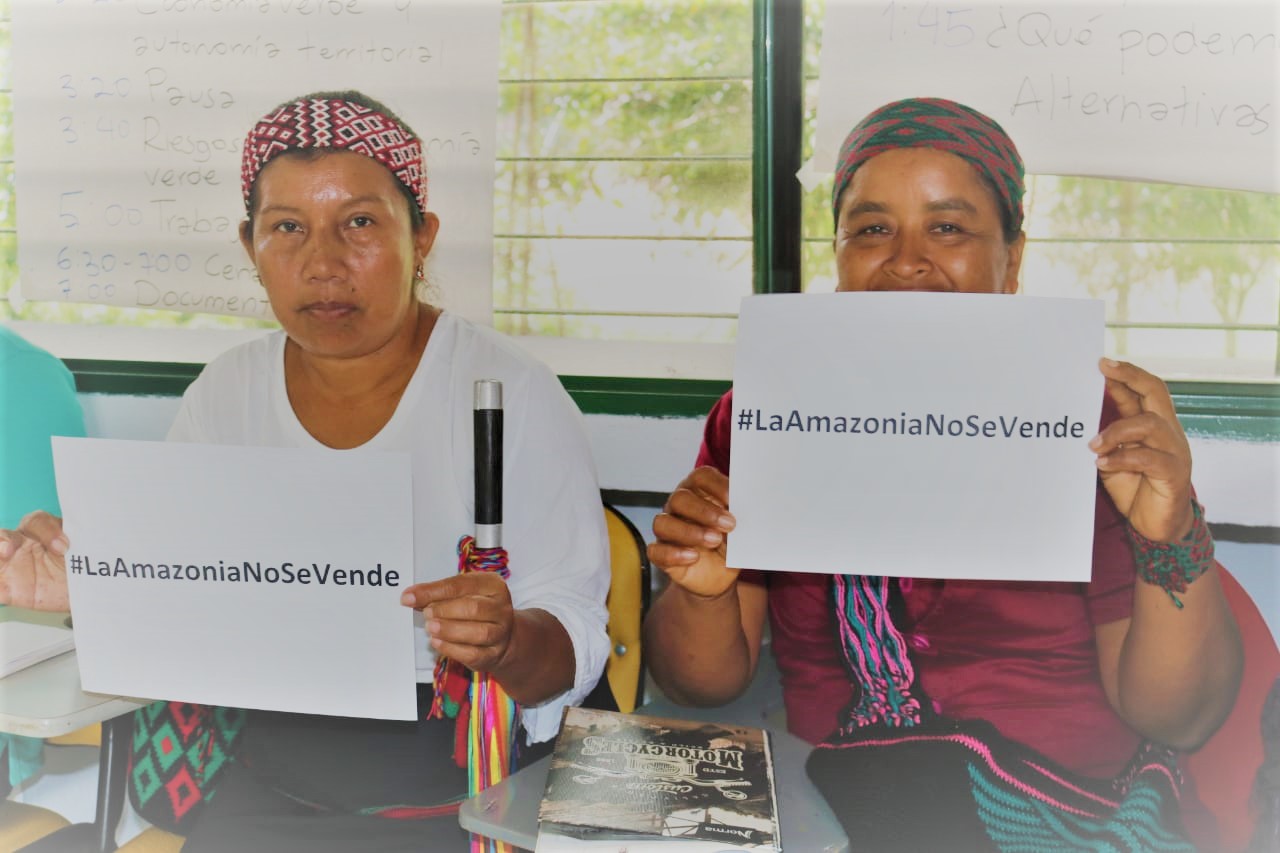

Roots of Resilience Episode 3: The Land is Not For Sale

Roots of Resilience Episode 3: The land is not for sale

In this episode of Roots of Resilience, we hear insights from our member groups in Chile, Colombia and Paraguay on the impacts of the colonial, patriarchal and extractivist model that has ransacked Indigenous peoples, traditional cultures, and natural resources in Latin America.

We also learn about the resistance and empowerment of communities on the ground, including gender-just and community-gender alternatives to this destructive model and how communities are building the path towards a sustainable balance and ‘buen vivir’ in their territories.

