Community Conservation Resilience Initiative in Russia

Download the summary report here

Introduction

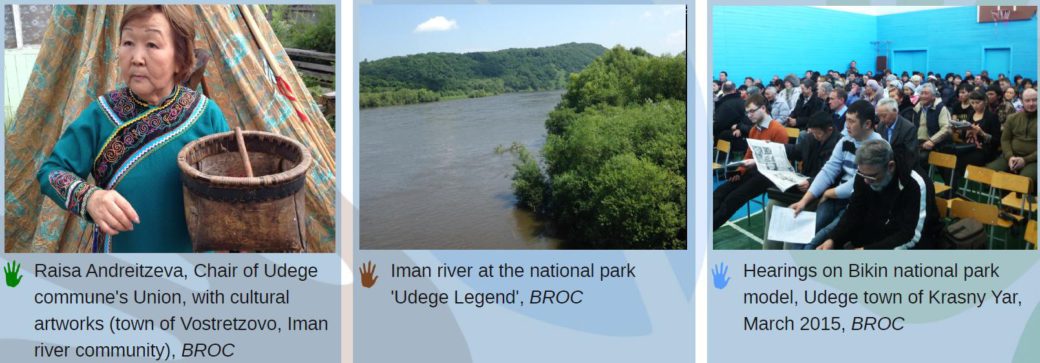

The Udege, one of the 48 indigenous peoples in Russia, inhabit the Ussuri taiga in the SikhoteAlin mountain range. This area contains the highest biodiversity in boreal Asia, including the Siberian tiger and other rare species of fauna and flora. [1] The Udege in the Primorye region are united through roughly twenty legal entities called obschina (tribal communes).

Women have equal rights to men and play a significant role in dealing with officials, regulations and documents. They tend to be much more aware of legal details and specific problems of fish and wildlife use and management and often fulfil leadership positions in communes and associations.

Udege traditional areas face the rapid expansion of external logging, hunting, salmon fishing and mining operations. [1] As such, the Udege suffer from competition over the resources that sustain their livelihoods. Russian law formally recognises the existence of indigenous territories and grants native peoples special hunting and fishing rights. [3] [4] However, there is a serious discrepancy between formal rights, law enforcement and management practices, leading to deep conflicts around indigenous priorities. Regulations regarding indigenous privileges are overly complicated, unclear, and often changed without informing the communities.

The CCRI worked with three Udege communities in Primorye inhabiting the Iman, Bikin and Samarga river valleys consisting of several legal communes with distinct conditions. The assessment process included regular bilateral contacts with community leaders, field visits, and a round table discussion with indigenous leaders and the Deputy Governor, which led to the adoption of a road map. A fullday capacity building workshop for leaders of the three communities took place at the Iman municipal centre.

Community conservation resilience in Russia

The main external threats identified by the communities include the absence of recognised land rights and the overexploitation of fish and wildlife resources by poachers, especially the overharvesting of salmon stocks by commercial fishing fleets, which has led to a serious decline in salmon resources. Government authorities often react by limiting hunting and fishing opportunities for the Udege, who already lack natural resources. Social and political marginalisation, and not understanding the regulations, trigger frequent conflicts between communes and government inspectors, turning Udege into criminal poachers and prey for inspectors. [5]

Legal and illegal logging forms another serious threat for the livelihoods of Udege communities. Specific threats to the Samarga and Bikin community include bad infrastructure, which made it hard for them to bring nontimber forest products (NTFP) and salmon to the market. The ‘Udege Legend’ National Park was created on the Iman River to support Udege culture and

livelihoods. However timber businesses, dependent local officials and hunters succeeded in replacing an Udege friendly person with a former inspector for the director’s position. As a result Udege people themselves are now banned from entering the park, which is seriously harming their traditional hunting practices.

The main internal threats identified include the lack of capacity to fully understand relevant hunting and fishing regulations. This leads to frequent conflicts, both with law enforcement authorities and internally, as indigenous and nonindigenous individuals in one community are subject to different privileges. Another serious threat is the loss of traditional knowledge, language and customary practices, especially amongst the youth. Moreover, many young people choose to stay in cities after completing their education, causing a generational gap. Due to lack of employment and opportunities, there are few people between the ages of twenty and thirty in traditional communities.

Preliminary conclusions and recommendations

At the meeting in May 2015, the Deputy Governor and Udege communities agreed on a roadmap for future work and progress. CCRI meeting participants generally confirmed the roadmap in July 2015. The roadmap included a range of initiatives and goals. First, to pass regional regulations with indigenous participation, providing prioritised access to justified volumes of fish and wildlife resources for indigenous communities. Additionally, to regularly monitor the environmental conditions in indigenous territories. Thirdly, to support the selfgovernance of communities through the creation of indigenous councils under the regional and municipal governments of Primorye. Furthermore, to address the main social problems in the communities including education, medical services, power supply and infrastructure.

In addition to this, the community initiated further recommendations to support community resilience and conservation. Recommendations include strengthening policies and strategies to prevent overexploitation of salmon stocks and including indigenous representatives in working groups that establish fish and wildlife quotas. There is also a need to address illegal and unsustainable logging and create special rules to cut Korean pine for Udege traditional boats and wood for tribal needs. There should be a training programme for young Udege on traditional resource management practices and related skills that contribute to economic livelihoods. They also called for the creation of the Bikin National Park as a comanaged protected area with effective indigenous participation and the correction of federal legislation; and to recreate the indigenous division in the Udege Legend National Park and ensure its management complies with the law. Communities need to be educated about current regulations in fishing and hunting, and governmental agencies need to properly recognise, respect and support indigenous conservation practices, traditional knowledge and related privileges.

Testimony

“Russian law formally acknowledges the existence of indigenous territories, but in practice no specific territory has been recognised. Indigenous peoples live there, can hunt and fish, but they have no tenure at all. Our experience collaborating with national parks authorities caused low trust in that model of conservation, until our rights to take part in territorial

“Russian law formally acknowledges the existence of indigenous territories, but in practice no specific territory has been recognised. Indigenous peoples live there, can hunt and fish, but they have no tenure at all. Our experience collaborating with national parks authorities caused low trust in that model of conservation, until our rights to take part in territorial

management are legally granted. We hope the new Bikin Park will do this for all national parks. There should also be an indigenous fund for protection of traditional knowledge and culture with an indigenous council under a federal programme.” Nadezhda Selyuk, Vice Chair of the Primorye Association of Indigenous People. Photo: Nadezhda Selyuk, BROC

Download Report of the Community Conservation Resilience Initiative in Russia here.

References

[1] Gorovoy et al. 2004. Biodiversity of the Far Eastern Ecoregion Complex. Vladivostok: WWF, www.wwf.ru/data/publ/1100.pdf.

[2] Pacific Environment, 2014. Conservation Investment Strategy for the Russian Far East, www.pacificenvironment.org. Accessed 31 July

2015.

[3] Russian Ministry of Natural Resources and Ecology, 2010. Hunting Regulations in the Russian Federation. http://www.nexplorer.ru/pravila_ohoty.html, Accessed 31 July 2015.

[4] Order of the Russian Ministry of Agriculture, 2006. Adoption of the fishing rules to provide subsistence of traditional resource use for indigenous people of Russia, www.docs.cntd.ru/document/901972341. Accessed 31 July 2015.

[5] WWFRussia, 2009. Problems of Russian Protected Areas Legislation: Analytic Review and Recommendations. Мoscow,

www.wwf.ru/resources/publ/book/319. Accessed 31 July 2015.