the purpose, quantity and forms of material production and consumption that cause the impacts referred to here.

Monoculture tree plantations for the exploitation of wood, for example, requires immense swathes of land where nutrients are extracted from the soil, and water sources in the surrounding ecosystems are affected, as demonstrated by examples in Chile, Brazil and Uruguay, as well as in other countries in Africa and Asia. Palm oil monoculture is expanding at a rapid rate in Mexico, Honduras, Ecuador, Colombia and Peru at the expense of forests and other ecosystems which are disappearing. In many cases, this process is accompanied by complaints about the displacement of local communities or human rights violations; the sad case of Indonesia is an example.

Widespread cattle ranching, in addition to being responsible for deforestation and ecosystem degradation, causes and even increases inequality in landholdings, a problem that has reached critical levels in countries such as Paraguay, where 2.6% of landowners possess 85.5% of the territory. That country is now the world’s fourth largest exporter of soya, much of which goes to feed cattle in the European Union, United States and Russia. The effects of this agroindustry are also visible in Argentina, Bolivia and Brazil, where unique biomes such as the Chaco and the Pampa are shrinking drastically, with thousands of hectares having disappeared completely.

Violence in Bagua, Peru. Powless/Flickr

With regard to mining, multiple examples bring to mind the disastrous effects of this industry. Its impacts have many manifestations, including the violent methods used to enter and usurp territories, as occurred in Bagua in the Peruvian Amazon in 2009, where the State’s use of force to repress a demonstration by Indigenous Peoples that would be affected by a mine resulted in the death of 33 people. In other cases, existing minerals exploitation has caused the destruction of ecosystems, contamination, and the loss of the means of production and conditions for the endurance of communities in their territories.

With things as they are, it is logical that social mobilisation and resistance will grow in every corner of Abya Yala (the ‘continent of life’ in the language of the Kuna people). Unfortunately, this is costing the lives of hundreds of men and women defenders of human and environmental rights, with critical situations in Honduras, Colombia and Brazil, and conditions in other countries in the region that continue to be alarming. Added to this is the growing criminalisation of protest and mobilisation throughout the region.

The results of the next rounds of negotiations of the World Trade Organization (WTO)—to be held in Argentina—and the EU-Mercosur trade negotiations could worsen the situation, especially because of the Mercosur countries’ probable focus on using both sets of negotiations to further increase exports of beef to Europe. The harmful effects of increasing industrial production of commodities such as beef and soy on forests and peoples will be swift.

This situation is worsened by the fact that the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) uses a simplistic definition of forests that wrongly includes plantations, which has led to, among other consequences, the logging of native forests and the occupation of immense areas by monoculture tree plantations to produce pulp to make paper, cardboard and packaging that is quickly discarded. Millions of these hectares that are covered temporarily by monocultures and periodically logged, leaving naked soil, were previously home to Indigenous Peoples and local communities that have been displaced, stripped of their livelihoods and forms of social reproduction, and forced to take temporary and poorly paid work.

At the recent 44th session of the UN Committee for Food Security (CFS), which addressed the issues of sustainable forestry for food security and nutrition, representatives of social movements and civil society influenced the drafting of an official document providing recommendations for states. They included the need to create space within the CFS to discuss the impacts of industrial tree plantations on food security and nutrition, which are undermined by landgrabbing, the destruction of traditional productive practices and/or the privatisation of access to sources of water and land for hunting or gathering for millions of people. The document also recognises the spiritual, cultural, social, political and economic dimensions and relationships that exist between forests and the peoples that depend on them, as well as the contribution of these peoples to feeding humanity. No less important is the need to continue advancing in the recognition of women’s rights and the control of territories by their legitimate inhabitants.

The opening of this door means recognising impacts that have historically been ignored; and keeping it open and going through it is part of the task we face, one that continues to bring us together and give us hope, as we face the next WTO gathering in Buenos Aires and the Mercosur negotiations with the EU, which threaten the world’s forests and peoples.

Forest-destroying beef and ethanol: the secret ingredients being used to cook up a WTO deal in Buenos Aires?

By Ronnie Hall, Global Forest Coalition, England

If anyone tells you that beef, biofuels and forests have nothing to do with the eleventh ministerial conference (MC11) of the World Trade Organization (WTO), which is taking place in Argentina in December, don’t believe them. Although it may not be apparent when reading the WTO’s planned agenda, it is quite possible that the WTO outcome could be implicated in another commercial assault on Latin American forests—in spite of governments’ global commitment to halt deforestation by 2020 (under Sustainable Development Goal 15, Sustain Life on Land).

Why? Because two sets of trade negotiations, the WTO and the EU-Mercosur negotiations (between the European Union and Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay), will be taking place at almost the same time and in pretty much the same countries—and it looks as if they are being tied together, by the EU and Brazil in particular, so that each can maximize its returns in both sets of talks.

At the time of writing, the EU-Mercosur talks seem to be hurtling towards a conclusion. After years of delay and stagnation, today’s negotiators see a window of opportunity that may soon close, because of the uncertainty engendered by general elections due in Brazil and Paraguay in 2018 and Uruguay in 2019. They talk of completing negotiations by the end of 2017. But how can they seal a deal in just a few weeks, when the two sides have failed to reach agreement for over two decades?