Tune in to listen now, and please share widely amongst your networks #RootsOfResilience

Available now in the following places and more…

-

Full transcript available below

-

Credits:

Valentina Figuera Martínez, host

Coraina de la Plaza, co-producer

Ismail Wolff, editor, co-producer

Cover Art: Ismail Wolff

Guests

- Omar Yampey, Centro de Estudios Heñói – Paraguay

- Camila Romero, Colectivo VientoSur – Chile

- Diego Cardona, CENSAT – Colombia

Audio credits:

‘Black Catbird’ by the Garifuna Collective

Licensor: Stonetree Records

Link & creative Commons license details: https://shikashika.org/birdsong/artists/the-garifuna-collective/

Release date:

- 28 September 2023

-

FULL TRANSCRIPT

Roots of resilience: on the front lines of climate justice

Episode 3: The land is not for sale, it is to be loved, to be defended

INTRODUCTION: Welcome. You are listening to Roots of Resilience, a podcast of the global collision for forests. So, there is a crisis that is increasingly stronger, more worrying and let’s say, in light of the fact that the solutions offered by the system are false solutions and are not working to reverse these environmental and climate crises.

VALENTINA FIGUERA MARTINEZ: Hello everyone. My name is Valentina Figuera Martínez.

I greet you from Brazil. Welcome to Roots of Resilience, Global Forest Coalition Podcast.

Greetings to the people who are listening to us. Today we are with Diego Cardona Calle, coordinator of the Forests and Biodiversity area of Sensat. Living Water from Colombia. Diego is an environmentalist, forestry engineer and master in Tropical Forest Sciences.

He is also co-founder of the Forest and Biodiversity area of Agua Viva, a researcher on community management of forests and territories, deforestation, green and financial economy, and the realization of nature.

He was president of the Global Forest Coalition between 2015 and 2020 and is also the current regional co-coordinator of the Forests and Biodiversity Program of Friends of the Earth International.

Diego has also worked in research to corroborate the contribution of family and traditional agriculture to the conservation of soils and biodiversity in the Colombian Andes and the Brazilian Amazon.

We are also with Camila Romero, socio-environmental activist and defender of the Viento Sur collective from Chile. Camila is also a campaign coordinator and collaborator in community projects for environmental, territorial defense and the rights of indigenous peoples.

Camila is also a researcher in Sociocultural Anthropology at the Universidad Austral de Chile and we are also accompanied by Omar Jean Pay Omar is a sociologist and candidate for the Master’s Degree in Sociology and Political Science at the National University of Asunción in Paraguay and a professor and researcher at the Center for Studies in today.

Omar is a founding member of the Paraguayan Association of Sociology and a member of the Socio-Territorial Movements Working Group in Critical and Comparative Perspective of the Latin American Center for Social Sciences. Clacso Welcome, welcome. Thanks for joining us.

I would like to ask Camila some questions, start with her and well, everyone feel free to enter this conversation. Camila, I would like to know your opinion on the different initiatives and funds instruments to access both national bilateral and multilateral financing sources to support the implementation of the global biological diversity framework. No. That historic agreement that was signed last year, not in Montreal, and that governs everything that has to do with the matter of biological diversity. And well, I wanted to know what the barriers and opportunities that women have to access the resources necessary to develop collective protection actions.

CAMILA ROMERO:Well, thank you very much, Valentina. Greet all those who are listening to the colleagues also present here. Today I am in the Los Ríos region, in the Valdivia area.

From here we are activating both at a local, territorial and international level, making connection precisely with the territorial struggles that we also experience in Latin America, with these spaces for discussion that occur at a global level.

Well, to maybe comment something else. In particular, the issue of what it is like for the communities of indigenous peoples and especially for women, to be able to have access to these funds and these instruments as well. And we realize that there are many barriers starting from access to information and technological means to be able to remain, to be able to reach, A, to, to have this access, eh, to the procedures.

That is a barrier that is particularly faced in many indigenous communities due to the characteristics of inhabiting a territory that has historically faced inequalities within the framework of this system. And precisely today, when we go to these spaces, we realize that there are more and more towns.

