Indigenous Peoples, Afro-descendants, and peasant farmers resist “green deserts” in Brazil

By the Global Forest Coalition

On International Day Against Monoculture Tree Plantations we bring you this photo-essay showing the devastation caused by monoculture tree plantations in Brazil, and in contrast, community efforts to restore native forests and build sustainable livelihoods.

We focus on the northeastern Brazilian states of Bahia and Espirito Santo, where eucalyptus plantations cover as much as 70% of the land area in some municipalities, having replaced the Atlantic Forest ecosystem which is endemic to the region. The plantations are run by Suzano, Fibria and Veracel, some of the most powerful players in the global pulp industry. Their eucalyptus is mostly exported internationally as pulp, to produce consumer paper products such as toilet paper.

Eucalyptus is an exotic species of tree endemic only to parts of Australia, but today it dominates tree plantations around the world. Brazil is now the world’s top exporter and producer of eucalyptus round wood and pulp.

Eucalyptus plantations in Brazil are ecologically very harmful as they suck up huge quantities of water, support a very low diversity of flora and fauna, and require high pesticide and fertilizer use. Unlike native forests, they disrupt the hydrological cycle, severely reduce biodiversity, and don’t produce food. Locals call these plantations “green deserts”, as they are devoid of life.

Photo by Simone Lovera

Originally, the entire region was covered in biodiversity-rich, native Atlantic Forest, a subtropical rainforest. Today, over 92% of it has been lost through land conversion to monoculture tree plantations, vast soy fields for animal feedstock, and extensive cattle ranching.

Ironically, replanting deforested areas with eucalyptus counts as “reforestation”, and has given the industry further opportunities for expansion. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization has supported this type of fake “reforestation” as a false solution to climate change.

Photo by Simone Lovera

The state of Bahia is one of the worst affected by eucalyptus plantations in Brazil. All together, Fibria, Suzano and Veracel own almost 1 million ha of land in the state. 60% of this is eucalyptus plantation. The three corporations are very closely linked: Suzano and Fibria recently merged to become a global pulp giant, which in turn owns half of Veracel.

These companies claim to play a key role in conserving forest remnants, and by law 20% of their land should be conserved as a “legal reserve”. But the companies meet this target by designating land that is too steep to be economically profitable as reserves, whilst covering the rest in plantations.

Photo by Simone Lovera

Deforestation and land conversion on such as scale has created serious conflict with and problems for local communities.

In spite of claims made by the industry that they are providing jobs for local people, the reality is that plantations and ranching provide barely any employment at all for local communities. Plantations in the region typically provide less than one job per 100 ha of land, which is the lowest of all of the crops grown.

Photo by Simone Lovera

In stark contrast to this is an agroecological farm in the same area, run by Movimento Sem Terra (MST, Landless Workers’ Movement), which provides 5-10 times more jobs per hectare of land than the surrounding plantations. The MST is one of the largest social movements in Latin America, and has been fighting against the concentration of land ownership into the hands of the few. Land occupations are one of the key direct-action tactics used by the MST.

The MST reclaimed the land pictured here from the plantation owners, and created this agroecological farm as a training school and community project. It was part of a series of actions to apply political pressure, including protests and land occupations. Today, the farm grows 120 different tree and plant species on its agricultural plots, which provide food and sustenance for local communities.

Photo by Simone Lovera

Women have played a central role in the campaigns, land occupations and the establishment of the agro-ecological school. Here, Elione Oliveira, one of the coordinators of the Egidio Brunetto Agroecology School established by the MST, explains how they are fighting back against the expansion of eucalyptus plantations.

Women have made critical links between patriarchy and plantations. Elione explains that when they occupy eucalyptus plantations, they spend a significant part of the day debating about patriarchy, problems with monocultures, aerial agro-toxic spraying, land ownership, and why all of this is important for women.

Photo by Ines Franchescelli

The Tupiniquim are indigenous to the area and have been supported by many international and national NGOs in their 20 year struggle against the Aracruz plantation company (now Fibria/Suzano). They have succeeded in reclaiming 18,070 ha of land, for the 3500 people in their community, but they are still suffering the impacts of the surrounding eucalyptus plantations, which have led to a lack of water and pollution from agrochemicals. They are also still struggling to remove eucalyptus trees from their land, which have to be dug up by the roots.

Photo by Simone Lovera

The Coxi Quilombera community is surrounded by Fibria plantations. Quilombos are hinterland settlements founded by Afro-descendents, and the small community pictured here is led by seven sisters.