A key sticking point in the past has been the fact that the Mercosur countries, headed up by Brazil, have refused to continue unless the EU offers preferential market access for its beef and ethanol exports. [1] Additional reasons have been Latin American countries’ failure to open up certain markets to EU exports; and the EU’s refusal to cut domestic support to its farmers. [2]

Cattle in Brazil. Eduardo Amorim/Flickr

How beef and ethanol production impact on forests

Cattle-ranching is already responsible for some 60% of Brazil’s deforestation. Current and degraded and abandoned grazing lands now exceed almost a quarter of Brazil’s territory. [3] Recent expansion cycles are the main cause of destruction in the Amazon, and even more so in the Cerrado. The conversion of Paraguay’s territories to cattle and soy production is similarly dramatic. Although it is a relatively small country, it joins Brazil, Chile and Nicaragua as a group of four countries that account for over 97% of the conversion of forest to pasture in Latin America. [4]

Ethanol, which can be used as a transport fuel, can be produced from sugarcane. However quantifying the degree of deforestation that is due to sugarcane is difficult, for a number of reasons, including a lack of available data. However many researchers argue that sugar production has indirect impacts on forests such as the Amazon, by replacing other crops that are then grown in areas cleared of forest (often as a result of illegal logging). [5]***

European farmers, especially Irish and French cattle farmers whose livelihoods are threatened, had previously managed to get beef and ethanol exempted from the talks. But early in 2017 the European Commission (EC) suddenly backtracked, choosing to ignore its farmers, as well as the risks of extensive deforestation in Latin America, and the health scandals that have recently engulfed the Brazilian beef and poultry sectors. [6] It offered Mercosur preferential access for certain quantities (quotas) of beef and ethanol (along with similar offers on poultry, pork and maize). [7] Suddenly, the EU-Mercosur trade negotiators were talking numbers, not sectors, and measuring the talks in weeks rather than years.

But why should the EC suddenly change its position like this? Perhaps the answer actually lies in what the Mercosur countries might be able to deliver for the EU somewhere else—perhaps in the WTO.

For example, even though the formal agenda proposed for the WTO has an overt and ‘new’ focus on e-commerce (through which industrialised countries are aiming to promote the interests of digital giants like Google and Amazon), the real meat of the debate is still an intense North-South conflict about whether industrialised countries will reduce domestic support for their farmers, and go along with developing countries’ need to maintain public stockholdings (PSH) of food to promote food security.

At the very epicentre of the dispute we find a joint proposal on both of these issues—domestic support and PSH—coming from none other than the EU and Brazil, working in tandem. [8] If the EU is seen to be partnering with Brazil on such a sensitive issue, whether or not it is successful, it could potentially pave the way for EU ‘wins’ in other key areas, such as e-commerce and related new issues such as investment (both of which are also highly problematic in social and environmental terms). [9] It may also enable the EC to convince some recalcitrant EU member states to look more favourably on an EU-Mercosur deal. [10]

Harvesting sugar cane. Sweeter Alternative/Flickr

Is this Brazil doing a deal with the EU in return for getting what it wants on beef and biofuels in the EU-Mercosur talks? It must be expecting something in return. One’s suspicion about this grows when one finds that the EU-Brazil proposal doesn’t even address the exempted ‘green box’ subsidies that account for about 90% of the EU’s agricultural subsidies. [11, 12] Brazil has even declared that it would like to announce the EU-Mercosur deal at the WTO’s MC11. [13]

Secondly the Mercosur countries have made a proposal on ‘Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises’ (MSMEs) [14] promoting a work programme that includes e-commerce. [15] Critically, the progressive sounding MSME approach has been described as a Trojan horse for delivering new issues such as Investment Facilitation, part of the EU’s hugely divisive ‘New Issues’ agenda, [16] which has already been roundly rejected by developing countries and led to the collapse of the WTO Ministerial (MC5) in Cancun in 2003. [17] If the current proposals on e-commerce were agreed, they could prevent developing countries developing their own digital industries, allowing a free flow of e-commerce opportunities for the digital giants instead. [18]

Thirdly, Argentina is the Chair of the Buenos Aires talks. This role inevitably confers a considerable degree of influence on Argentina, including in terms of process—a power that is often blatantly abused by WTO Chairs seeking particular substantive outcomes. [19] Argentina has it within its gift to slant the negotiations in the EU’s favour in the final fevered hours of negotiation. And Argentina is after those beef export quotas too.

Argentina joins Brazil in wanting to announce that the EU-Mercosur deal has been sealed during MC11. [20] One can only wonder if this is another sign that the EU and Mercosur countries have converging interests in the WTO. Or is this a final turn of the screw in the Mercosur countries’ efforts to wring every last drop of advantage out of the EU-Mercosur talks whilst in Buenos Aires?

Let’s hope not. For the sake of Latin America’s forests and forest-dependent peoples and communities, the EU-Mercosur and WTO deals have to be stopped. We should reject the current corporate free trade model that ‘locks in livestock’. There are many feasible alternatives capable of producing more and better quality food without destroying the world’s forests.

[1] Euractive.com, 11.9.2017, https://www.euractiv.com/section/economy-jobs/news/brazil-tells-the-eu-it-wont-move-without-ethanol-and-beef/

[2] Bilaterals.org, http://bilaterals.org/?-EU-Mercosur-

[3] Mongabay, 20.11.2016, http://data.mongabay.com/brazil.html

[4] FAO, 2013, www.fao.org/docrep/018/i3437e/i3437e.pdf

[5] CIFOR, 2011, https://www.cifor.org/publications/pdf_files/

WPapers/WP68Pacheco.pdf

[6] BBC, 20.3.2017, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-latin-america-39334648 and Reuters, 23.3.2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-brazil-corruption-meat-eu/eu-asks-brazil-to-suspend-meat-shipments-amid-scandal-sources-idUSKBN16U2Z5

[7] Media reports mention offers on beef, ethanol, poultry, pork and maize. European Parliament, 3.10.2017, http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?type=WQ&reference=P-2017-006181&format=XML&language=EN However the only formal mention is of offers on beef and ethanol: European Commission, October 2017, http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2017/october/tradoc_156336.pdf

[8] The paper is also co-sponsored by Uruguay, Peru and Colombia. European Commission, 17.7.2017, http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-17-2031_en.htm

[9] For more about the EU’s ‘new issues’ agenda see: Woolcock S, London School of Economics, undated, http://www.lse.ac.uk/internationalRelations/centresandunits/ITPU/docs/woolcocksingaporeissues.pdf

[10] Farming Independent, 17.10.2017, https://www.pressreader.com/ireland/irish-independent-farming/20171017/281505046449387

[11] “The EU-Brazil proposal on domestic support as a percentage of OTDS is flawed because the OTDS does not include the allegedly decoupled subsidies notified in the green box which today account for about 90% of the EU agricultural subsidies.” E-mail from Jacques Berthelot to wto-intl listserv, 6.11.2017. (OTDS stands for Overall Trade Distorting Subsidies, and ‘green box’ refers to subsidies that are exempted from WTO disciplines because they are considered to be non-trade or minimally trade distorting.).