There are more and more ancestral indigenous nationalities that are arriving to be able to break this gap that exists and also having results in their, in their joints, eh? Strengthening, especially when there are demands that are being brought and that also come back to the territories.

So perhaps to mention that a little, the opportunities we have are empowerment and strengthening leadership, also the representation that can be had in these mechanisms and participation. We believe that, we believe that it is important to improve access to participation in consultation and starting from these mechanisms that are moving towards the conservation of biodiversity and that particularly affects indigenous territories.

VALENTINA: Yes, thank you, Camila, Very interesting. In short, one of the, let’s say, of the big changes when this is accessed, that question of greater participation is something fundamental, no. And that is also why the importance, precisely, of reflecting on and defending, not the importance of these initiatives and these funds really reaching where they have to go, which are the indigenous communities and especially the non-indigenous women who are in the first front line, truly consolidating traditional protection mechanisms.

I am very interested in knowing what experiences you know from Chile about resource mobilization towards women that have had good conservation results. What happens when resources do arrive for women? Forests that are fighting against monocultures, for example, which is an area that you work a lot?

CAMILA: And of course, of course it is important to highlight positive aspects that we are having some results that, although not so great, since we are faced with a forest extractivist model that is quite large and has impacts internally, then, within Perhaps some of the progress that is being made is precisely to improve a little the issue of participation and strengthening leadership. And this is essential for the defense of forests.

In other words, strengthening the leadership of women, who are the main defenders of forests, of waters, of nature itself is also to advance in a movement, a local movement, a global movement.

And that is happening today, which is what I applaud and I find that it is very positive to be able to see more women from communities, women, indigenous people and young people who are also participating, who are working in community programs that are breaking these gaps. that we mentioned previously. That’s a very positive thing. As I said, the forestry industry is a model that puts pressure on many territories that have been colonized, territories historically crossed by a colonial conflict, eh? Without a doubt, community strengthening is positive due to the years of colonization and fragmentation that has occurred within the communities.

VALENTINA: Thank you Camila, I don’t know if from Colombia, Diego or from Paraguay or Mar want to tell us something similar, or maybe if it is another, let’s say, experience that they can share in relation to when the resources arrive, not from these multilateral funds .

DIEGO CARDONA: And in the Colombian case, unfortunately what one finds is a situation that is quite negative in this regard in the majority of territories, for example, in the Amazon, where at this moment the large funds, multilateral investment programs or some programs. Large bilateral programs between, for example, the Colombian Government and some other states.

Well, what one finds is that they share them in the knowledge that these large financing projects exist. But there is no change in the environmental reality in the territory, nor resources that can show that they are arriving and that impact, let’s say, the life of the communities or their rights or the environmental crisis that they express.

Rather there is a claim and and a of. How then do these resources reach the country and in some way, or stay at the central level, in the capital, in Bogotá or in offices or somewhere, but they do not reach the territories or the communities.

And it is something, let’s say that one can find reiterated in many territories, when, uh, when you go to them and talk to the communities.

VALENTINA: Already very interesting because it is something that we have also read from other realities. Omar also happens like this in Paraguay or is it something a little more different from reality?

OMAR YAMPEY: I believe that the communities, that is, the grassroots groups, do not receive the funds, the resources, which is a problem in general, at least in Paraguay, between self-management, the art of autonomy, which is agency their ways of coping with the general situation, right?

VALENTINA: I would like to ask you precisely what you see or consider to be the link between the colonization of the Via Ayala of our territories and the current logic of capitalist exploitation of the forests? What has changed and what do you think remains the same since then?

CAMILA: Well, unfortunately, our Latin American territory continues to be understood since colonization, eh? Mm, But the ancestral peoples, eh MM have maintained a memory, they have maintained systems that are not the current ones or systems of knowledge, systems of relationship also with, especially with nature. And that bond, that relationship has been broken with colonization. And, well, extractivism is also a way of relating to nature and it is also talked about among ourselves. There are concepts that refer to anthological extractivism. Even then both concepts go hand in hand. Both experiences are, are, are united.

Colonization is sustained by extractivism, by the plundering of our territories, and the construction of the societies in which we live today is sustained by it. And why also talk about the exploitation of women’s bodies. I mean, we are now talking a little more about that.

