Continuez à lire en anglais…

We’re also hosting a webinar later today (Monday 21st September, 10am Santiago de Chile/3pm Amsterdam/6:30pm Delhi) where our member groups will present examples from the report of these impacts and also how women’s rights groups and other civil society organisations are working to overcome them through protest and gender-responsive, community-led alternatives to the tree plantation model. To participate, please register here. The webinar will be held in English with interpretation in Spanish and French.

Download the report in English (web quality 9MB | low resolution 1.3MB), y en español (web quality | low resolution).

Contents:

Introduction

Quilombola women resisting eucalyptus plantations in Brazil

The impacts of palm oil plantations on community livelihoods and women on Bugala Island, Uganda

West Papua: Depths of loss and heights of resistance

Eucalyptus monocultures: The green cancer plaguing rural women in Paraguay

The impacts of tree plantations and forced evictions on Indigenous women in Gorkha municipality, Nepal

Forest protection and women’s rights must go hand-in-hand in Rwanda

Confronting the impacts of the plantation forestry model in Chile

Resistance, autonomy and reclaiming forests: how Baiga women transformed a marginalised Indigenous community in India

Industrial forestry versus wetlands in an Argentina in flames: Environmental defenders to the rescue of diverse and dissident nature

Conclusion

Towards the sustainability of life

Introduction

By Johanna Molina, Colectivo VientoSur and GFC board member for Latin America and the Caribbean, and Jeanette Sequeira, Global Forest Coalition, Netherlands

Considering the systemic crisis that humanity is facing, it is a fact that Western society has organised itself “in contradiction to the basic materials that sustain life”1 through the exploitation of nature and the appropriation of human labour—and particularly women’s labour. This is not to ensure the common good, but rather, capital accumulation in the hands of a few.

This anthropocentric, patriarchal and colonialist worldview leads us to view the planet as if it had no limits, to put nature and common goods exclusively at our service, and to assign some people more value than others, justifying policies of natural resource extraction and dispossession that have various impacts on territories, peoples and communities, and particularly on women. In this context, “capitalist society expands like a tumour at the expense of destroying what we truly need”2 to reproduce life—both human and non-human.

The forestry industry has been one of the drivers of the commodification of nature and the privatisation of common goods globally. The model of large-scale monoculture tree plantations (mostly exotic species) has led to the destruction of native forests and agricultural lands, and with it evictions of primarily peasant and Indigenous communities, justified by the false solutions promoted by international policies on forests and climate. These false solutions treat such plantations as carbon sinks, but as we know, they have failed to address the problems of deforestation, climate change and other environmental harm that they are supposed to solve. Worse still, plantations are poor carbon sinks especially when compared to native forests, and often release far more carbon than the trees temporarily reabsorb.

At the root of the problem is the fact that the definition of forests used by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) still includes plantations, which are now called “planted forests”, equating a diverse and complex ecosystem with a single species cash crop that by design excludes biodiversity. For the forestry industry and policy-makers, this false equivalence is highly advantageous, since wood is a valuable commodity both for whatever its intended use is (such as supermarket packaging, charcoal or wood pellets) and for the fact that the carbon in plantations can be easily calculated and traded, adding more value.

For this reason, climate mitigation and corporate social responsibility strategies aiming towards negative or “net-zero” emissions, or Nature-Based Solutions, as well as global ecosystem restoration initiatives such as the Bonn Challenge,3 New York Declaration on Forests and African Forest Landscape Restoration Initiative (AFR100), have all turned their attention to reforestation and afforestation with tree plantations. International climate finance has done the same, led by private-sector pursuit of profit and a mitigation strategy that profits from each harvest. Recent examples of this include the Global Environment Facility’s finance of eucalyptus plantation projects in Brazil4 and Uganda5 for charcoal production, and the Green Climate Fund’s support for the Arbaro Fund,6 which will use public money to create an additional 75,000 hectares of mainly eucalyptus plantations in Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa.

Bioenergy is another driver of plantation expansion that is also closely tied to climate mitigation strategies. Due to flaws in the way that carbon is accounted for, wood from commodified supply chains such as tree plantations is considered renewable and therefore the carbon released when it is burned is simply ignored. This means that energy generated from burning wood, whether as charcoal or wood pellets, counts as renewable, low-carbon energy and can be subsidised with lucrative government contracts. Bioenergy is also driving hugely destructive palm oil plantations, which is likely to be boosted further if plans for the aviation industry to burn biofuels are rolled-out.7

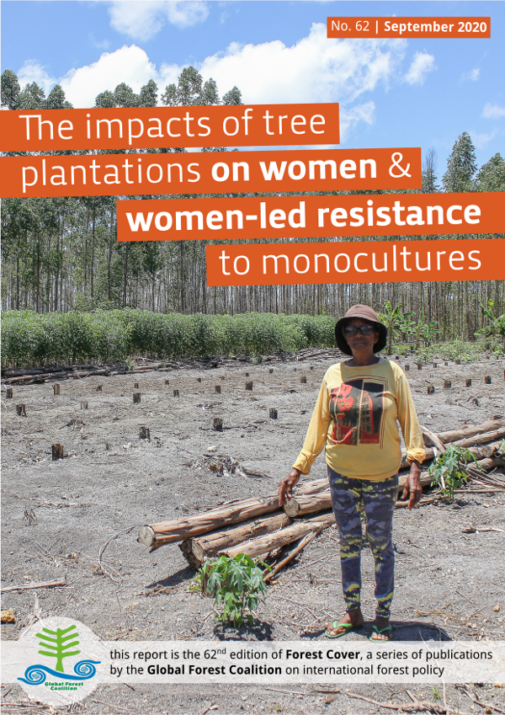

This situation of rapidly expanding plantations has had serious consequences for communities, and particularly women, for they are the ones who traditionally sustain life and culture. Water scarcity, the loss of biodiversity and traditional medicines, pollution, erosion, higher incidence of mega-fires, the invasion of community lands, occupation of sacred spaces and forced displacements are just some of the impacts jeopardizing the survival, sovereignty and cultural practices of peoples.

Whilst some of these impacts are well-documented, less attention is given to the gender-differentiated impacts of tree plantations. Greater analysis and action on the issue is needed, and this publication aims to contribute to this by amplifying the voices and struggles of women in nine countries. In the first section, Global Forest Coalition member groups explore the impacts of plantations on women in Brazil, Uganda, Paraguay, Nepal, Rwanda and West Papua, whilst in the second section, stories from Argentina, Chile and India describe powerful woman-led and community resistance to this nefarious industry. Finally, a concluding section sets out the action that must be taken to protect women and communities from the threats posed by ever-expanding commercial monocultures.