[12] European Parliament, June 2017, http://www.europarl.europa.eu/atyourservice/en/displayFtu.html?ftuId=FTU_5.2.7.html

[13] IATB, 2017, http://conexionintal.iadb.org/2017/09/01/brasil-aspira-a-anunciar-acuerdo-mercosur-ue-a-finales-de-2017/?lang=en

[14] WTO, 9.6.2017, JOB/GC/127

[15] South Centre, 3.10.2017, https://www.southcentre.int/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/IN_High-Stakes-in-MC11-30-Oct-2017_EN-1.pdf

[16] South Centre, 30.10.2017, https://www.southcentre.int/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/IN_High-Stakes-in-MC11-30-Oct-2017_EN-1.pdf (p8)

[17] Woolcock S, London School of Economics, undated, http://www.lse.ac.uk/internationalRelations/centresandunits/ITPU/docs/woolcocksingaporeissues.pdf

[18] South Centre, 30.10.2017, https://www.southcentre.int/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/IN_High-Stakes-in-MC11-30-Oct-2017_EN-1.pdf (p6)

[19] Third World Network, 21.12.2005, http://www.twn.my/title2/twninfo336.htm

[20] Farming Independent, 17.10.2017, https://www.pressreader.com/ireland/irish-independent-farming/20171017/281505046449387

How the neoliberal model ‘locks in’ industrial livestock and harms communities

By Ronnie Hall, Global Forest Coalition, England, and Mary Louise Malig, Global Forest Coalition, Philippines

Family farmers and rural communities around the world, including in Latin America, are struggling to maintain their sustainable farming practices, livelihoods and traditional cultures in the face of the rapid industrialisation and corporate concentration of agriculture, especially in the livestock and related feedstock sectors.

This expansion and industrialisation of agriculture comes at a high price to communities’ and animals’ health and wellbeing as well. The farming of cattle in ‘Concentrated Animal Feedlot Operations’ (CAFOs) such as mega-dairies means that millions of animals are being raised in inhumane, unsanitary and polluting industrial conditions. The unnecessary use of antibiotics is leading to drug-resistant bacteria and the spread of untreatable bacterial infections. Final food products can contain a cocktail of pesticides, hormones, parasites and/or bacteria. In addition, the industrial production of feedstocks, such as pesticide-sprayed soya in Paraguay, is polluting communities’ water sources.

Battery cage hens at a facility in India. Brighter Green/CIC

There are also significant impacts on forests (see box on page 6) and climate change. Livestock is responsible for 14.5% of global greenhouse gases, with beef and cattle milk production being the worst culprits. [1] These problems can be expected to intensify unless they are addressed now, as demand for meat is anticipated to grow by 70% by 2050.

India’s poultry sector exemplifies the problem of corporate concentration. A relatively recently introduced ‘vertical integration model’ means that the large exporting companies control all aspects of production, owning the chickens from before they hatch to the day they are slaughtered taking on contracted farmers to do most of the work. Critically this has almost replaced communities’ backyard poultry production, which was mostly undertaken by women for their own families’ consumption and for additional income.

The Brazilian beef sector is another prime example. Brazil introduced a so-called ‘national champions’ policy that favours large companies who are expected to advance the country’s interests internationally as they prosper. This has put many small slaughterhouses out of business, and made life much harder for small cattle breeders, who became captive to the big slaughterhouses, which pay them lower prices and grab their profits.

Cattle market in Argentina. Christopher Gollmar/Flickr

Boosting livestock exports by opening up new export markets is often a key goal in free trade negotiations, regardless of these impacts. Besides the EU-Mercosur negotiations, examples include the EU-Canadian Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA), which is very much focused on trade in milk, cheese and beef; [2] the EU-Japan free trade deal that has been dubbed ‘cars for cheese’ with meat and cheese exports to Japan being a major European priority; [3] and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) between the US and the EU, whose fate rests to a great extent on whether trade negotiators can force reluctant European consumers to swallow American chlorine-washed chicken imports. [4]

The World Trade Organization (WTO), with its powerful Dispute Settlement Mechanism, also locks-in livestock in ways that benefit the biggest industrial agriculture corporations through its Agreement on Agriculture (AoA). When the AoA was being negotiated, a list of promises was made to developing countries to induce them to agree to include this sensitive sector in the WTO. These promises included the removal of trade-distorting export subsidies for agriculture in developed countries such as the US and the EU member states, and promises of additional market access in agricultural sectors in the North for developing countries. But in practice the AoA has actually allowed the US and the EU to increase their subsidies. A stark example of the consequences of this is the decline of the domestic poultry sector in Ghana and other West African countries in the face of subsidised production and export from the EU. This row over subsidised agricultural production will be central to the negotiations at MC11 in Buenos Aires.

