Download the summary report here

INTRODUCTION

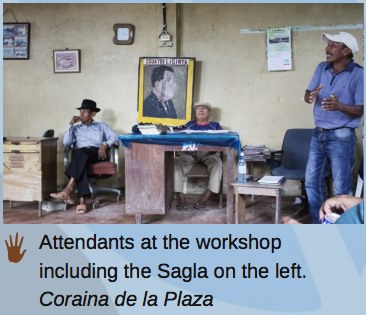

The two-day workshop took place on Ustupu island, in the Guna Yala Indigenous Region. People from various Guna communities participated, most of whom live on small, scattered islands. It was attended by a diverse range of community members including the ‘Saglas’ (community chiefs), the administrative chief, members of the Guna women’s committee, and members of a local NGO.

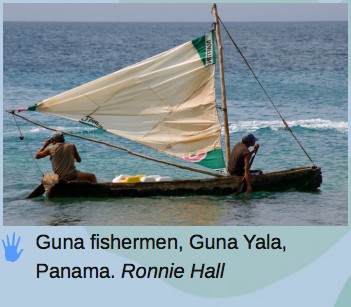

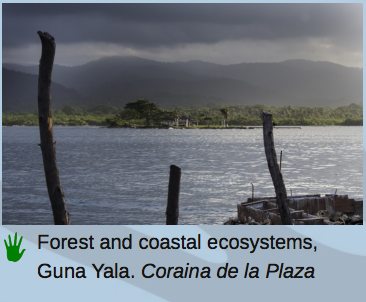

The main types of ecosystem in the region are tropical rainforests, mangroves and coastal marine ecosystems. The region is highly biodiverse, having, for instance, more than 150 species of mammal.[1] The Guna people depend primarily upon the mainland forests and mangroves near the islands, which provide, among other things, food, medicine and materials to build their houses. In addition, the sea constitutes an important source of protein.

One of the key ways in which the Gunas have protected their forests is by having sacred areas, which are mainly primary forest, combined with rotating agriculture or ‘Nainu’, usually in the lowland areas. There are different types of Nainu agricultural systems but the main characteristic is to plant useful trees together with other vegetable species.[2]

The situation of the Gunas is quite unique. They enjoy what is probably one of the highest degrees of self-governance and autonomy among the Indigenous Peoples of Latin America. After the Guna revolution, which took place in 1925, the Panamanian government agreed to establish the Guna Yala Indigenous Region, as established in the ‘Ley Fundamental Guna’.[3] They are thus are in charge of the management of their own l territories on the basis of their customary law and traditional rights.[4] They have a well organised and structured political body and decision-making processes. Political decisions are taken within the communities in assemblies and then the Saglas speak on behalf of their community.

COMMUNITY CONSERVATION RESILIENCE IN GUNA YALA

During the workshop, all attendants were able to express their views about the main threats to Guna habitat and resources, and the resilience embedded in their practices. They voiced particular concern about cultural erosion, mainly among young people. This process was identified as being very disruptive in the application of traditional knowledge to ecosystem management, production methods and subsistence activities.

This threat is partly external, because of Western influence in the surroundings areas and within the Guna Yala Region. In addition to this, when young people want to pursue higher education, they have to leave the community. When they return they are often disinclined to live according to the Guna traditional way. But it is also an internal threat because families have placed less emphasis on teaching Guna culture to the children. The key consequences of this cultural erosion are the gradual loss of knowledge about the forests and traditional agriculture, and the advent of consumerism, creating waste and garbage. All participants were determined to correct this trend as soon as possible.

PRELIMINARY CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

For the Gunas it is vital to preserve these mainland forests, for their own sake but also for the survival of future generations and Guna culture. To overcome the weakening of Guna identity, culture and practices, several proposals were made for a strategy to strengthen the resilience of Guna conservation activities. These included the creation of a school to teach Guna traditions, excursions with the children to the mainland forests, and the establishment of a pilot plot.

It was agreed that activities to strengthen the Guna Yala CCRI should be very practical. They decided to focus on establishing a pilot plot. The idea is to locate it near to the shore where some species that are commonly used for food production, medicine, etc., can be found and/or planted, and to teach the children how to identify species and understand their importance. They can also learn about the traditional management systems, and spend time in the forest to reinforce their link with nature.

The biological impact of this initiative is evident. Once the children learn about the forests, the equilibrium within them and the way in which the Gunas depend on and relate to nature, they will be inspired to preserve and use the resources sustainably, as their elders do. This will also help to reduce their involvement in consumerism and have a positive impact on biodiversity generally. Community members committed to ensuring the continuity and success of this initiative. They appreciated support so far, welcomed assistance in identifying donors, and invited further visits to see the progress they have made.

TESTIMONY

The women emphasised how much everything has changed. Hermecia Kantule explained that when she was young, women had to wake up early and start knitting their Molas (women’s traditional clothes[5]). Afterwards, they would prepare breakfast and take care of the house. Sometimes they would help bring back products from the forests with the men. Women are key for the transmission of traditional knowledge since they spend more time with the children. Her mother taught her to identify different useful species, but children are not learning these things now. She supported the idea of creating a space where children can learn and revive traditional knowledge and Guna culture.

Download Report of the Community Conservation Resilience Initiative in Panama here.

[1] Chaplin M, 2000. Defending Kuna Yala: PEMASKY, the Study Project for the Management of the Wildlands of Kuna Yala, Panama, Mac Chaplin, http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNACM974.pdf

[2] FAO, undated. “Nainu” agriculture: an alternative for the management of natural forests, Panama, accessed 4.8.2015, http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/esw/esw_new/documents/SARD/good_practices_Latin_America/13_Nainu_agriculture_Panama1.pdf

[3] Congreso General de la Cultura Kuna, Ley Fundamental y Estatuto de Kuna Yala Relacionados al Congreso General de la Cultura Kuna, accessed 4.8.2015, http://onmaked.nativeweb.org/ley_fundamental_y_estatuto_de_ku.htm

[4] Marks D, 2014. The Kuna Mola: Dress, Politics and Cultural Survival, Maney Online Vol 40, Issue 1 (May 2015), pp17-30, accessed 28.6.2015, http://www.maneyonline.com/doi/abs/10.1179/0361211214Z.00000000021

[5] Marks D, 2014. The Kuna Mola: Dress, Politics and Cultural Survival, Maney Online Vol 40, Issue 1 (May 2015), pp17-30, accessed 28.6.2015, http://www.maneyonline.com/doi/abs/10.1179/0361211214Z.00000000021