1 Herrero, Y. (2014). “Economía ecológica y economía feminista: un diálogo necesario” [Feminist economics and ecological economics, the necessary and urgent dialogue]. In Cristina Carrasco, ed., Con voz propia. La economía feminista como apuesta teórica y política. Madrid, Viento Sur, 2014. https://vientosur.info/wp-content/uploads/spip/pdf/con_voz_propia.pdf

2 Ibid.

3 A recent study revealed how almost half of the area in government pledges under the Bonn Challenge so far will become commercial tree plantations: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-01026-8

4 See Global Forest Coalition’s investigation into GEF’s project in Brazil: https://globalforestcoalition.org/brazil-charcoal-case-study/

5 See Global Forest Coalition’s investigation into GEF’s project in Uganda: https://globalforestcoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/uganda-GEF-case-study.pdf

6 See https://globalforestcoalition.org/gcf-arbaro-fund/

7 See https://globalforestcoalition.org/132-civil-society-organisations-critizise-corsia-in-open-letter-to-icao-council/

Quilombola women resisting eucalyptus plantations in Brazil

By Daniela Meirelles, FASE/ES, Brazil

Quilombola1 women from Sapê do Norte in the state of Espírito Santo in southeastern Brazil are warriors; guardians of nature; farmers; story-tellers; religious and community leaders; representatives of municipal, state and national movements; public workers; health workers; teachers; students; healers and dancers who, each in their own way, face oppression, violence and exclusion.

In this article, we will be talking specifically about conflicts with Suzano S.A. (a merger between Fibria, formerly Aracruz Celulose, and Suzano Papel e Celulose), the world’s largest pulp producer. In Espírito Santo, the company has three pulp factories in the municipality of Aracruz (built on Indigenous Tupiniquim villages) and one port (Portocel, in partnership with Cenibra), and it recently announced the construction of a new toilet paper factory in the south of the state. On top of this, it has thousands of hectares of its own eucalyptus plantations and other plantation areas it manages. Since the company began operating in the 1960s, the different shareholders controlling the company and government administrations of varying political stripes have come and gone, but the aim of this aggressive, industrial (chemical) plantations project has remained the same: expansion at any cost and without limits.

In Conceição da Barra alone, Suzano controls 62% of the municipality (with 53,000 hectares of eucalyptus) and plans to expand by another 5,000 hectares. It is disrespecting a municipal law that mandates a gradual reduction in total plantation area to 20% of the municipality, and through the courts (which until now have always been on the company’s side) has forced an environmental licensing process with a virtual “public hearing” amid the coronavirus pandemic.

In the northern region of Espírito Santo, Suzano has inherited significant socioenvironmental “liabilities”, which are the result of conflicts that have been dealt with through violence, oppression and exploitation. These methods are also characteristic of the patriarchal and sexist society that created this model of development and is common to all of the plantation and pulp companies that operate in the region.

With constant State support, the company strategy has been to intimidate the approximately 12,000 quilombola families that inhabited Sapê do Norte (a region comprising the municipalities of São Mateus and Conceição da Barra), deceiving them with the promise of better living conditions, invading their rich Atlantic Forest ecosystem and destroying houses, farmland and forests in the process.

Women, as always, have been the most impacted, particularly Black women. Those that were expelled from their land had to survive in the urban peripheries, often in humiliating living and working conditions. Those that managed to stay experienced all of the destruction and mutilation firsthand. Surrounded by vast eucalyptus plantations; far from their relatives; deprived of access to true forests; prevented from worshiping at their sacred forest sites; and unable to provide for their own material, nutritional, medicinal and cultural needs, a radical transformation that was violently imposed on them. Even if the company had tried, no amount could compensate for such drastic losses over so many generations.

Without remuneration or due recognition of the valuable work that they have been delegated (domestic, health care and education), this exploitation of women goes along with the expansion of capital over borders. In this case, the overburdening of women and gender inequalities are symptoms of the dictatorship of capital. Many men left to look for work abroad (since the promises of employment in the plantations were never really true) and the quantity and quality of land and water decreased substantially (today the region is considered semiarid), compromising the food and nutritional security of families.

With the widespread use of herbicides and pesticides by the company in its plantations (some, such as glyphosate, are now banned in several countries), health conditions have worsened greatly. It is common, for example, to hear reports of women with fibroid tumours. With the closure of many rural schools, education shifted from being in and about the countryside to being in and about the city, forcing children to travel to urban areas on dangerous roads and transport.

When quilombola communities and women demanded jobs in the plantations, they were offered work applying pesticides in very unsafe conditions and with the company refusing to assume any of the risks associated with the work. When they tried to educate their children based on their traditional knowledge, collectively planting native seedlings and crops, the company sprayed pesticides indiscriminately, destroying what they had planted. When they cultivated oil palms as part of their ancestral rituals and medicinal practices, the company and the authorities argued that they were the ones growing exotic trees. When they were awarded a contract to sell food to the local school meal programme, the authorities discriminated against them and rejected their produce. When they tried to restore springs that the company has destroyed, the authorities demanded a management plan from them.

Despite all of this, and without free, prior and informed consent or the legal recognition of their lands, the unconquerable and ancestral strength of women has driven their desire to remain on and reclaim their lands, fight for gender equality and their rights, and defend life.

Eternal gratitude to these women who light the way.

1 Quilombolas are residents of quilombo settlements first established by escaped slaves in Brazil.

The impacts of palm oil plantations on community livelihoods and women on Bugala Island, Uganda

by Kureeba David, NAPE, and Betty Nanyonjo Kabaalu, Kalangala Women and Youth Development Association (KAWOYDA), Uganda

Twenty-three years ago, the Government of Uganda launched a project to increase domestic production of vegetable oils through commercial palm oil plantations. Beginning in 2006, the project planted around 10,000 hectares of oil palms on Bugala Island in Kalangala district, in Lake Victoria in partnership with the private sector and with the support of the United Nations International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) and World Bank.1

The project had a devastating impact on the environment, with an estimated 3,600 hectares of forests and biodiverse wetlands being destroyed to make way for the palm oil plantations.2 Meanwhile, land grabbing associated with the project left communities impoverished, unable to grow food and without access to income. Women were hit particularly hard and lacked the option to move to other islands in search of other means of survival. Therefore, five years ago, NAPE/Friends of the Earth Uganda took the company responsible to court in a public interest litigation case in support of families who lost their land to the palm oil plantations on Bugala Island. The case is ongoing, but NAPE and other civil society organisations also petitioned the World Bank’s ombudsman,3 and some farmers have since been compensated, although others refused the compensation offered as they claimed it was insufficient.

Before the introduction of palm oil, the island’s population of around 20,000 people, of which around 5,000 were women, mainly depended on subsistence farming, tourism and fishing—the latter traditionally employs predominantly men, hence the large difference in numbers of men and women. Women on the island generated income through fish smoking and farming,4 but the introduction of palm oil resulted in some communities—and particularly women—being pushed off their farmland, losing access to food and income. Grazing was severely affected as livestock were excluded from plantation areas.5 About 100 families in Kalangala lost their land to the palm oil plantations.6

Women on Bugala Island were affected by the plantations in three main ways. First, whether through landgrabbing or consent by a male head of household, their ability to farm and earn an income from the land was reduced as agricultural land was given over to oil palms. Second, women’s extremely low levels of land ownership and political representation excluded them from decision-making and any potential benefits from the plantations. Third, the were discriminated against in the work they were able to access in the plantations.

Women in Uganda endure a ‘triple work burden’ that is unpaid and undervalued by society. They are largely responsible for domestic, farming and community work, which includes the vital role of ensuring that families are fed.7 Women are central to agricultural production and maintaining food security in Uganda, but the introduction of palm oil plantations in Bugala stripped them of their original livelihood activity of farming.