The WTO is also relevant to livestock through its involvement in standard setting. Its rules work against the permanent use of the precautionary principle, an approach often used to take action on key environmental issues even if scientific evidence is lacking. In the run up to MC11 the International Beef Association is calling for the “alleviation of unscientific and unjustified impediments” which impose “unwarranted costs on value chains”, as well as reductions in domestic subsidies. [5]

Treaties designed to promote cross-border investment also take a heavy toll on rural communities and their agriculture with land grabbing being rife. For example, in Bolivia, incoming Brazilian livestock investors have taken advantage of the low cost of land and free trade ‘tariff preferences’ under the Andean Community (CAN) agreement. Uruguay has seen cattle ranches bought up by foreign investors, and an influx of foreign meat packing companies, especially Brazil’s Marfrig. [6] In Paraguay, the problem of land being grabbed from small farmers and Indigenous Peoples for cattle-ranching and soy production remains a key preoccupation, including because it is systematically undermining the country’s capacity to produce food for local consumption. Argentina has seen its world-famous beef sector transformed from extensive grass-fed production to CAFOs, with land being given over to soy production instead, to feed Europe’s cattle. [7]

This summary is sourced from Global Forest Coalitions three publications on the livestock sector, written variously by Mary Lou Malig and Ronnie Hall:

– What’s at Steak?: the real cost of meat

– WTO and Livestock: starving small farmers, feeding large agribusinesses

– Our food is not your business: alternatives to unsustainable livestock and feedstock farming and the current corporate free trade model.

[1] Food and Agriculture Organization, 2013, http://www.fao.org/docrep/018/i3437e/i3437e.pdf

[2] Financial Post, 20.11.17, http://business.financialpost.com/news/economy/canada-eu-launch-free-trade-agreement-while-britain-eyes-its-own-deal

[3] Financial Times, 6.7.17, https://www.ft.com/content/572fef42-6260-11e7-91a7-502f7ee26895

[4] Friends of the Earth Europe, 2015, http://www.foeeurope.org/rotten-deal-110315

[5] International Beef Alliance, 20.10.17, http://internationalbeefalliance.com/pdf/2017/releases/IBA_Statement_-_Final_version_ESP.pdf

[6] GRAIN, 13.10.10, https://www.grain.org/es/article/entries/4044-big-meat-is-growing-in-the-south

[7] Development & Cooperation Journal, 10.10.15, https://www.dandc.eu/en/article/cattle-industry-argentina-changing-rapidly-not-better

A Victory Against Encroachment by Industrial Forestry

By Darío Aranda, journalist with Friends of the Earth Argentina

El Dorado is located some 200 kilometers from the provincial capital of Misiones, which is located in the extreme northern region of Argentina, and known for its beautiful landscapes and biodiversity.

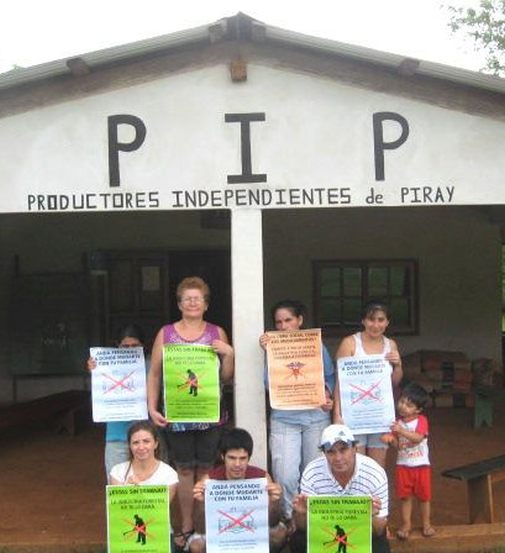

Productores Independientes de Piray (PIP)

Yet close to the centre of the city, no more than ten minutes by car, everything becomes monotonous. The serried ranks of trees that appear resemble an army: green, meticulous, in line. Pine monocultures stretch out in long rows for hundreds of metres, disappearing into the horizon. Along neighbouring dirt roads are the humble homes of rural families that have resisted corporate encroachment for a decade.

This is ground zero for the multinational Alto Paraná (Arauco), which controls 10% of the territory of the province (256,000 hectares) and has been expanding its forest monocultures. It is the largest private landholder in Misiones, and in municipalities such as Piray, it controls 62% of the land.

This has involved the eviction of small farmers and Indigenous People, and the deforestation of native forests. Remaining rural families have found themselves surrounded by pine trees, leaving them only 1400m2 (less than a fifth of a hectare per family). It is impossible to live off the produce from such small parcels of land.

A group of two dozen rural families organised to defend themselves, forming the Cooperative of Independent Producers of Piray (PIP, using its initials in Spanish), which has said ‘enough!’.

They share a common anguish and a determination not to leave their land, to maintain their farming lifestyle and refuse to give in to corporations or politicians.

Wilderness and communities have disappeared in the zone where forest cultivation has expanded. One consequence of this has been a rural exodus. In its collective resistance to the evictions, PIP was an exception. The collective went even further, demanding that the State expropriate land from Alto Paraná. In June 2013, they succeeded in getting Law XXIV-11 passed, to expropriate 600 hectares. That law recognises the negative impact of forest agribusiness, stating: “In the years 1997 and 1998, favoured by liberal policies detrimental to the people of Misiones, the process of the concentration of land was begun by the company Alto Paraná, and countless jobs were lost, leading to rural exodus.” It points out the mass disappearance of small farms.

Farmers celebrated the expropriation of the land in 2013, but they soon noted a lack of compliance. Their banners read: “Sowing our struggle, we harvest 600 hectares.”

The government of Misiones has taken four years to hand over the first 166 hectares, and only did so because PIP continued to mobilise and demand compliance with the law. Since mid-2017, farmers have worked the land destroyed by the multinational. They began by cleaning up the waste left behind from the pines (even without the machinery promised by the government), and then they began planting.

Communities in Argentina protest against pine monocultures. Productores Independientes de Piray (PIP)

“We’re going all out, with struggle, effort and organisation. During our first planting, we dealt with many bugs, but now we’re working with natural fungicides. And we are harvesting beans, cucumber, squash. We’re happy,” said Miriam Samudio of PIP.

A communiqué by the organisation states: “We have managed to ‘extend the horizon.’ The pines and eucalyptus are no longer in our front yard. They have been pushed back, and now the wind that blows is a little purer. It is an important achievement for the whole community. We will not go back to seeing fumigations behind our homes.”

