From Baku to Belém

An Uphill Struggle for Climate Justice

GFC’s Souparna Lahiri and others address the media at a press conference at COP29, Baku, Azerbaijan, November 2024.

By Souparna Lahiri

In the early hours of 24 November 2024, the United Nations Climate Change Conference, COP 29 in Baku, ended in a controversial and bizarre manner. A weak decision on the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG)—a global finance target to help poorer nations cope with the impacts of climate change—was gavelled through without providing Parties any opportunity to deliver their statements. This action by the Azerbaijan Presidency sparked outrage. India, supported by Bolivia, Cuba, and Nigeria, strongly opposed the undemocratic process and stated that the NCQG text, which calls for the mobilization of $300 billion by developed countries by 2035, is insufficient and unacceptable.

I first attended the UN Climate Change Conference in 2002 in New Delhi—that was COP 8. As we look now towards COP 30 in Belém, Brazil, I’m not sure if I’ve ever felt so disappointed by the UNFCCC process.

Cuba, Bolivia, and Nigeria highlighted issues of environmental colonialization and neo-colonialism, describing the current international regime as unequal, unfair, and exclusionary. India went further, branding the NCQG deal an “optical illusion”.

As I sat, tired after two weeks in Baku, watching the final plenary play out like a scene from a disaster movie, I reflected on my many years engaging with the Conference of the Parties (COP) process. I first attended the UN Climate Change Conference in 2002 in New Delhi—that was COP 8. As we look now towards COP 30 in Belém, Brazil, I’m not sure if I’ve ever felt so disappointed by the UNFCCC—the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change—process.

In that final plenary, my misgivings were reflected by many. Indigenous Peoples’ organisations slammed the COP process as unethical and the NCQG as a product of a sham process. In an impassioned speech, Youngo—the official children and youth constituency of the UNFCCC—accused the COP Presidency of collusion with fossil fuel lobbies responsible for funding genocide and wars, and of promoting carbon markets and an exclusionary and discriminatory process. There was no mincing of words when it came to the NCQG agreement itself: “This deal, it kills the Paris Agreement,” they declared.

The widening North-South divide, increasing lack of consensus, and a diminishing recognition of the principles of Common But Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capabilities (CBDR-RC)—a cornerstone of the Rio Declaration and the very basis of Climate Justice—are indications that the multilateral climate regime is failing.

The Women and Gender Constituency, Climate Action Network, Trade Unions and the Demand Climate Justice coalition chose not to deliver statements in the closing plenary, refusing to lend legitimacy to what they termed a failure in process. Under the Azerbaijan Presidency, the Conference of the Parties had been turned into a “conference of developed countries,” they told the Plenary: “We refuse to bring more legitimacy to a system that has collectively failed all of us for the benefit of a few.”

A Rude Beginning

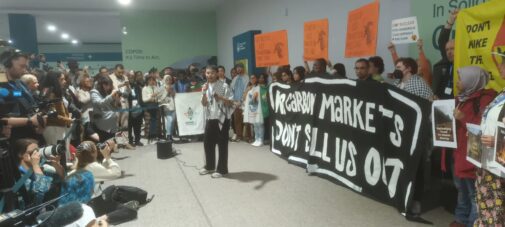

Protesters at COP 29 in Baku call for an end to carbon markets and other false climate solutions.

This controversial and bizarre conclusion to COP 29 was foreshadowed by an equally problematic start. On November 11, the opening day of COP 29, the Presidency unilaterally gavelled through the adoption of standards by the Supervisory Body of Article 6.4 of the Paris Agreement, promoting carbon offsets and carbon trading, without providing any opportunity to the Parties to review them. This complete break from procedure undermined the Conference of Parties to the Paris Agreement (CMA). But none objected, except Tuvalu, who expressed deep concern at the “procedural lapse”.

The widening North-South divide, increasing lack of consensus, and a diminishing recognition of the principles of Common But Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capabilities (CBDR-RC)—a cornerstone of the Rio Declaration and the very basis of Climate Justice—are indications that the multilateral climate regime is failing.

Decisions that are required to address the planet’s most pressing crisis are increasingly being driven by stifling legitimate voices, where “forced” compromises by the vulnerable and most affected are misrepresented as “consensus”.

Shrinking Spaces for Climate Justice

The UN-backed climate regime has become increasingly hostile to civil society. Iconic climate justice marches are no longer allowed by successive and authoritarian COP presidencies, and civil society spaces are shrinking. Inside actions and protests are being dehumanised. Within the conference halls and corridors of the UNFCCC, human rights, the rights of Indigenous Peoples, women and local communities, even just the mention of them, or workers, peasants, and farmers, or gender justice, are being made controversial, hushed and hidden as if they are profanities.

Pathways to the Paris Agreement’s goal of limiting global warming to 1.5°C remains elusive. Trading in mitigation outcome and offset credits will not reduce global emissions; negotiations on the Global Stocktake (GST) under the UAE Dialogue is deadlocked, the all-important discussions on Just Transition remain stalled, and with the revised Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) due by February 2025, the lack of adequate climate finance to support conditional NDCs threatens to undermine ambitions. We are now just five years away from the critical 2030 milestone.

Looking to Belém

Hope and optimism in the multilateral process have always led us to believe in the next year, and the next COP. Despite COP 29’s failures, there is yet cautious optimism for COP 30 in Belém under the Brazilian Presidency. However, Brazil’s track record still raises concerns.

Brazil was supportive of the decisions taken by the COP 29 Presidency, including the NCQG deal. It has consistently backed the transition of the Clean Development Mechanism and the carbon market under the Paris Agreement. Brazil is also a front-runner in adopting many of the false solutions to climate change, such as monoculture plantations, REDD+, forest carbon offset projects, and voluntary carbon markets.

Though the road to Belém will undoubtedly be a difficult and uphill struggle for climate justice, this grassroots confluence of peoples and an autonomous mobilisation offers hope.

A prominent supporter of biofuels, bioenergy, and the bioeconomy, Brazil is also one of the world’s top fossil fuel exporters, exporting three times more oil and gas than Azarbaijan, according to BloombergNEF. Under its G20 Presidency, one of the working groups also adopted nature-based solutions, which GFC and others have consistently criticised as a dangerous barrier to resolving the climate and biodiversity crises.

The Rio G20 Declaration includes mobilising finance including climate finance from all sources—multilateral banks, blended and innovative finance, private finance and other financial mechanisms. While the Amazon continues to burn and deforestation continues, Brazil is proposing a tropical forest finance facility built on market-driven principles, that provides investor returns for conservation and protection of forests.

Protesters at COP 29 call for genuine solutions ahead of COP 30.

A Glimmer of Hope

Amid these challenges, Brazilian social movements and civil society organizations are mobilising to organize the Peoples’ Summit towards COP 30 as a parallel space to the UN’s COP 30. In the context of a climate crisis that fosters inequalities and injustice, this autonomous initiative aims to strengthen democracy, confront the extreme right, expose false climate solutions, and demand real commitments to combat climate change with effective policies to protect the territorial rights of Indigenous Peoples and traditional communities and a just transition.

Though the road to Belém will undoubtedly be a difficult and uphill struggle for climate justice, this grassroots confluence of peoples and an autonomous mobilisation offers hope. By amplifying the voices of the climate-vulnerable and most affected, the People’s Summit could yet pave the way for a rights-based, gender-just, and ecosystem-centered pathway to climate justice.

Souparna Lahiri is the Global Forest Coalition’s Senior Policy Advisor on Climate and Biodiversity