Patriarchal and traditional community gender roles, particularly around customary land tenure, give women access to land only with consent from their clans or husbands. Thus, about 16% of Ugandan women own land, despite the fact that they perform 76% of the agricultural work. Only about 7% of the land owned by women is registered,8 meaning that the vast majority of it is held precariously.

Lack of secure land ownership affected women’s participation in the project’s out-grower scheme, which encouraged small-holders to shift from subsistence farming to commercial palm oil production. In theory, this was an opportunity for economic development for women, but as most did not legally own land as individuals, they could not access loans and credit schemes established to facilitate participation. Most women therefore participated in the project as families, which gave men more decision-making power in terms of finance, what to plant and where, methods of payment from the factory once the oil palms had begun producing and opening bank accounts for payments (mostly in men’s names). This was despite the fact that women were expected to contribute most of the work involved in establishing the plantations on the family land. These issues also extended to compensation that families were awarded; most women were not involved in discussions around compensation or how any money received was spent.9

Women on the island are generally only able to access the lowest paid jobs on the plantations due patriarchal gender norms. Tasks such as harvesting and pruning are considered too hard for women, who usually just gather fallen fruit during harvest. This discrimination affects younger women in particular, since the lack of decent livelihood opportunities forces them to move to cities.10

It is clear that the palm oil project has caused more harm than good when it comes to women’s livelihoods in Kalangala. Despite this and the unresolved problems and conflicts that remain, the project is planning to expand to Buvuma, another island district where more havoc, violations of community rights and disruption of women’s livelihoods is unfortunately inevitable.

1 https://www.ifad.org/documents/38714182/39729786/Vegetable+Oil+Development+Project+(VODP).pdf

2 https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2015/mar/03/ugandan-farmers-take-on-palm-oil-giants-over-land-grab-claims

3 http://www.cao-ombudsman.org/cases/case_detail.aspx?id=254

4 https://www.ifad.org/documents/38714182/39729786/Vegetable+Oil+Development+Project+(VODP).pdf

5 https://theecologist.org/2015/feb/19/un-banks-and-oil-palm-giants-feast-stolen-land-ugandas-dispossessed

6 https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2015/mar/03/ugandan-farmers-take-on-palm-oil-giants-over-land-grab-claims

7 https://www.tropenbos.org/resources/publications/gender-based+impacts+of+commercial+oil+palm+plantations+in+kalangala

8 https://www.icrw.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Gender-Land-and-Asset-Survey-Uganda.pdf

9 Ibid.

10 https://www.tropenbos.org/resources/publications/gender-based+impacts+of+commercial+oil+palm+plantations+in+kalangala

West Papua: Depths of loss and heights of resistance

By Rachel Smolker, Biofuelwatch, USA, and Sophie Chao, University of Sydney, Australia

This is the statement of a Marind elder in the rural district of Merauke, in West Papua. Targeted by Singapore, South Korea and the Indonesian government, the lands of Indigenous Marind are being grabbed from them without consent and converted at an alarming rate from lush, biodiverse, sustaining tropical forests, into industrial palm oil plantations. The island of New Guinea, of which West Papua is the western half and under occupation by the Indonesian government, holds the third largest area of primary tropical forest after the Amazon and Congo Basin. And it is under serious threat from extractive industries. Having already ravaged much of Indonesia and Malaysia, the palm oil industry has turned its sights on Papua as the new agribusiness frontier. The Indonesian government has offered vast concessions – up to 90,000 hectares apiece – for logging and palm oil development.

This process began in the early years of Indonesian colonisation in the 1960s and has intensified drastically in recent years.1 Corruption in the West Papuan palm oil and timber sectors is the norm. Some concessions have been granted illegally2 and are held under a labyrynthine matrix of shell corporations, remarkably adept at evading any scrutiny.

A recently published, powerful expose3 conveys the sense of loss that the Marind people are experiencing as their forests have been converted to plantations, and their connection to traditions and cultural practices have been severed. As is always the case, the worst impacts fall upon women, who care for and feed their families. The expose describes a visit to a Marind family. A mother was holding what appeared to be a bundle of sticks that turned out to be a starving baby’s limbs. Unable to feed herself, the woman could not provide milk and was powerless to save her child who died that same evening. Without their forests, the Marind are slowly starving. Children suffer from malnutrition. There is no game. Fish are too contaminated by pesticides and palm oil mill effluents to eat. Instead people subsist, but never thrive on a diet of instant noodles and imported white rice, which is both nutritionally poor and culturally alien.

It is not just hunger and a lack of traditional foods that the palm oil industry has provoked among the Marind. The entire fabric of their beautiful rich and ancient culture has been unraveled. They can no longer teach their skills to their children, or take pride in their abilities to hunt, fish, and forage. They no longer practice their traditional rituals which were finely attuned to respecting and honoring the forest life and the living beings within it that sustained them. Sophie describes the Marind belief in common ancestry with the plants and animals of their forests – the practices of mutual support – clearing paths to water for wild pigs, scattering feed to attract cassowaries, pruning and tending useful plants, preventing disturbance to birds during the nesting season.

The expose describes how, “In the past, food scarcity was attributed to the wrongs and mistakes of Marind themselves, and particularly their failure to protect the forest environment. But now, the forest is being obliterated by powerful outsiders whose actions Marind have little power to control. This produces a seemingly inescapable double bind. Marind must sustain their customs and protect the forest to satisfy the ancestral spirits and sustain their forest food systems. Yet Marind are also vulnerable to the powers of corporations who destroy the very landscape from which these foods are derived. These two dimensions are irreconcilable. Together, they lead to a profound and ongoing erosion of Marind culture in the face of capitalistic forces, whose hunger for land and profit erodes the vulnerable beings and bodies dwelling upon and with it.”

What is happening to the Marind must resonate for all of humanity. The profound loss and disempowerment that these Indigenous communities are experiencing in the wake of logging and palm oil development is different, but the same, for people everywhere who are losing their connection to place, to nature, to the source of life and to cultures of meaning and worth.

Papua is referred to as the place “where rights come to die”. But we cannot allow that to happen! The loss, not only for Papuans, but for all of us, will be far too great. The exploitation of Papua has begun, but is nowhere near completed. There is still time for successful resistance to prevail. Papuans are resisting, overcoming tremendous odds, oppression and obstacles. Their spirit of opposition is beautifully portrayed in a recent digital art exhibit.4

In Merauke, Indigenous Marind continue to struggle to protect their customary lands and forests from the palm oil incursion. Women are part of this movement too, albeit in more everyday and small gestures of resistance. These include insisting on taking their children to the forest to get to know the plants and animals with whom they share kinship. It includes passing on to their children the many stories and songs that speak to the beauty and richness of the forest environment. It also includes celebrating the cultural significance of forest foods, and refusing to abandon this diet in favor of rice and instant noodles. These seemingly mundane acts matter in a world where the most basic of rights and needs are being violated in the name of agro-industrial development.

1 https://www.downtoearth-indonesia.org/story/twenty-two-years-top-down-resource-exploitation-papua

Eucalyptus monocultures: The green cancer plaguing rural women in Paraguay

By Fosco E. Gugliotta-Ruggeri Chaparro, Heñói, Paraguay

Afforestation and reforestation with harmful non-native species carried out ostensibly for economic and rural development has been a trend throughout Paraguay. These forestry practices—wrongly labelled environmental “achievements”—base their success on hectares covered by eucalyptus, a species that, forcibly and insistently introduced into the national biotope, is portrayed as common but is in fact foreign and invasive.

