Download the summary report here

by Tesfaye Tolla and Cath Traynor

INTRODUCTION

The Bale Mountains, in the Oromia Region of southeast Ethiopia are a biodiversity hotspot. For generations, local communities in this area have stewarded their natural resources through Sacred Natural Sites (SNS). SNS are biologically diverse natural cultural centres where local communities gather to help one another, resolve conflicts, establish common law, and worship. They represent deep spiritual relationships between communities and nature. Communities from the kebeles [A kebele is the smallest administrative unit of Ethiopia and refers to a well-defined collection of settlements or villages.] of Dinsho-02, Mio and Abakera, in Dinsho District assessed the roles and resilience of SNS for community conservation in and around The Bale Mountain National Park.

The CCRI assessment utilised participatory mapping to determine the location, area and biophysical aspects of both existing and destroyed SNS in the area. Typically located on hills or knolls, the SNS contain a range of biophysical features including springs, streams, wetlands, indigenous forests and wild animals. The majority of SNS lie outside the boundary of Bale Mountain National Park and receive no formal government protection.

Historically inhabited by seasonal pastoralists, the government has encouraged permanent settlement and intensive agricultural production in this area since the 1990s. The population has steadily increased and today the main livelihood is agro-pastoralism with farmers cultivating a variety of grains and legumes as well as rearing cattle and sheep. Approximately 90% of the land is allocated to individuals with remaining land areas classified as forest or communal lands. SNS are not formally recognised under Ethiopian law and fall under the forest or communal land category.

COMMUNITY CONSERVATION RESILIENCE IN ETHIOPIA

The CCRI used participatory mapping, spatial data collection, focal group discussions, and semi-structured interviews to examine both biophysical aspects and threats to SNS. 26% of the participants were women. The assessment, within the three kebeles, revealed that historically there were 72 SNS. However, over the last 50 years 54 SNS had been destroyed and only 18 currently remain. SNS have been governed by custodians and elders for many generations and play a key role in enhancing the communities’ spiritual connection to nature.

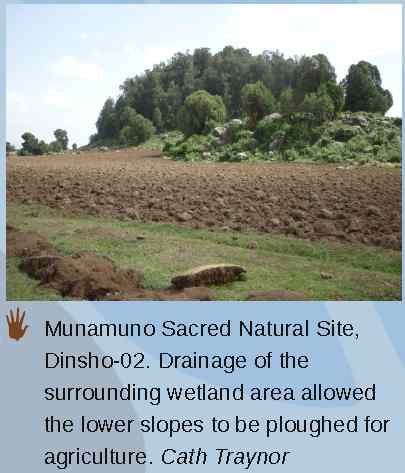

Key internal threats centre on community perceptions and attitudes. Many community members failed to understand the true meaning and value of SNS. Some have sought to undermine and marginalise SNS custodians. The land allocation system within the kebeles, which allows SNS land to be allocated to individuals for farming, has resulted in the destruction of SNS. Furthermore, SNS have been converted to agricultural land and wetlands have been drained. Land shortages have also pushed some religious faiths to begin to use SNS as burial grounds, which threatens their integrity.

A significant external threat is the lack of formal recognition or protection for SNS within Ethiopian law. SNS are not recognised in Ethiopia’s legal framework and the contribution they make to biodiversity, conservation, ecosystem services provision, and the nation’s cultural heritage is not acknowledged. Globalisation, modernisation and acculturation also threaten SNS. The traditional knowledge systems that gave rise to SNS and the customs and traditions that maintain them are often regarded as backward.

PRELIMINARY CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Community-initiated solutions include the raising of awareness within the community regarding the value and significance of SNS. The CCRI has already produced some successful examples of SNS conservation that can be used as models. For example, in Mio kebele, a fence was built around the Gedebgela SNS. As a result, there has been a reduction of incursions onto the site and harvesting pressures. Peer-to-peer learning exchanges between communities are required so that these successful approaches can be shared and adapted.[ Teshuma Abera, Community member from Mio kabele]

To counter internal threats the capacity of SNS custodians should be enhanced to enable them to fulfil their roles and responsibilities. Additionally, a SNS elders group should be formed to revive customary laws, norms and ethics regarding SNS and to develop new by-laws for the conservation of SNS.

To counter external threats existing conservation legislation, cultural heritage policies, and relevant articles in Ethiopia’s 1995[ Articles 39(2), 44, 51(5), 90, and 91] constitution that support SNS need to be enforced. However, these mechanisms do not specifically target SNS and are insufficient to ensure their full protection. Therefore, a national level policy that addresses SNS is required. International human rights and environmental laws that recognise the value of SNS and the roles of custodians and communities in conservation should be harnessed.[ For example, the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) Articles 8(j) and 10(c) and the: Akwė: Kon Voluntary Guidelines]

Preliminary recommendations from the assessment include a range of initiatives. First, create a network between the SNS custodians from different communities with quarterly meetings to plan community-led strategies and activities for SNS conservation. Additionally, scale-up the assessment to include other kebeles in Dinsho District and the Bale Zone. Communities also need financial and technical support to manage SNS; for example, fencing initiatives and reforestation efforts. Finally, advocacy is needed at all levels within the Cultural and Tourism Office, Rural Land Administrative and Environmental Protection Office and the Bale Mountain National Park authorities. All of these initiatives will strengthen community conservation and resilience in the area and need support from outside actors.

TESTIMONY

After the assessment, which showed the loss of SNSs in the area, the community was pained to see what they have lost, and now we have to consider how to conserve and ensure the sustainability of the remaining SNS for the future. The assessment reminds us of the legacy of the past 12 generations, and now we are starting to revive the conservation activities that they practiced. The assessment was a wake-up-call, and each of us saw what we had lost.

– Adam Haddijasso, Dinsho-02 kebele

Download Report of the Community Conservation Resilience Initiative in Ethiopia here.