Some time ago our grandmothers, our mothers, did not talk about it and now we are waking up and I hope that there are more of us because it is not enough. May it also be the male brothers who also have to change a way of relating to each other. And that is what extractivism is telling us. That’s what nature on earth is telling us.

VALENTINA: Yes, it is interesting that whole connection that you establish, not about colonization and patriarchy, because well, we were formed from a little of that, not from that holocaust that there was, that destroyed our people and really, from there we begin. to model different ways of being, of seeing, of being a man, of being a woman, not of existing and I think it is also nice to build those dialogues and think about what we want to build new and well, I think that is why we are here too to just enter and build new possibilities. New reflections Diego, I would like to ask you, how do you see the current state of the climate and biodiversity crisis?

DIEGO: Well, the balance that one can make at the moment is unfortunately not positive. If one looks at different sources of information, we see how I don’t know the reports, for example from IPE. We see how entire populations of plants and animals are being lost at an increasingly accelerated rate throughout the planet, but in a more accentuated or more reserved way here, in our region, in Abia Ayala we are not talking now it is like, let’s say, We are losing an amount of natural heritage at an impressive rate.

And that, obviously, has repercussions on the ecological crisis, not the heritage that is lost if we are to look, for example, at the quantity of seeds or varieties of breeds on which the feeding of animals depends. all human beings.

On this planet we have also lost an impressive amount of variety seeds, no, which is becoming increasingly simpler. The way we feed ourselves depends more on commodified supply chains. So, let’s say, we no longer eat hundreds of varieties of potatoes that we had or have.

Not, for example, in the countries of the Andean region, here in America, but we eat a few that are arranged, let’s say, as if by the food systems. The same thing happens with rice, with corn, non-transgenic or manipulated or concentrated, let’s say, in a few hands, especially let’s say, from houses that handle the sale of seeds, not or the technological packages for cultivation or management. of some the breeding of some animals.

On the one hand, in climate terms we also observe how the expressions of climate change are also becoming more and more noticeable, not only, let’s say, from what one sees by talking to the communities, with the people in their territories, but also from the evidence that oneself can have.

VALENTINA: Yes, and it is also the differentiated aspect towards women. No, because it is precisely on women’s bodies that a large part of their impacts also fall in a differentiated and specific way, so, as we say, culturally responsible for sustaining life? No?

This series of expressions that translate into everyday life, from irregular harvesting to water collection and seed preservation, has a very strong impact on women. And I am sure that you, from your different territories, have been able to do it, you have been able to do it. notice and but from the point of view of positive community practices, Diego, that they are implementing in Colombia, that you are following from the different territories where you move, indigenous peoples and local communities. What are those positive community practices that you see from Colombia?

And also if colleagues Camila from Chile and Omar from Paraguay could also tell us about positive practices, especially for women. Do you see?

DIEGO: Well, in the case of S Sensat, one of the initiatives, not the alternative proposals that we demand, that we try to support, that there is recognition is precisely the community management of forests and territories, that is, what communities and peoples in their territories.

It has been many years, millennia or centuries, to be able to be there, but using the natural heritage they have. And one can find here multiple expressions of that community management. For example, indigenous peoples in which, let’s say their territories in which they live in the jungle, have lower levels of deforestation or degradation than, for example, with official protected areas such as parks, national parks or we see the case of Afro-descendant communities, in which around the level of degradation of monocultures is highly, therefore not degrading or harmful.

And in those communities or in those specific territories where the communities are organized to manage it in a different way, we find higher levels of biodiversity, higher crops in an agroecological system, for example, levels of forest coverage, but also very high organizational levels. strong, not in terms, for example, of other communities that have, let’s say, social conditions, access to education, to some services, such as transportation, that are much more diminished.

In these other organized communities when there is community management, we find different conditions, for example, also in the case in the northeast of the country, with the Collective of Peasant and Community Reserves of Santander, in which the women are Let’s say, those that have the initiative, for example, in their territories to make agroecology real.