The main setting for afforestation with these varieties is rural areas distributed throughout the territory. Crops are grown for logging, “greening” cities, “improving” municipal land, and forest “recovery” promoted by some government body or arm. Meanwhile, our authorities boast about this nonsense and maintain that these are model methods.

For example, the second official report on presidential management states that 7,000 hectares of “native forests [were] recomposed with exotic eucalyptus,” concepts that are contradictory and cannot be used together in a logical statement, much less a system defined as natural and balanced.

This phenomenon leads to the deterioration of not only natural elements, but also the social system, exacerbating inequalities between groups that were already apparent before these types of enabling situations arose.

This is also the case with women’s relationships to the rural environment, expressed in their codependence, which is impacted by external factors that push them toward worsened connections and increased stress, testing their capacity for resilience and resistance, which is already limited by inequality.

In Paraguay, 38.5% of rural women lack incomes of their own; for female-headed rural households, the poverty rate is 55.3%, and extreme poverty stands at 35%. Meanwhile, two-fifths of rural women rely on or work in agriculture; 53.2% do so independently and 9.7% work in family units without receiving remuneration.1 Women suffer especially acutely the consequences of the unsustainable and large-scale exploitation that characterises extractivism, with eucalyptus monocultures being a current causal variable of the negative impact of the expansion of agribusiness.

In the community of San Isidro in the Department of Misiones, a communal field was planted with eucalyptus with the promise of a silvopastoral system that not only failed to produce benefits, but also stripped the area of the ecosystem services it offered, directly affecting its users. During a recent dialogue with local women, a local head-of-household named Ana2 explains: “the countryside was practically destroyed. They told us, wait until the trees grow to see benefits, and in the meantime, the site could not be used, and I had to pay for my cows to graze elsewhere. The trees grew, and now there is not even any pasture because of the shade. They never asked us, the just told us when the project was to start. I felt that, as always, it was supposedly a decision by politicians and men’s matters. What these male politicians did affected us working women and our families.”

Aspects of this tale are common denominators in the lived experiences of other women made victims by this situation. When the dialogue with Ana was organised, a group of women who gathered anonymously at the site offered statements such as, “We feel abandoned,” “we continue to struggle,” “we try cattle-raising, we try agriculture, we sometimes feel that we have no way out,” and “I don’t understand why someone has to decide what’s best for my family; who better than me to make that decision?”

Peasant and Indigenous women are deprived of the opportunity to support their families or enjoy economic freedom, forced to walk kilometres or pay for places to graze their cattle, deprived of communal spaces of production, excluded from processes of decision-making that directly influence their lives, and forced to compete against major agricultural players in a battle that is lost even before it has been fought.

There are many specific experiences of this, and we constantly see how they are barely addressed or taken very lightly, obscured behind ineffective “environmental achievements” and unrealistic “savior techniques” that expose mechanisms of rights violations.

A critical diagnosis of the national situation with regard to these metastasising practices is urgent. We must act immediately. We are already aware of the pre-pandemic situation, and we must now analyse the current circumstances to establish objectives and confront the dark post-pandemic scenarios that surely lie ahead if we fail to act.

At Heñói, we focus on and deepen our efforts to address pillars such as rural/urban sustainability; women’s relationship to the countryside; food sovereignty, food security and the right to food; and particularly generating social consciousness, which is essential if we are to patch the large holes that are sinking our boat.

1 Guereña, A. 2017. Kuña ha yvy: desigualdades de género en el acceso a la tierra del Paraguay – informe de investigación. ONU Mujeres / Oxfam Paraguay. 30p. https://www2.unwomen.org/-/media/field%20office%20americas/documentos/publicaciones/08/kuahayvyweb.pdf?la=es&vs=2633

2 Ana is a pseudonym; for personal reasons, the interviewee did not wish to reveal her real name.

The impacts of tree plantations and forced evictions on Indigenous women in Gorkha municipality, Nepal

By Shova Neupane and Bhola Bhattarai, NAFAN, and Rejan Rana Magar, local resident, Nepal

In 1985, the government of Nepal requisitioned over 1,000 hectares of forest land from Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPLCs) in eight villages in Gorkha municipality for a tourism mega-project involving the redevelopment of the Gorkha Palace.1

In the name of conservation, Indigenous Magar, Bhujel and other communities that had lived for generations on the hillside around the Palace were removed from their land, denied access to it and received minimal compensation for what had been taken from them.

After the requisition of the area around the Palace, the Government of Nepal developed a long-term conservation and development plan for the site in order to be able to welcome greater numbers of domestic and international tourists. As well as renovating historic buildings, the project’s major intervention was to introduce tree plantations on this so-called degraded land.

35 years since the requisition, much of the land has now been converted into dense pine, alder (uttis in Nepali) and wild cherry (painyu in Nepali) plantations, amongst other species. The plantations were established on designated Rani ban (Religious Forest) and newly afforested former agricultural lands, and the species were chosen without consultation with local communities.

NAFAN visited the villages surrounding the Gorkha Palace in August 2020 to find out how they have been impacted by the plantations. Focusing on the impacts on Indigenous women in particular, interviews were conducted with ten individuals, six of whom were Indigenous women.

For the communities, their exclusion from the land where the plantations were established and other human rights violations has been a major issue. Conservation policies implemented without consultation and based on restricting access have endured for decades, and have created much resentment between local people and the Palace administration. Their access to forest resources has been continuously denied and, as a result, Magar families and other Indigenous Peoples have been forced to leave the area.

Although the trees have now matured and some have begun to fall down because of wind, Palace authorities still refuse local people access to the plantations. This impacts local women disproportionately as it is traditionally their role to collect firewood, forest foods, fodder and other non-timber forest products, meaning that they must travel two or three hours on foot to forests that they are allowed access to. This significantly increases their workload.

Despite the restrictions, some people have continued to enter the area to collect the resources needed for their own survival, which has generated further conflicts. For example, local women described how the army and police arrest, beat and harass them if they go onto the Palace land (which includes plantations and forests). They stated that there have been a number of cases of sexual harassment by the police and army, and the women also revealed that there are no grievance redressal mechanisms if they are accused of committing a crime.

Another issue disproportionately impacting women as small-scale farmers is the fact that conflict between humans and wildlife is also increasing, due to the fact that the plantations provide habitat for certain animals. Women are finding it harder to rear goats and hens because of attacks by jackals and wild leopards, and deer also routinely destroy crops. This impacts on local food security as well as women’s livelihood opportunities.

In 2010, the villagers started organising to regain access to their forests and take over management of the plantations. They went to the District Forest Office (DFO) and demanded that the land be placed under community management, as is their right under the 1993 Forest Act. Local communities formed ten community forest user groups (CFUGs), but they were not legally recognised by the DFO. They also organised a series of dialogues with forest authorities and other stakeholders at the district level, and sent their claim to the Department of Forests (DoF), but they did not respond positively. Whilst the communities argued that the land should be designated as National Forest, and therefore governed by CFUGs, the authorities argued that the forest fell under the jurisdiction of the Gorkha Palace and it was not in their power to hand it over. This discussion is still ongoing at different levels.