Piray is not the only conflict facing Alto Paraná and other forestry companies. Similar resistance is occurring in the towns of Puerto Libertad, Ruta 20, the Guaraní community of Ysyry (Colonia Delicia), Paraje Nueva Argentina, and others.

The legal framework for forestry development in Argentina was initiated in the 1990s under the neoliberal government of Carlos Menem. In coordination with the companies under the umbrella of the Argentine Forestry Association (AFOA, for its initials in Spanish), Menem approved legislation that was beneficial for private business (Law 25,080), with subsidies at every step of production, from planting and maintenance to irrigation and harvesting. They are not required to pay real estate taxes on land and are exempt from payments based on gross revenues. They benefit from a VAT (Value-Added Tax) refund and can amortise taxes on profits. Article 17 of the law does not use the word subsidy, preferring the euphemism “non-refundable financial support” to explain that the State actually covers between 20-80% of the companies’ planting costs.

Menem was not alone in favouring private business, for the law expired in 2009 and was extended for another ten years (through the National Congress) by the government of Cristina Fernández de Kirchner. It now ends 1 January 2018. Claudia Peirano of AFOA has requested that the law be extended again and that modifications be considered later. The subsecretary of Industrial Forest Development (in the Ministry of Agroindustry), Lucrecia Santinoni, said that the government has “a duty to extend the law.” Six presidents came and went (Carlos Menem, Fernando de la Rúa, Eduardo Duhalde, Néstor Kirchner, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner and Mauricio Macri), and it seems that the law promoting forest monoculture will still be upheld. It is a State policy.

In fact with Mauricio Macri’s arrival as president, corporate subsidies expanded from 100 million pesos to 265 million pesos, and the Ministry of Agroindustry is promising to increase that figure to 350 million.

The amount of land dedicated to monoculture speaks volumes. From 600,000 hectares in 1998, it grew to 1.3 million hectares by 2015. The current government wants to increase that figure further, up to two million hectares, and proposes to make progress in the “cellulose industry” (the questionable “pulp mills” [1]). Misiones is Argentina’s logging province par excellence, with 59% of production.

The director of Arauco Argentina, Pablo Mainardi, said that Argentina should “have two or three more cellulose pulp mills, since it has the land and more than 940,000 hectares planted in the provinces of Misiones and Corrientes.” He advocated overturning national and provincial legislation by repealing the Constitution of Corrientes, the Land Law, the Entre Ríos Law that prohibits the transporting of logs and the Insalubrity Law in Misiones (which governs the production of unhygienic waste by paper mills).

Despite the delicate situation, on November 2017, Argentina and Chile signed a Free Trade Agreement (FTA), with Chile being the country of reference in forestry activity and FTAs. In general terms, the FTA states that Argentine products can be distributed in all countries with which Chile maintains similar zero-rate treaties, [2] and proposes to work on “a more modern and balanced legal framework for the development and protection of investments, greater agility and certainty for trade between both countries.” The Chilean Embassy in Argentina stated that the treaty seeks to “establish a framework of protection for investors, in which there is no discrimination among providers from both countries, and capital transfers can be made.”

In light of this, it is possible that the existing forestry companies will become stronger and that still others will enter the country, reigniting social conflicts by increasing competition for farmers’ lands.

[1] Argentina and Uruguay sustained a diplomatic conflict between 2006 and 2015 over the installation of the Botnia-UPM cellulose pulp mill in Uruguay (with Finnish capital). The population of the province of Entre Ríos (Argentina) is still demanding the withdrawal of the plant from riverbanks between the countries.

[2] Chile’s ambassador in Argentina, José Viera Gallo, explained that Argentine companies that associate with Chilean firms (and can process products in Chile) could export with zero duty to the 65 countries with which Chile has free trade agreements.

The Struggle of the ‘People of the Earth’ (Mapuche)

By Claudio Donoso Hiriart and Susana Huenul Colicoy, Colectivo Viento Sur, Chile

Entering this territory called Chile from the north, from the Cerro Camacara, and heading south, European invaders were met with the most spectacular and varied landscapes. Three thousand extraordinary kilometers, in a trip across the great central valley that goes from desert to forests, split by cross-cutting chains of hills snaking between the gigantic mountain ranges of the coast and the Andes. The Pacific Ocean with its cold current and the presence of the South Pacific High anticyclone and the Polar Front frame this canvas, which resembles an unusual island.

What richness stood before the impoverished eyes of those seeking only gold and slaves, who came imposing fire and swords to evangelise the ‘savages’ and make them ‘civilized’ and obedient! The invaders arrived with a yen for possessions and disaffection for nature. Only a few valued and described the marvels they witnessed, the rest were frenzied with greed.

A protest against the assassination of Mapuche activists. Sergio/Flickr

Thus began the destruction of the forests and other ecosystems found from Copiapó in the North, to the south of the country. What the invaders did not know but would soon discover is that, beneath the forests, for thousands of years, soils had been forming that were rich in nutrients and had an extraordinary capacity to store water. Their agricultural endeavors on these soils no doubt produced unexpected results that made them think these resources could be as lucrative as gold. The fever for wheat and gold became as one.

What is often overlooked is that much of this territory was inhabited by the Mapuche, against whom the invaders used all sorts of schemes and trickery in an attempt to subjugate them, along with violence against those who refused to submit. The Mapuche struggle was no longer a struggle against the elements, but rather a struggle to survive and preserve their thinking, their spirituality, their health system, their food—that is, their way of life.

Those who became landowners by usurping the land, and repressing, impoverishing and reducing the Mapuche, amassed fortunes through agriculture. But the agriculture of monoculture was so intensive and savage to the land that, in just a few years, they had degraded thousands of hectares of soil. By the mid-20th century, the Chilean State had installed another monoculture to supposedly attempt to recover the soils: monoculture tree plantations, specifically Pinus radiata, which is native to California.

