Trade in genetic resources

Case study: Bioprospecting in Costa Rica

Case study: Bioprospecting in Costa Rica

Resources

Bioprospecting is a form of commodification of natural resources that is intended to create economic benefits whilst conserving those resources.

The concept was developed in the 1980s, notably by US Professors Eisner and Janzen. They proposed a system through which countries that were genetically rich but economically under-developed could capitalize on their natural wealth by offering companies from rich countries access to their genetic resources. These companies would then use their technology to develop marketable products, and secure intellectual property rights to their ‘inventions’ through the use of patents.

Bioprospecting fits with a world vision that is currently in vogue: that we can only conserve and care for what is understood and has a value.

This approach is now underpinning a business that creates millions of dollars for a handful of companies, who take advantage of the cultural knowledge of those Indigenous and local communities responsible for the conservation, use and improvement of biodiversity, based on collective practices.

For these people there are no benefits. The process is having a negative impact on Indigenous Peoples, creating conflict within and between communities and eroding their culture of sharing.

Nevertheless, within the framework of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), many governments and other institutions are currently promoting a market-oriented approach to benefit sharing. They favor a system in which individual governments, communities and/or institutions can sell their genetic resources and related traditional knowledge on a commercial basis.

The CBD’s voluntary Bonn Guidelines on Access and Benefit Sharing, which were adopted in 2002, basically foster a bilateral system of gene trade (although they could be interpreted as supporting a multilateral system too). However, only five months after these Guidelines were adopted, a group of developing countries effectively overturned them, by having the World Summit on Sustainable Development adopt a recommendation that an ‘international regime on benefit sharing’ was to be ‘negotiated’.

Those negotiations continue even now; and the question of whether they address access and benefit-sharing, or just access, is still contested.

At its ninth meeting in Bonn, in May 2008, governments negotiating in the CBD reiterated their instruction to the CBD’s Working Group on Access and Benefit Sharing to complete the elaboration and negotiation of the international regime at the earliest possible time before the tenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties in 2010.

Meanwhile, the relationship between these negotiations and ongoing related negotiations within the framework of the Food and Agriculture Organization’s Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources, the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) and the World Trade Organization (WTO) are uncertain. The relationship is even less clear now that negotiations in the WTO, generally a very powerful and influential organization, are stalled. The question is whether the collapse of WTO negotiations would create a renewed opportunity for a less trade-oriented and more publicly governed system of access and benefit sharing.

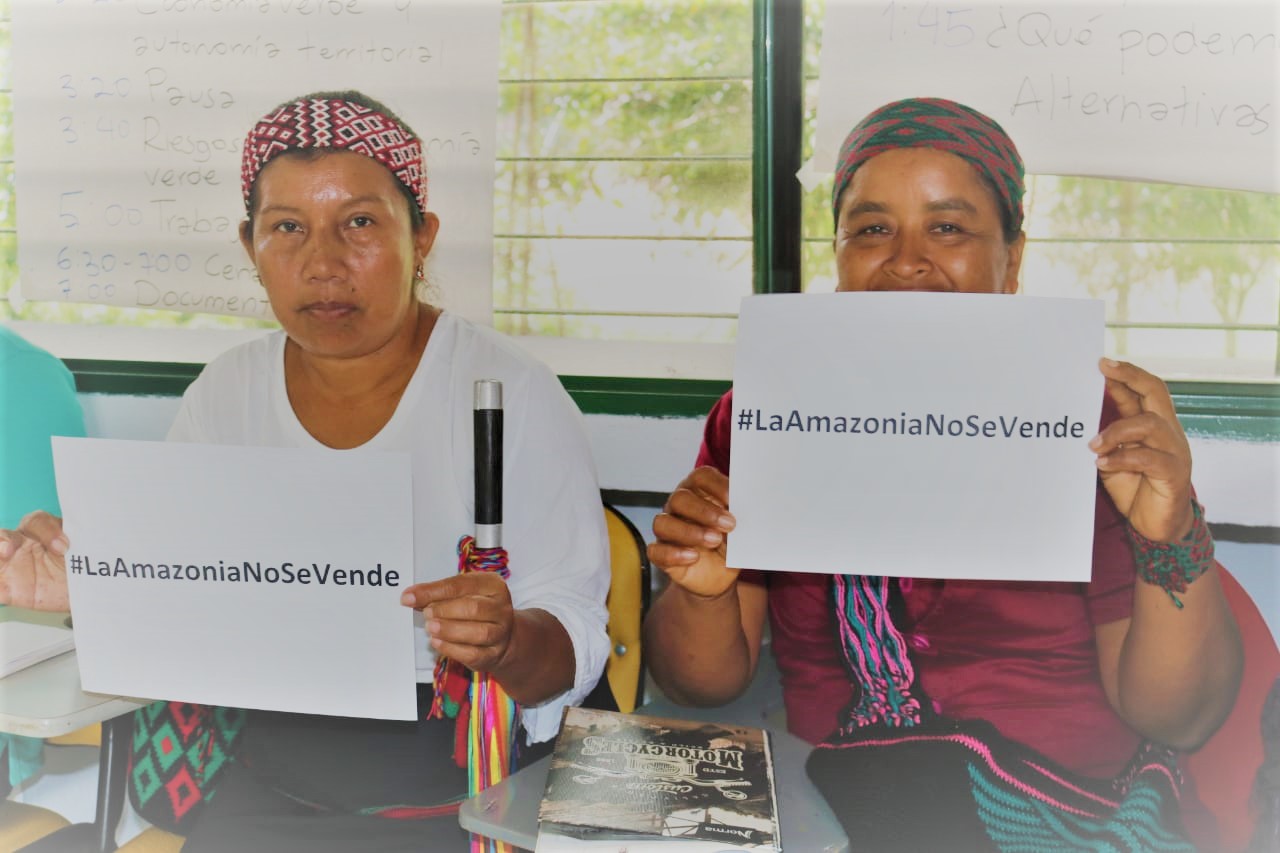

Indigenous Peoples have time and time again voiced their concern that the current negotiations within the framework of the CBD squarely ignore their rights over their own territories and traditional knowledge, especially in relation to access and benefit sharing.

These rights have been reconfirmed by the UN Declaration on Indigenous Peoples, an instrument that should certainly be seen as an inherent component of the international regime on access and benefit sharing. Nevertheless, a small number of governments that are signatories to the CBD refuse to recognize the Declaration.

Please refer to Life as Commerce: how market-based conservation impact on community governance for summary case study or the full report on Bioprospecting in Costa Rica.