But not only with a small family practice, on a very localized scale on their farms, but there are also community reserves, areas in which the communities, let’s say, understand the common good beyond what is on their farm, but Let’s say, how to preserve, not or protect, let’s say, an entire area with a series of functions that can be fulfilled, let’s say, in water regulation in access to water, since it benefits an entire community and that becomes a reality without there being need neither government intervention nor external projects.

No, it is not the green economy projects or payment for environmental services that are strengthening these conditions, but rather the initiative and work of the communities themselves in their territories.

VALENTINA: What have you encountered and what are the women of those communities you visit like, what are their strengths?

DIEGO: Without a doubt I would have to mention, for example, peasant families on which we have very, very special pressure in which, for example, they preserve more than eighty-four varieties of more than eighty-four varieties of beans and a similar amount of potato varieties, while in the country not here in Colombia, while in the market we only now have four, maximum five varieties of potatoes available.

It also impresses me, for example, when I go to places like Santander, where the reservation group is located and in a very difficult environment, let’s say, in territories occupied by monocultures, as in the case of Lebrija. All surrounded by a pineapple monoculture with soils supremely degraded by the monoculture. One finds the initiatives of women with community provisions, recovering the soil and recovering their farms to not have a mind, have water, have biodiversity and see that this is reality.

I am not impressed, for example, to see beyond the discourse that says that the common good is not possible. That is to say, the only way in which people protect is if they have a piece of land or something of private property. And when you go and find a community reservation, which is not the position of any of the people, of any of the families in particular, but of all of them.

So I am impressed by the way in which local communities overthrow so many paradigms that the market and the way of generating knowledge that looks at schools, let’s say European or American, as the referents, those referents that tell us that they can only be achieved through private property, privatization, private property, it is possible to protect and it is possible to manage.

And the communities show us that it is not possible to do it together, among all, guaranteeing rights and living in a different way, not in one way, a good life or a tasty life, a way different from what they want to impose on us.

VALENTINA: I would like to ask you to go a little bit towards a topic that, well, I think is fundamental, which is climate funds and you have had good experience on this topic. As a researcher, I would also like to ask you what are the problematic aspects of one of the international climate funds, like the “Green Climate Fund” for example, tell the people who are listening to us, what those funds are, what is being financed and what impacts they bring, especially for indigenous women and local communities.

OMAR: Well, I believe that these funds, at least in particular the green climate fund, agree with the true diagnosis, with the diagnosis that we propose, just as our colleague from Colombia, Diego, proposed, that emissions must be reduced. greenhouse gases and combat climate change, the diagnosis of these funds and the United Nations Framework Convention and the Paris Agreement, let’s say it is correct.

Now, the problem is the method to solve this problem of the climate crisis. And that’s where all this deployment of false solutions comes in. Yes, and I believe that the problem is in the method of resolving this situation and also what the agents are. Here there is a lot of emphasis on companies and not on peasant and indigenous communities and those who really have the capacity to resolve and respond as an alternative and overcome this current situation of climate crisis, which is also here.

We, with engineers, always discuss this, not the climate crisis as a natural issue, but there is also an economic dimension here. There are economic interests. There is a dimension of transnational, regional, local political power that makes the destruction of nature a precondition for accumulating greater profits. That is a precondition for this economic model to persist and also the displacement of indigenous peasant communities, because for this economic advance they are a true obstacle and every obstacle must be destroyed.

So, the agents of these funds, let’s say, are not placed in the indigenous peasant communities as an alternative, but again. There are companies, local holding companies, right? And this, what led us to the debacle and the climate crisis, is proposed as a solution. That is, one more twist to the extractive model. Everything is everything we say in Paraguay, a forestry business.

We have been seeing cycles of dispossession and destruction of the colony’s environment to this day, but from the nineties to this point we saw the entry of transgenic soybeans, livestock, and today, which we believe is the devil’s circle, Milton Santos would say. , is the plantation of eucalyptus as a supposed solution to the climate crisis that in reality what it comes to do is to exacerbate this extraction model. And in the case of this green climate fund, it was born back in two thousand and ten.

What we said was the mandate of the United Nations Framework Convention to help sub-global countries counteract the impacts of climate change in Paraguay. In Paraguay and other African countries they financed or are financing the Avaro Verdad fund, with twenty-five million dollars for the planting of seventy-five thousand hectares of eucalyptus trees, etc.