During these long years, the Mapuche continued to defend their land and lives, but the most tireless struggle was for their dignity. During the bloody civil-military dictatorship led by Augusto Pinochet, the exotic tree monocultures were transformed into a forestry model for the country with grave impacts on the world of small farmers, and particularly the Mapuche.

Since the mid-1970s, during the dictatorship and particularly with the implementation of Decree-Law 701, forestry companies gained ground through juicy State subsidies that allowed them to acquire more and more land. But they also systematically used the strategy of ‘moving the fences’ of small landowners, simply stealing their land. They also took over Mapuche land, often through trickery.

This abuse of the Mapuche people, added to the impacts of the ransacking of their lands by those controlling the productive sector, prompted the migration of thousands of farming families to urban areas, worsening poverty in the cities and depopulating rural areas, leaving them at the mercy of the interests of the ultra-neoliberal model.

The current phase of the destruction of forests and other ecosystems can be seen in the impact caused by monoculture and clearcutting, that takes with it thousands of tons of soil and causes a severe reduction in the quality and quantity of surface water and groundwater aquifers. It also has perverse impacts on all areas of life, as evidenced in the current historical moment which is marked by resistance and efforts to recover knowledge in the arenas affected by forest monoculture such as food, agriculture and health, to name just a few.

A historical current of colonialism continues, that is now manifested in the neoliberal model in its extractivist phase. Communities and organisations in different territories are deploying invisible processes to defend the Mapuche ways of life. Said actions are related, for example, to the defence of water, which is essential for maintaining the crops with which we feed ourselves daily. Without water, there is no harvest. This also entails the defence and propagation of our traditional seeds, which open a window to a world of knowledge that refuses to disappear.

Celebrating Mapuche culture. Sin.fronteras/Flickr

Our Mapuche people also possess a health system, one denied for decades, that despite the overwhelming nature of the forestry model, is being recovered and transmitted to new generations, defending and promoting the propagation of what little native forest we still have, and recovering medicinal herbs, a source of knowledge of the lawentucheve (healers).

It seems pertinent to mention the obstacles that the expansion of forest monoculture puts in the way of productive initiatives based on local identities that allow communities to generate income while taking care of the environment. For example the collectors of non-timber forest products have seen their activities limited due to resource scarcity, despite the benefits of hazelnuts, maqui and mutilla, to name just a few. The same is true of ñocha, which does not grow in pine and eucalyptus monocultures, but is important for basketry.

In this way, we can continue opening windows to knowledge about our daily realities, even though they have been made invisible by the hegemony of the media, which insists on reproducing the discourse of ‘terrorism’ about the Mapuches in order to protect and perpetuate an industry that is destroying not only the territory in which communities live, but also a large part of the Bío Bío region, where the government has disregarded the health and quality of life of inhabitants.

Agribusiness in Paraguay: “They are Putting Our Survival at Risk”

By Inés Franceschelli, Heñoi, Paraguay

One of the smallest countries in South America, land-locked Paraguay is a raw materials producer lacking in industrial development. It is home to 6.8 million inhabitants and 14 million cattle. It is rare for important news stories to emerge from this small country, but one such moment came in June 2012, when President Fernando Lugo was ‘unseated’.

Not long afterward, the reasons for this ‘parliamentary coup’ promoted by the opposition began to surface, revealing that agribusinesses had played a key role in the political manoeuvers. Given the great inequality that exists regarding the concentration of land in private hands in Paraguay, [1] it comes as no surprise to find that efforts to control genetically modified organisms (GMOs) had been strongly contested by the new powers in government, who want to turn the country into an agro-industrial production site for export products, jeopardising the food security of the Paraguayan population.

Women walking through a genetically modified soy bean field. Luis Wagner/GFC

In 2016, this country, the world’s fourth largest producer of genetically modified soya, produced 10 million tons that were sent abroad, each ship carrying with it the richness of the soil and the water, and health of the people. [2] Paraguay is also the world’s ninth largest meat producer; in 2016, it exported 240,000 tons of beef. [3]

This enormous productive capacity has grown consistently; in 2009, 2.5 million hectares of genetically modified soya were being grown, an amount that has now reached 3.5 million hectares, an increase of 34% over eight years. [4] However, the technology imposed on the country by companies that control the agricultural business has caused an even more rapid growth in damage caused by unsustainable production; while the country imported 9.2 million kilos of agrochemicals in 2009, this rose to a whopping 44.2 million kilos in 2016, an increase of 478%! [5] Foreign and domestic companies defend their flexible norms, and, sheltered by the power of the labour unions that connect them, they have managed to engineer a situation in which all three branches of government ensure impunity for their practices. Paraguay has thus become a paradise for free trade.

“Free trade is nothing more than the protection of investments by companies, and it definitely has a negative impact on farming communities,” says Marcial Gómez, Deputy Secretary General of the National Federation of Farmers (in Spanish, Federación Nacional Campesina or FNC). He adds: “for agricultural producers, the so-called free-market means freeing up the entry of goods from large corporations into our countries, but for the small producer, there is no free market. For example, to export the production of the small producer, there are obstacles on all sides, but for large corporations that invade our country and our communities with their merchandise, there are no obstacles.”

“We cannot compete; we cannot even coexist”

Marcial Gómez, Secretario General Adjunto de la Federación Nacional Campesina (FNC)

Gómez exercises his leadership by holding frequent debates and assemblies in the farming communities that belong to the Federation. He has firsthand knowledge about the lives of residents of the settlements, as he himself is an agricultural producer under constant pressure from the monocultures. He states: “We know very well that the so-called developed countries subsidise agriculture, and they invade our markets that way. This is one of the basic problems for farmers, ‘competing’ with large corporations that have more and more advantages. We cannot compete; we cannot even coexist with this model. Our country has great natural wealth, but the corporations and large landholders do what they want here, they poison everything – the soil, the water, the air, the people. They use prohibited poisons around the world, they destroy our crops, our animals. And since they are never satisfied, for example, they increasingly try to put water and our services in the hands of the private sector that has relationships with the large multinational corporations, to use them for their economic advantage, and that is a very big setback for the people, especially for workers.”