After continuous advocacy and lobbying by local women and Indigenous Peoples aimed at the Mayor of Gorkha municipality and the DFO, 32 hectares of forest land in Phinam village was finally handed over to the Bajra-Bhirav Community Forest User Group in 2018. The CFUG now has access to non-timber forest products, firewood, timber, wild fruits and recreational activities from their corner of the forest. They are also building a viewing tower and developing a recreational center to encourage visitors to their community forest area, as an additional and sustainable livelihood activity for local families.

Placing the land under community management benefits Indigenous women as CFUGs are seen as a vehicle for women’s empowerment and social transformation in Nepal. At least 50% of CFUG committee members must be women, and they aim to provide equal opportunities in decision-making and benefit-sharing. Community control of the plantations would also allow equitable use of the resources that exist there, and the potential for the land to be converted back to forest and agricultural land.

1 Nepal’s Gorkha Palace is a historic landmark built in the 16th century and sits on a hill 141 kilometres west of Kathmandu. It is famous for being the birthplace of King Prithvi Narayan Shah who started the movement for the unification of Nepal.

Forest protection and women’s rights must go hand-in-hand in Rwanda

By Aphrodice Nshimiyimana, Global Initiative for Environment and Reconciliation, Rwanda

An event aimed at protecting indigenous trees in Rwanda. Global Initiative for Environment and Reconciliation (GER)

Despite the progress made by the government of Rwanda in environmental management and gender equality, including a 30% quota for women in all decision-making roles and 64% of parliamentarians being women in 2020, women still face gender inequalities.

Rwanda’s high population density and growing population means that land is used very intensively, which promotes commercial and monoculture tree plantations while natural forests are still under pressure. It is claimed that “forests” cover 29.8% of the country, but 60% of this tree cover consists of plantations, compared to 40% natural forests.1 This intensive forestry model impacts women in particular because they are primarily responsible for two major livelihood activities requiring land and forests: farming and gathering firewood.

The key drivers of this shift from natural forests to plantations are high population growth, with 83.5% of people still living in rural areas and with limited access to land to sustain their livelihoods, and increasing pressure on natural forests from industrial agriculture, urbanisation and exploitation of forest resources. The failure of efforts aiming to promote sustainable forest management and the full engagement of local communities2 and the enduring impacts of the 1994 genocide against the Tutsis mean that there is a general lack of awareness amongst the population of the distinction between forests and monoculture tree plantations. A disconnection between people’s relationship with nature and a generational community knowledge gap3 is leading to the extinction of some species of indigenous trees and, on top of this, climate change is also influencing the loss of natural forest cover.

Almost two-thirds of Rwanda’s forests have been lost since the 1960s, and demand for biomass energy continues to be a major driver of deforestation.4 According to a report by the Ministry of Land and Forests, “forests” provide 98.5% of Rwanda’s primary energy needs, mainly for domestic cooking, where more than 95% of the rural population relies on wood for fuel.5 It has often been suggested, including by the government,6 that demand for fuel wood should be met by further expanding and intensifying wood production in monoculture tree plantations. However, no figures currently exist indicating whether fuel wood is sourced primarily from plantations or forests. Since plantations are used commercially for timber and other purposes, they are highly protected, and women are not able to access them to gather fuel wood. Natural forests, on the other hand, are easily accessed by rural communities.

There is also limited recognition of women’s role in the forestry sector, such as their involvement in forest protection and conservation, and the benefits of forest resources are not equally shared. Hence, little attention has been given to redesigning forestry-related practices to meet women’s unique needs, particularly in light of their household responsibilities, or to empower women to participate in decision-making and take opportunities at management level.7

Further still, women are most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change and forest destruction due to their traditional roles of gathering fuel and cooking for their household using wood or charcoal.8

These domestic activities are considered less valuable and force women to stay at home, which is a significant trigger of gender inequality.9 This workload reduces educational opportunities for women and girls, reinforcing inequality. Another significant factor is that the fumes and smoke produced by wood combustion affect women’s respiratory system and eyes, causing poor health and an additional gender-differentiated burden.

Several projects have sought to introduce changes, but rather than promoting genuine local sustainable energy alternatives, they focus on innovations in wood fuel consumption and reducing pollution from wood combustion. They involve cookstoves that aim to be both wood efficient and cost effective, limiting the quantity of wood and charcoal burned. However, the communities using them are still reliant on wood for their domestic energy needs, which means that forests are still under pressure. There is also little evidence that wood use is actually reduced, or that women’s health is improved through their use.

The Global Initiative for Environment and Reconciliation, as an organisation working with communities to support peacebuilding and improved environmental protection, advocates for parallel efforts to protect forests and work towards gender equality in Rwanda. Women’s participation and voices in community forest management must be increased to improve forest governance and sustainability, and there should be a joint focus on reducing deforestation of natural forests, including by distinguishing them clearly from tree plantations and raising awareness of the drivers of deforestation and how they affect women in particular.

At the same time, there must be a fight for gender equality in the home. Women require genuinely sustainable cooking alternatives that do not harm their health, and this should go hand-in-hand with a campaign calling upon men, especially in rural areas, to do their fair share of domestic activities such as cooking. This will undoubtedly lead to more attention for genuinely sustainable energy alternatives that go beyond using wood for fuel.

These important interventions will not only promote women’s rights and reduce women’s workload, but will also boost natural forest cover, protect biodiversity and help in climate change mitigation and adaptation.

1 http://www.rwfa.rw/index.php?id=35

2 https://www.climateinvestmentfunds.org/sites/cif_enc/files/fip_final_rwanda.pdf

3 GER, 2017. Documentation of traditional knowledge associated with environment conservation in Rwanda.

4 https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2018/12/19/beyond-charcoal-how-one-company-helps-rwandan-families-save-their-health-and-the-environment-one-cookstove-at-a-time

5 https://environment.gov.rw/fileadmin/NDC/FIP%20%281%29.pdf

6 https://environment.gov.rw/fileadmin/Media_Center/Documents/Rwanda_Supply_Master_Plan_for_Fuelwood_and_Charcoal.pdf

7 https://environment.gov.rw/fileadmin/NDC/FIP%20%281%29.pdf

8 http://www.fao.org/sustainable-forest-management/toolbox/modules/wood-energy/basic-knowledge/en/?type=111

9 http://www.rwfa.rw/fileadmin/user_upload/Rwanda_National_Forestry_Policy_2018.pdf

Confronting the impacts of the plantation forestry model in Chile

By Constanza Ramos, Camila Romero and Antonio Saldías, Colectivo VientoSur, Chile

From different areas of Abya Yala (“the flowering land” or the Americas), people are rising up to reclaim our history. The memory of looting and pillaging, which is so present as a reality, mobilises us to recover the future, which beats ever stronger in our bodies and territories.

This article has two aims: to make visible two territories that are resisting the extractivist forestry model and some of their organisational strategies, and to address in a general sense the gender-differentiated impacts of the forestry model on women.