A high percentage of community members suffer from glaucoma, which has been scientifically linked to poisoning from exposure to glyphosate, a chemical used on the plantations. Water courses that used to provide the community with fish and freshwater have dried up, and the company has also blocked access to the Quilombola communities only source of fuelwood, which consisted of unused leftovers from the wood harvest.

Photo by Simone Lovera

Plantation companies claim to plant primarily on “degraded lands”, but land formerly used for cattle ranching and other agricultural uses in the Atlantic Forest area have significant restorative capacity. Up to 60% of these lands can be restored naturally, without human intervention, if set aside. But once they are planted with eucalyptus, it is almost impossible to restore the original forest cover. Eucalyptus trees are allelopathic, which prevents other tree species from becoming established, and the impact on water resources and pollution from agro-toxics reduces biodiversity further, and destroys soil fertility.

Photo by Simone Lovera

Pictured here is a “reforestation” effort with barely any undergrowth because the area has been heavily sprayed with glyphosate. Companies like Suzano are legally required to reforest some areas. In order to do this, they use significant amounts of glyphosate to remove existing vegetation before planting, as this is cheaper than doing it manually.

On a national level, the Brazilian Climate Plan includes an afforestation target of 13 million hectares of land, of which only 15% has to be with native species. Suzano has already received hundreds of thousands of Euros through a forest carbon offset scheme for these “restoration” activities. But even when areas are planted with native trees, these schemes only cause more harm.

Photo by Simone Lovera

A more positive state intervention is the Arboretum Program, set up by the Bahia State Government to promote forest restoration with native trees. It is central to efforts to restore the Atlantic Forest through community forest restoration. Here, staff at the Arboretum Center are showing native tree leaves to colleagues. The centre collects and disseminates a wide variety of native trees, and encourages communities to collect native seed varieties, exchange them, and plant trees. It works with a network of community centres throughout the region.

Photo by Simone Lovera

Wherever there are eucalyptus plantations, the consequences for local people and biodiversity are devastating, from across South America, to Southern Africa, Southern Europe and even Australia. But in all of these places communities are fighting back, and trying to undo the harm done by restoring forests themselves.

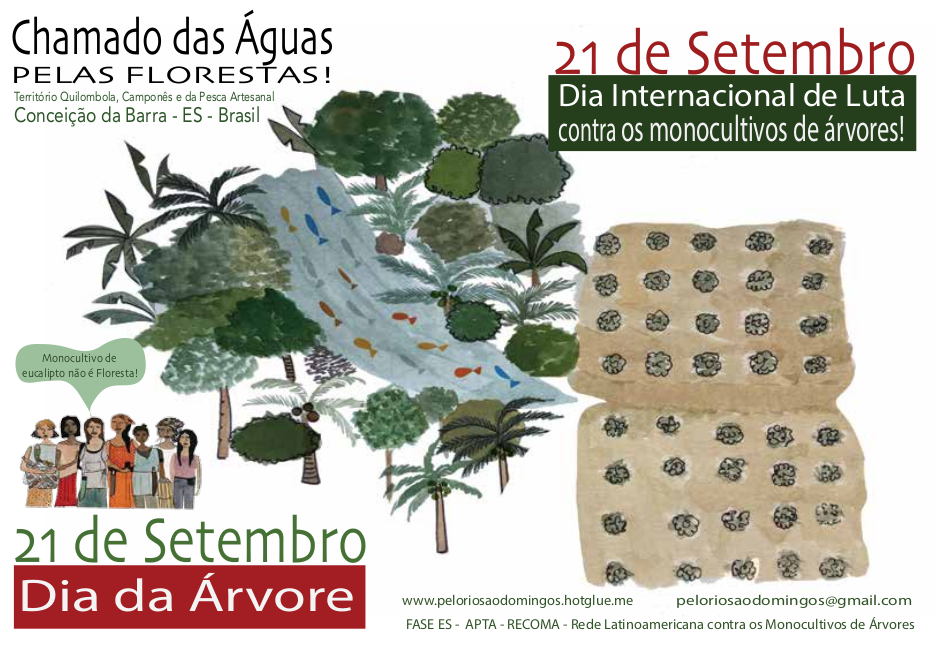

Our member group in Brazil, FASE, have been actively campaigning against monoculture plantations for decades. On the 21 September they will highlight the severe water shortages caused by commercial eucalyptus plantations in Espirito Santo. They have collected evidence and testimonies of environmental crimes that Fibria/Suzano have carried out, and are organising with fishermen, landless workers, and Quilombolo communities to expose these companies. You can find out more about their other activities here here.

Poster by FASE