Lowered prices for raw materials, soil degradation and the need to invest more and more in inputs to combat ‘weeds’ has led agribusiness companies to diversify. Five years ago, they imposed GMO technologies developed for corn and cotton. As there was heightened popular and institutional resistance to the spread of these technologies, they did not hesitate to stage a coup d’état to install a friendly government that would advance their products. They are currently promoting irrigated rice across large areas, and forest monocultures of eucalyptus that are intended to satisfy their demand for biomass (wood) to dry grain in their silos.

In this regard, Gómez says, “Unfortunately, Paraguay is nearly the world leader in deforestation, and the government now adds flexibility by decree to allow it to accelerate. This will further accelerate the destruction of forests, the problem of climate change, all of the adversities that are occurring in the country and the world, and the modification of the rules by the president is for his own personal benefit and that of his allies. The comrades are aware of all the problems brought by monocropping. First it was soya, now eucalyptus is another monocrop that has come to destroy the crops of small producers that have historically produced healthy foods for the Paraguayan population. For us, there is a constant debate about this. For example, in the Huber Duré settlement, the comrades conserve nearly 40% of the settlement as a forested area, they take care of the waterways because climate change is increasingly affecting small producers, they [the businesspeople] are responsible for putting our survival at risk, and that is why there is constant debate and the promotion of practices that can help maintain equilibrium.”

Paraguay’s National Federation of Farmers is counting on organisation for resistance, and resistance for survival.

[1] In Paraguay, 90% of the land is in the hands of 12,000 large landholders, while the remaining 10% is distributed among 280,000 small- and medium-sized producers. (Yvy Jara, Los dueños de la tierra en Paraguay. Informe de investigación. Guereña, Aratxa y Rojas, Luis, eds. Oxfam 2016).

[2] http://www.abc.com.py/nacionales/cosecha-de-soja-alcanzara-casi-10-millones-de-toneladas-616379.html

[3] http://www.ultimahora.com/carne-el-2016-se-exporto-n1053316.html

[4] http://capeco.org.py/area-de-siembra-produccion-y-rendimiento/

[5] To read more about the history of agrochemical imports, see “La principal actividad económica nacional no es nacional”, in: Con la soja al cuello (2016). Available here: http://www.baseis.org.py/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/informe-agronogecio-2016.pdf

The expansion of Brazil’s ‘soy-meat complex’ threatens the Cerrado

By Diana Aguiar and Letícia Tura, Federation of Organisations for Social and Educational Assistance (FASE), Brazil

Brazil’s efforts to assert itself economically on the international stage are strongly supported through the export of commodities. A central pillar of this is the expansion of industrial agriculture in the country’s second largest ecosystem, the highly biodiverse Cerrado savanna region.

Deforestation in the Cerrado. Wev’s Bronw/Flickr

Monoculture soy, primarily for animal feed, has expanded significantly in recent decades, growing 140% in 15 years. Brazil has risen to become the largest global exporter of soy, accounting for more than 42% of total global exports. [1] It isn’t surprising therefore that the ‘soy-meat complex’ is responsible for a considerable part of Brazil’s export portfolio, to the extent that soy and its derivatives represent around 18% of the total, with meat ranked a few levels below. [2]

However, the trail of devastation and conflict left by the rapid expansion of the ‘soy-meat complex’ in the Cerrado is the forgotten side of the story. On degraded lands currently used for pasture in Brazil, livestock farming already occupies 25% of land nationally and continues to expand. [3] This expansion occurs largely through landgrabbing on public land designated for traditional uses, causing intense conflicts with peasant communities, small-scale farmers, Indigenous Peoples, ‘Quilomba’ communities and other traditional peoples. Due to its continuous expansion, livestock is the main cause of deforestation in the country. It is also destroying the cultural diversity of the Cerrado and Amazon, the two ecosystems most threatened by the expansion of meat and soy.

This situation, and the need for relevant protective measures, is being ignored. Data released indicates that “deforestation in the Cerrado in this century is three times greater than in the Amazon, in proportion to the size of the remaining areas of vegetation”. [4] Yet there remains a widespread perception that vegetation in the Cerrado region is not ecologically important, and that the region is sparsely populated. Indigenous People, peasants, small-scale farmers and traditional communities in the Cerrado have historically been made invisible, as has the importance of the essential hydrological role played by the region’s vegetation. It is known as the ‘cradle of water’, and is the source of some of the main hydrological basins and aquifers in South America, such as the Guaraní aquifer and the Paraná basin.

This situation has not resulted in consistent environmental protection policies, only policies that favour agribusiness allowing them to offset environmental damage caused. The potential for attracting foreign exchange from agricultural exports and the rapid transformation of the Cerrado into a commodity production centre is very attractive to planners and investors. In addition, the historical connection that agribusiness has with the Brazilian political system gives it unique economic and political power in the country, comprising one of the most powerful and reactionary groups in the Brazilian Congress.

Satelite image of soybean farming in the Cerrado. European Space Agency/Flickr

The ‘soy-meat complex’ has thus been strongly supported by national policies which concentrate corporate power, turning national companies into transnational ones. One example is the ‘National Champions’ (Campeões Nacionais) policy of the National Economic and Social Development Bank (Banco Nacional de Desenvolvimento Econômico e Social) which, through subsidised loans, helped a group of Brazilian companies to become transnational agribusinesses, joining the giants of the global meat-packing industry. Between 2007 and 2013, when the policy was in force, the bank injected R$ 18 billion into just five companies (among them JBS and Marfrig).