Chile’s economy is mainly based around the exportation of natural common goods, and the forestry sector is the second largest contributor to national GDP after mining. Along these lines, extractivist policies have been systematically implemented and deepened since the dictatorship (1973-1990) through to present day. In this model of accumulation through dispossession, mega-companies absorb capital gains from surpluses derived from the appropriation and privatisation of common goods, whilst enjoying protection from the state.

Chile’s forestry market is controlled by two large groups that account for around 60% of investment in the sector: The Angelini Group has the biggest presence, with Forestal Arauco and Celulosa Arauco, whilst the Matte Group controls Forestal Minico and Celulosa CMPC.

This scenario is made possible through institutional violence carried out by the Chilean State and the criminalisation of social struggles, exercised primarily against Wallmapu1 communities. Where there was once recognition of the boundaries of the ancestral Mapuche land (Treaty of Tapihue of 1825) and their rights over the Fütawillimapu territory,2 the state now responds to the historic demands of the Mapuche people with the militarisation of their territory and detention of leaders and defenders, including women, children and the elderly.

In Chile’s Biobío Region, the Gulf of Arauco has been a “sacrifice zone” since the beginning of the 20th century with coal mining, the first thermal power plants, mega seaports and large-scale tree monocultures. Currently, Celulosa Arauco’s Horcones Complex is being modernised and expanded into a facility that will be the largest of its kind in Latin America and is projected to produce 2.1 million tonnes of pulp per year.

Meanwhile, the Valdivian Forest in the Los Ríos Region has seen the destruction of native forests for logging, agriculture and livestock production. Here, five million hectares have been reforested since 2016 with monocultures of non-native species of eucalyptus and pine.3 Celulosa Arauco’s Valdivia Plant in the town of San José de la Mariquina aims in 2020 to become the country’s first producer and exporter of textile pulp.4

After a little more than three decades of plantation forestry in Chile, the socio-environmental impacts caused in the territories have become apparent. With regard to the environment, these include the loss of water systems and native forests,5 the deterioration of soil quality6 and increased forest fires.7 From a social perspective, and with gender-differentiated impacts, there is increased unemployment and migration,8 the deterioration of local cultural patterns, food sovereignty under threat and a decrease in intergenerational transmission of local knowledge. On top of this, there is community fragmentation and loss of identity, and inhabitants of these territories experience environmental racism.

The impacts of forestry fall particularly on women, who are traditionally the reproducers of life and culture. For example, water scarcity caused by tree plantations affects women in the communities primarily because they are in charge of childrearing and care, the transmission of culture, subsistence agriculture and cattle raising and handicrafts, among other roles—all activities for which water is essential.

Women have played an important role in territorial struggles against tree plantations, ensuring that culture and spirituality are upheld, guaranteeing the inclusion of new generations and building their knowledge and capacities. An example is the promotion of Küme Mongen,9 the recovery of Mapuche health and agroecological production implemented by the Asociación Trem Trem Mapu.10

In Mapuche communities, women have a strong influence on the management of cultural codes that support territorial demands. Their active involvement in care, domestic and administrative tasks ensures unity in the communities, contributing to organic and internal organisational cohesion. External political power is often monopolised by men. Women demonstrate that upholding customs serves a dual purpose: on the one hand, it empowers, with regard to the transmission of culture, language and food to young people, which becomes political; and on the other, through the defense of rights and territories, one acquires consciousness that domestic violence and abuse is also political and not private, and tools can be generated to confront these problems.

In short, Chile’s extractivist model of the production of raw materials, that is based on pillaging, has strengthened the neoliberal economic system promoted by the state. In this context, plantation forestry is of special relevance due to the territorial impacts it causes and the environmental racism and sexism it imposes on Indigenous and peasant communities, and particularly women.

1 Name given to the territory traditionally inhabited by the Mapuche Indigenous People.

2 The Mapuche’s “great land to the south”.

3 CONAF (2016), Plantaciones Forestales: Supericie Anual Forestada y Reforestada. https://www.conaf.cl/nuestros-bosques/bosques-en-chile/estadisticas-forestales/

4 https://www.mundomaritimo.cl/noticias/arauco-desde-2020-producira-por-primera-vez-pulpa-textil-en-chile-para-exportar-al-mercado-asiatico

5 Torres-Salinas, Robinson et al. (2016), “Desarrollo Forestal, escasez hídrica y la protesta ambiental Mapuche por la justicia ambiental en Chile,” Ambiente & Sociedade, XIX(1),121-145. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=317/31745308005

6 Mauro E González et al. (2011), BOSQUE 32(3): 215-219, https://scielo.conicyt.cl/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0717-92002011000300002&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en

7 Nicolás Sepúlveda (2017) La grave crisis de agua en los pueblos arrasados por el fuego, Reportaje de El Mostrador https://www.ciperchile.cl/2017/01/31/la-grave-crisis-de-agua-en-los-pueblos-arrasados-por-el-fuego

8 Andersson, K., Lawrence et al. (2016), “More trees, more poverty? The socioeconomic effects of tree plantations in Chile, 2001-2011, ” Environmental Management 57(1), 123-136)

9 An Indigenous term for what is known in Spanish as buen vivir or “living well.”

10 See the Women2030 Global Shadow Report: https://www.wecf.org/global-shadow-report-gender-equality-on-the-ground-feminist-findings-and-recommendations-for-achieving-agenda-2030/

Resistance, autonomy and reclaiming forests: How Baiga women transformed a marginalised Indigenous community in India

by Kanta Marathe, All India Forum of Forest Movements, and Devjit Nandi, Navrachna, India

Historically, the Baiga Indigenous tribal community residing in the Central Indian forest tracts has always resisted the plantation drive by the state Forest Departments. To them, planting monoculture trees means losing their land, access to forests and traditional practice of swidden agriculture. They are the most marginalised Indigenous forest communities, officially designated as a particularly vulnerable tribal group.

A little over 21,000 Baigas reside in the forests of Bilaspur district in the Central Indian State of Chhattisgarh. They are completely dependent on forests for their survival and livelihoods. They have a symbiotic relationship with nature in which traditional knowledge and wisdom on sustainable conservation and biodiversity protection is passed on through generations. It is generally Baiga women who access the forests for non-timber forest products and practice no-till agriculture, mainly planting fruit trees and coarse cereals. The Baigas are also traditionally bamboo artisans, and their villages grow bamboo to sustain their livelihoods.

During the last two decades, with the enactment of the Forest Rights Act and able support of Navrachna,1 the Baigas in the sub-divisions of Kota and Pendra have asserted their political sovereignty through the formation of autonomous Gram Sabhas (Village Councils) and Forest Rights Committees to challenge the dominance of the Forest Department. Women in particular have led this movement to govern their own forests and resources. They have resisted the large-scale expansion of eucalyptus and jatropha plantations on their land and have even uprooted jatropha trees planted without their consent for biofuel cultivation.

The Indian Government’s National Biodiesel Mission identified non-native jatropha as a feedstock for proposed biodiesel production and a campaign was launched in Chhattisgarh to promote jatropha cultivation with the intent of making it the biofuel hub of India. Thus, jatropha plantations were forcefully introduced on disputed forest lands by the Forest Department, evicting Indigenous communities from their ancestral territories. The Forest Department has also tried to introduce eucalyptus, another fast-growing tree that consumes a large amount of groundwater. Both types of plantations take land away from forest-dwelling communities and keep the land locked into that type of production for at least seven to ten years. During this time, rightsholders cannot use the land for their own livelihoods and their agricultural practices also suffer due to impacts on water availability.