And very recently, last month, the And Green Verdad Fund was created, created by the IMF, the Dutch bank, to also plant monocultures of oil palm, cocoa, rubber, etc. This was in eleven countries and also six in Africa. What we say and what we also see with other colleagues is that this is a little more the extraction model, but with good speeches. Yes, there is a lot of emphasis on marketing and speech.

With this idea that they are coming to solve the problem of the climate crisis, then it is more complex to dismantle, because the discourse and the resources they put into marketing in the communities generates attention. And we are seeing this in each of the spaces where investment is made in this sense, right? in the situation in which the indigenous peasant community finds itself. For example, in the Paraguayan case of an economic crisis and the peasant agriculture model, they offer jobs.

They come with a speech that they offer jobs, that they are going to provide a solution to climate change, that they are going to give promises of development to the communities. But when contrasted in the territories it is quite the opposite, right? This idea of maximizing profits continues, but it is difficult to dismantle because they are generating consensus in the communities. The situation in which the indigenous peasant community finds itself seems to be an economic solution.

In the case of a greedy fund that invests in two agroforestry companies in the department of San Pedro, the community says given the situation we are in, they offer us a job. So they have no choice but to gradually become attached to this model. There they are dismantling the community capacities of resistance.

They are dismantling the very perspective of food sovereignty that they have truth because they do not invest in the projects of indigenous peasant communities. If they have ecological and social responsibility, as their foundations suggest, they allocate that money. Those amounts for authentic projects for subjects who, in their way of producing and reproducing as beings linked to nature, are the alternative in reality, not in discourse or marketing, right?

VALENTINA: I wanted to ask you in relation to those alternatives that you mention, what experiences with Graco technologies or family, peasant or indigenous agriculture? You can highlight us from Paraguay, Genio. The GEI Studies Center does not have very interesting work in that sense and I would like to know which communities are promoting AGROECOLOGY as an alternative to industrial agriculture.

OMAR: Yes, we see in recent times, with great hope, that despite, let’s say, the blows received by the indigenous peasant communities, there is a will to begin to articulate towards a more national-scale project, because that is the key. .

There is a problem of scale in Paraguay, there are experiences, everything that is fragmented. There are extraordinary efforts by women, mainly as the normative companion of a peasant organization that produced, let’s say, in a traditional way. Then his family got sick. As a result of that, she entered, became aware and today she is one of the multipliers of the ecological agriculture model, right?

There are peasant, indigenous, urban experiences, a great effort that has also been genius and to connect rural producers, male and female producers and consumers in the city. There is an awareness. There is a meeting in the actions, also joint. So let’s say that there are interesting, important efforts, but they need, let’s say, a higher scale and articulation.

There is the case of The Maidana producer, who has about twenty types of corn at the annual fairs that GE organizes today with seed producers. There is great diversity there. There is a great demonstration of potential not only as an alternative to climate change and eco-systemic destruction, but it is also profitable.

It is profitable when it is produced in an agroecological way, not only as a model of life, as a model of life and in addition to that, it also generates income and people can live by producing in an agroecological way, because normally the discourse of agrobusiness is that agroecology does not profitable, etc. However, there are experiences that show that this connection between production, consumer, fair market, equitable price, fair debate can work.

The challenge is the scale, yes, the scale and behind this not only a will to live, but also a political will to articulate towards forms, towards respect for these diversities, for these forms of production, but also towards a form superior to this current system. And we see this specifically in recent years, after centuries of being separate and going their separate ways, Indigenous peasant communities are meeting in debates, they are meeting in the streets, in mobilizations, they are exchanging knowledge and knowledge and That is new for the political history of Paraguay and probably also for the future.

VALENTINA: Thanks Omar. Thank you Diego, for your time and for your willingness, for having shared with us your experiences in the different territories. Thanks also to Camila and And I also wanted to ask you both to close briefly, eh?

About the Yes to Yasuní no consultation, through which, well, the Ecuadorian people voted in favor of not exploring exploiting oil in the Ecuadorian Amazon and we saw that the consultation extended, not beyond the scope of activism for justice environmental, and moved on to a much broader scope and I wanted to ask you, consulting about preserving life on the planet is a democratic act of strengthening environmental awareness, or rather it evidences the illegal ethical inability to protect the jungles and biodiversity.