The ‘National Champions’ policy was instrumental in enabling these companies to acquire the power they now enjoy: JBS is currently the largest meat producer and exporter in the world, but was not even among the 400 largest companies operating in Brazil in 2002. [5] Another more recent example is the Matopiba Agricultural Development Plan (Plano de Desenvolvimento Agropecuário do Matopiba), created in 2015. It promotes industrial-scale shrimp farming, tree plantations, and the farming of grains such as soy, which replace natural remnant vegetation, especially in the Cerrado. The plan covers 73 million hectares, accounting for 51% of the area of the states of Maranhão, Tocantins, Piauí and Bahia.

The expansion of agribusiness in the Cerrado is being exported as a model to other places, where Brazilian agribusinesses intend to invest next. This is particularly true in other areas of savanna and plains across the world, which are targeted by agribusiness for their flat land, where monocultures can expand more efficiently, using less energy.

Mozambique is an example of this. The ProSavana Mozambique-Brazil-Japan Cooperation Programme (Programa de Cooperação Moçambique-Brasil-Japão ProSavana) focuses on the north of the country, which is on the same latitude as the Brazilian Cerrado, making it possible to replicate agribusiness expansion there. Although it officially claims to be aimed at the development of rural peasant agriculture in Mozambique, the programme was designed to attract investors with access to global markets, incorporating peasant farmers in a marginal way, making them subordinate to agribusiness production chains. [6]

But the Cerrado agribusiness model isn’t only followed in Africa. In Colombia, the government refers to Altillanura, close to the Venezuelan border, as the ‘Colombian Cerrado’, where the ‘Brazilian miracle’ can be replicated. [7] In this case, there isn’t a programme of cooperation, and Brazil does not appear to play a direct role (although Embrapa technicians have already begun to provide advice on the ‘Cerrado model’ [8]). Rather the Colombian government is following its own lead. The ‘land regularisation’ issue, where communities can intervene legally to assert their rights as residents, has been raised as a hindrance by the government and agribusiness, [9] as well as by the Brazilian Minister of Agriculture and soybean mega exporter Blairo Maggi, who visited Colombia in the last eight years to evaluate the possibility of buying land. [10]

Understanding the scale of the problems involved in the ‘soy-meat complex’ should be the driving force behind a collective mobilisation between and convergence of struggles in the countryside and in the city. There are a number of collective efforts already underway in Brazil, such as the Brazilian Forum on Food Sovereignty and Security (Fórum Brasileiro de Soberania e Segurança Alimentar), the National Agroecology Organisation (Articulação Nacional de Agroecologia), and campaigns such as the Permanent Campaign against Agrochemicals and for Life (Campanha Permanente contra os Agrotóxicos e pela Vida) and the Campaign in Defense of the Cerrado (Campanha em Defesa do Cerrado). They are behind the key message of ‘real food in the countryside and in the city’. A basic assumption is that we must work towards structural changes such as Agrarian Reform, and programmes and public policies that benefit small-scale farmers.

[1] USDA, 2017.

[2] MDIC, 2017.

[3] Schlesinger, Sergio, “A cadeia produtiva de carnes no Brasil”. In: AGUIAR, Diana; TURA, Letícia (Org.). Cadeia Industrial da Carne – Compartilhando ideias e estratégias sobre o enfrentamento do complexo industrial global de alimentos Rio de Janeiro: FASE, 2016. Available here: https://fase.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Livro-Cadeia-Industrial-da-carne.pdf

[4] http://www.ihu.unisinos.br/569963-desmatamento-do-cerrado-supera-o-da-amazonia-indica-dado-oficia

[5] Schlesinger, Sergio (2016). Poucos campeões, muitos perdedores: concentração e internacionalização da indústria brasileira de carnes, FASE/GFC. Available here: https://fase.org.br/pt/acervo/documentos/industria-da-carne-poucos-campeoes-muitos-perdedores/

[6] Porto, Silvio Isoppo. Análise crítica do Plano Diretor do ProSavana. In: AGUIAR, Diana; PACHECO, Maria Emília (Org.). A Cooperação Sul-Sul dos Povos de Brasil e Moçambique: Memória da Resistência ao ProSavana e Análise Crítica de seu Plano Diretor. Rio de Janeiro: FASE, 2016. P. 18. Available here: https://fase.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/ProSavana_web.pdf

[7] SEMANA. El ‘Cerrado’ Colombiano. Julho, 2010. Available here: http://www.semana.com/economia/articulo/el-cerrado-colombiano/124179-3 Accesed on 17/08/2017

[8] EL TIEMPO. Experto habla del desarrollo del Cerrado brasileño. Janeiro, 2013. Available here: http://www.eltiempo.com/archivo/documento/CMS-12546942 Accesed on 17/08/2017

[9] LA SILLA VACIA. El futuro agroindustrial de la Orinoquía ya arrancó. Noviembre, 2010. Available here: http://lasillavacia.com/historia/el-futuro-agroindustrial-de-la-orinoquia-ya-arranco-19998

[10] EL TIEMPO. Minagricultura de Brasil quiso hacer negocios en el país. Mayo, 2016. Available here: http://www.eltiempo.com/archivo/documento/CMS-16593902 Accessed on 17/08/2017

Editorial Team: Ashlesha Khadse, Isis Alvarez and Ronnie Hall

Editors: Isis Alvarez and Ronnie Hall

Translators: Megan Morrissey and Oliver Munnion

Layout, Graphic Design & Photo Research: Oliver Munnion

Donate to GFC here.

Front cover main photo: EC DG ECHO/Flickr

Other front cover photos: Powless/Flickr, Productores Independientes de Piray y Sweeter Alternative/Flickr

This Forest Cover was made possible through support from various GFC member groups and contributors, including the The Christensen Fund, the International Climate Initiative (IKI) of the German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety (BMUB), and the Isvara Foundation.

The views expressed in this publication are not necessarily the views of our contributors.