There is a strong history of Baiga resistance to plantations. In 2007, 26 women from Phulwariapara village were arrested for uprooting jatropha trees. In November 2019, the Forest Department falsely punished two women and four men from the same village for stopping a truckload of illegal timber and resisting monoculture plantations and detained them in Bilaspur central jail for 17 days. Baiga women in Phulwariapara used to be afraid of the Forest Department and would wait until dusk to return to their homes. Now, however, led by Sushila Baiga, a Baiga woman who is president of the local Forest Rights Committee, they have taken the initiative to build local governance institutions, filed their legitimate claims and rights over community resources and developed village-level plans for the conservation, restoration and regeneration of forests on five hectares of land. They have grown bamboo and fruit trees, developed seed banks and prepared a biodiversity register.

In Chuhiya village, women with the help of Navrachna organised a resource mapping of the Saliha Dongari community forest territory, and now about 18 hectares of land is being regenerated. The villagers monitor the regeneration and reforestation work regularly and all 65 families in the village have a shared responsibility to protect biodiversity and halt forest loss. The Forest Rights Committee has constructed water harvesting structures and plans to cultivate medicinal plants such as harra (Terminalia chebula), behra (Terminalia bellirica) and aonla (Emblica officinalis) in its nursery. The committee has further banned the felling of standing trees, and only ripe fruits may be collected.

Chuhiya resident Dukaini Bai explains, “We now govern our own forests and resources. We not only oppose and resist monoculture plantations but [also] are equally committed to restoring our forests and lost biodiversity.”

Baiga women’s participation in biodiversity conservation and village development provides them with livelihood opportunities that break the chains of poverty and malnutrition. The forests of both villages are flush with mahua (Madhuca longifolia), char (Buchanania lanzan), neem (Azadirachta indica) and mango trees. Cattle grazing has been regulated and the women now fearlessly enter their forests to collect leaves, fruits, roots, tubers, mushrooms and gums.

Events in Chuhiya and Phulwaripara have triggered a domino effect on the Baiga in other forest areas of the district. The movement to resist monoculture plantations, illegal logging and the destruction of forest biodiversity has now matured into a movement for self-governance, reclaiming forests, traditional practices and community-governed conservation and biodiversity protection. It is a movement led by brave Baiga women.

1 Navrachna is a Global Forest Coalition member group and constituent of the All India Forum of Forest Movements.

Industrial forestry versus wetlands in an Argentina in flames: Environmental defenders to the rescue of diverse and dissident nature

By Emilio Spataro, Amigos de la Tierra, Argentina

Argentina is in flames. The combination of climatic factors (a dry year and exhausted lakes and rivers) and a quarantine that has lasted over 150 days has found a population confined to their homes as the extractivist models of development continue to function at full speed, with thousands of wildfires devouring forests and wetlands.

The smoke covering cities and Dantesque images of wetlands being consumed by immense flames have mobilised the population, and hence civil society is demanding that a law be passed to protect Argentina’s wetlands.

This demand is not a new one; the initiative arose in 2012 out of citizens’ assemblies and environmental and peasants’ organisations, and then for years confronted the advance of extractivism in different wetland regions. Among these are the Iberá Wetlands in Corrientes Province, which have been designated a Ramsar site. This province, which borders Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay, is home to 65% of Argentina’s forest plantations, a total of 516,771 hectares that have been planted over the last 20 years,1 replacing wetlands and savannahs of palm groves—and to a lesser extent, native forests—due to a neoliberal law that has benefitted the sector through tax exemptions and subsidies (Law No. 25080).

However, promises of development are still ephemeral. Even before the COVID-19 crisis, more than 45% of the population was living below the poverty line,2 and in the forestry sector, 65% of workers face informal and precarious working conditions (even cases of slave labour).3

In this context, peasant women and those from small towns suffer the most and face the consequences of environmental dispossession and negative changes in the lives of their communities due to the forestry model. Today, roles in health care, nutrition and wellbeing are nearly entirely in the hands of women.

Many peasant women in the rural areas of the Municipio de San Miguel state that the destruction of roads by forestry trucks impedes access by ambulances and drives up the cost of transportation. The companies do not help repair them, and the municipality does not have money to do it, partly because, according to Law No. 25080, companies are exempt from paying local taxes. Meanwhile, soil preparation for tree crops involves the use of herbicides and insecticides for ants. In the Municipio de Puerto Piray (Misiones Province), peasant women from the organisation PIP-UTT have repeatedly spoken out against the contamination of water due to the use of agrochemicals in the forest plantations. It is also worth noting that women’s workload is increased due to the health problems suffered by male forestry workers, because spouses need extra care and cease to earn incomes. These are situations with serious family consequences, and they are particularly visible in the Municipio de Santa Rosa (Corrientes), which has a large number of sawmills with dire working conditions.

Therefore, it is no accident that they are the ones who have initiated and sustained actions of protest and struggle against forest plantations. Such is the case in the small town of Chavarría (with 3,000 inhabitants) in the heart of Corrientes Province. The area of pastures, savannahs and wetlands has been transformed into forest monocultures by the EVASA company, which is owned by the Harvard Management Company (the company in charge of Harvard University’s endowment).4

In 2012, a group of women from Chavarría cut off the road indefinitely, blocking the passage of EVASA’s forestry trucks until a solution could be found to their incessant passage through the town. In statements to the media, the women said they were “tired of their children having respiratory problems because of the dust stirred up by the trucks on dirt roads in the small town, and that they also interrupt their rest during the siesta.”5 Because of their determination and direct action, the company had to build an alternate route for its trucks.

This is just one example. The basic problem is one of occupation of space. In the towns of Santa Rosa and Tatacua, peasant women are facing the challenge of lack of land on which to live and grow crops. The forest plantations gobble up everything (next to Corrientes is Misiones Province, which has the largest proportion of land in foreign hands). Because of this, a group of women has sustained the peaceful occupation and defence of peasant lands, regulating the size of the areas for production and housing themselves. In this town, the dispute over space also involves makeshift sawmills, which harm human health by burning sawdust, the environment by filling wetlands with the residue, and workers due to the high rate of amputations and serious injuries to extremities because of poor working conditions.6

A brave Guaraní woman resident of the Iberá Wetlands spoke in Congress on behalf of the thousands of women who defend the country’s wetlands, saying, “from this debate one thing must be made clear: we have already chosen the type of life we want, we have decided that it is agroecology and food sovereignty, the pillars of our production. We are the children of the earth, [we are] part of her, and nothing will change that. Today, it is you the legislators who must decide to protect our laws, our way of life, and not only ours, but that of everybody, of all Argentines.”7

1 Divulgación de cifras oficiales sobre plantaciones forestales de la Provincia de Corrientes; https://www.ellitoral.com.ar/corrientes/2019-5-2-4-2-0-corrientes-cuenta-con-516-771-hectareas-de-bosques-cultivados