This should really be consulted, isn’t it something quite obvious that how do you see it? How do they perceive it?

DIEGO: Well, Valentina, no. It doesn’t seem so obvious to me. I think it’s something like it happens, as with common sense it is the least common of all the senses. We would hope that life in all its manifestations was not something that was the responsibility of everyone. That it was something palpable, that it was something that was not even in discussion, not in analysis, it should be protected from being maintained happily. We know that’s not the case, right?

So, beyond the fact that the duty is the duty to be, of course the preservation of life should be, that the territories, the rights of the people, that those who inhabit them should be above economic interest. In this case, like that of those who exploit oil and profit from it. Faced with all the impact that the Yasuri territory has had.

Not after times, years and years of impactful oil exploitation, no, but I think it would also be necessary to see it, let’s say, from another perspective. And it is the perspective of how we say the demands. The fights for defense, let’s say territorial, for the defense of the life of the jungles, of the people, of the jungles, well, they become valid.

It is not that they can override all rights, it is not that they can override all territories. It is not that all the things that happen every day in many places on the planet can happen just like that there. I believe that the result of the social process in Ecuador that leads to that vote that should have also taken place ten years ago.

But it was a process that was postponed, that was there as in time, dormant, as if then it had already passed into oblivion and no one else is going to cut it ten years after that. Well, it doesn’t show that it is there, that people continue to mobilize, that there is interest in defending life and well, let’s say, from that, perhaps from that perspective, because it seems important to me to claim that we can organize, that we can defend our rights. and that it is important to continue doing.

OMAR: I would like to add something to what Diego said, which I kept thinking about when you asked the question and I think it is a bit complicated for me to think that we make things available to some circumstantial majorities that should be the monopoly of the people and the nation. .

That is to say, this is complicated for me because depending on the situation there are times when there are certain majorities, it happens in Chile. To give an example, if now in Argentina we start to democratize, if the State is demolished, the majority will probably win. If it is defined that mining has to advance, probably today a majority will advance on that. So I think there are things that in a society superior to this one would not have to be discussed. That is to say, natural resources should be the monopoly of indigenous peoples and peasants and do not have to be made available to a political debate.

Let’s say the truth, but that comes in a draft because I did not follow the case much, but it is a little complicated for me to think about making resources or means available for a vote or that they should be a monopoly of the people. I think the Mexican case is very interesting there, the forests, the waters, etc.

They are property not of the State, but of the nation, of the people that exist and live in Mexico. So I think there are things that are not debatable. They shouldn’t be

VALENTINA: Of course.

What I was asking was precisely as a provocation. No? Of course, what Diego mentions is extremely important. Not in terms of the political mobilization generated by the Yes to Yasuní consultation and the demonstration of political muscle and intervention in spaces that go beyond socio-environmental activism, which is fundamental.

Also because many times we are like talking to each other and listening to each other. And there is a difficulty in expanding those voices towards other realities that are, ultimately, different, not and often opposite. And it is precisely important, of course, that mobilization and that correlation of forces that was generated.

But I was wondering, well, I was really wondering, that is, how can we be consulting or not consulting something that seems so obvious and so necessary today? No, of course we all celebrated and there would be no way not to celebrate that the consultation was favorable. And we also hope and we will be. We will continue to favor and support the struggles from different perspectives, from different spaces.

And well, also happy because Because well, because it was a way to demonstrate and unite and and and consolidate something that, well, which is very necessary, but well, I did it from that place of provocation more than anything, thanks to all the people who You heard us today on the Roots of Resilience Podcast from the Global Forest Coalition.

Thanks also to Camila Romero, from the Viento Sur collective in Chile, Diego Cardona, from Sensat Agua Viva in Colombia, and Omar Jean Pai, from the Ño Studies Center in Paraguay, for sharing their experiences, knowledge, and wisdom from their different perspectives. territories. We invite you to follow this podcast on different platforms and follow our collective work on Instagram. We are at Arroba Global do Forest and well, see you next time.

Chao how