2 Índice de pobreza de la Provincia de Corrientes previo a la crisis del Covid (2019); https://www.nortecorrientes.com/146105-corrientes-encabeza-el-ranking-de-la-pobreza-del-pais-con-casi-el-50

3 Bardomás S.M. Blanco M. (2018). Condiciones laborales, riesgo y salud de los trabajadores forestales de Misiones, Corrientes y Entre Ríos (Argentina), 2010-2014. Salud Colectiva. Universidad Nacional de Lanús. https://scielosp.org/pdf/scol/2018.v14n4/695-711/es

4 More information about the forestry activities of the Harvard investment fund in Corrientes Province can be found at: https://www.lavaca.org/notas/harvard-reclamo-contra-las-inversiones-de-la-universidad-en-monocultivos-en-el-ibera/

5 Silvia Yacuzzi, neighbour of Chavarría and founder of the socio-environmental organization Guardianes del Iberá.

6 Interviews and statements by Alejandra Aquino, peasant representative of FeCaGua (Federación Campesina Guaraní de Corrientes) at the Federation’s 3rd annual plenary. https://www.facebook.com/groups/qgis3/permalink/2943415779267733/?app=fbl

8 Mirian Sotelo of FeCaGua (Federación Campesina Guaraní) and CPI Representative of the Pueblo Guaraní de Corrientes, Comunidad Jahavere. Mirian Sotelo. (2020). Ley de Humedales 2020. Aportes legislativos 2º Reunión informativa- 13 de agosto del 2020. Comisión de Recursos Naturales y Conservación del Ambiente Humano. Cámara de Diputados de la Nación.

Conclusion

By Jeanette Sequeira, Global Forest Coalition, Netherlands

Commonalities between the diverse examples of how tree plantations impact women

From replacing important forests and wetlands and dispossessing community lands in the name of conservation or resource extraction, to undermining water availability and food security, commercial monocultures continue to leave a path of destruction with a myriad of impacts on women and their communities.

These impacts are felt across and within communities in different ways, depending on the needs, rights, roles and priorities of different members of the community. This report highlights how Indigenous and peasant women of colour are especially affected due to pre-existing structural and institutional discrimination and violence—including environmental racism. Female-headed households and women without secure land tenure or with little influence over land and forest governance and other decisions that directly influence their lives are also particularly at risk.

In several cases described throughout this report, industrial plantations have displaced communities, capitalised on already insecure land tenure arrangements, reinforced bioenergy use with harmful impacts on women’s health and induced further deforestation, biodiversity loss and local food insecurity. In turn, these impacts exacerbate existing inequalities, disrupt social structures in communities and deepen gender inequality, structural and environmental violence, and the violation of community and women’s rights. For instance, the violence, humiliation, harassment and exploitation of women described in this report are all symptoms of an exploitative industrial model followed by plantation companies that is rooted in patriarchy.

The impacts of tree plantations on women’s abilities to carry out their multifaceted roles in communities are visible throughout this report. However, a common thread is how plantations impede on women’s prevalent unpaid care and domestic work in sustaining and caring for households and communities. Work burdens related to producing and collecting food for household consumption, non-timber forest products, water, health care and wellbeing are intensified when local, biodiverse forests are privatised and replaced with monoculture tree plantations. In Rwanda, where 95% of the population relies on wood for fuel, a large part of women’s work involves collecting firewood. Not only does this workload hinder women from accessing educational opportunities, but the fumes and smoke from burning wood in the home has significant negative impacts on women’s respiratory systems and eyes.

This report tells stories of how living in, amongst and around plantations compounds the already heavy burden of reproductive work (often unpaid domestic, care and agricultural work) that women carry. This is worse for female-headed households where, in the case of Paraguay, 55% of such households live in poverty and 35% in extreme poverty. In Ghorka municipality in Nepal, Indigenous women rely on local forests for gathering firewood and non-timber forest products for subsistence. When the authorities declared their forest territory a conservation zone, established monoculture tree plantations— without free, prior and informed consent—and restricted access to it, they had to either travel further to find these resources or defy restrictions by entering the plantations at high personal risk. The experience of quilombola women in Brazil tells a similar story of how eucalyptus plantations for pulp production disrupted their ability to meet their nutritional, medicinal and cultural needs from local forests.

Whilst we must acknowledge the vital roles of women in transmitting cultural knowledge to younger generations and in sustaining life in communities, it should also be recognised how this can serve to reproduce patriarchal gender roles and institutional policies that confine women to domestic tasks and invisibilise women’s work. Where plantations impede or compound the work that women do, this becomes a self-reinforcing cycle that ensures gender-equality remains a distant prospect.

Increased sexual harassment and violence against women in communities dealing with commercial plantations is a major issue flagged throughout this report. In the case of Nepal, Indigenous women interviewed recounted incidents of having to endure arrests, physical assault and sexual harassment by army and police when trying to enter plantations to meet their subsistence needs. In Chile, the incidence of domestic violence and abuse in communities faced with rampant deforestation and commercial plantations is being understood as not only related to the private sphere but also political, connecting the structural violence and discrimination led by the state and forestry companies with community fragmentation and loss of cultural identity. There are several other studies globally that document the violence faced by women and their communities living in, amongst and around commercial tree plantations.1

In many cases, women have little influence over land tenure and governance issues, and this is exacerbated when plantations displace and dispossess communities, leaving them without land to subsist on. This issue is focused on in Kalangala, Uganda, where palm oil for vegetable oil production drove women off farmland since they had no ownership rights. Even where there was customary land tenure, traditional gender roles meant that women still needed permission to access land for their livelihood practices.

The undermining of local food security and community food sovereignty is also highlighted across the different accounts. For the Marind people in West Papua, food insecurity and hunger is fueled by palm oil plantations that have compromised the availability of traditional forest foods, and in India, eucalyptus and jatropha plantations have depleted water sources, in turn hindering the agricultural practices of Baiga women. In Nepal, small-scale women farmers have struggled to raise livestock for local consumption due to wildlife predators that have flourished in plantations that communities are excluded from.

Actions needed to protect women’s rights, community rights and forests

We need concerted action and strategies at multiple levels to combat the negative impacts of plantations on women and their communities, from the structural, institutional and fiscal/economic to the local levels.

Self-organisation and autonomy of community and women’s rights groups

The strengthening of autonomy of community groups and women’s rights groups to organise, strategise, gather evidence, resist and advocate for their own demands and forest conservation policies is central. In the case of women from Chavarria in Argentina, their direct action led to forestry companies building an alternate transport route that no longer ran through their small towns, something that was causing respiratory problems in their community. In Nepal, village members organised themselves into a Community Forest User Group and successfully advocated to local authorities to hand over hectares of forest land to their group, once again granting them access to forests for recreational activities, firewood and non-timber forest products.

Women’s leadership

Several accounts show the resilience and strength of women who are at the forefront of resistance movements against commercial plantation projects and leading local institutions that are fighting for forests and community rights. However, more generally, there is still work to do to ensure that women are systematically engaged in governance. Greater recognition and strengthening of the capacities of women leaders from communities to engage in leadership, decision-making and forest governance at community and other levels is a priority. While this requires a process of dialogue around concepts of gender and how inequalities are created within communities and institutions, it is important that opportunities are also afforded to women leaders to strengthen their capacities to claim political space to advocate for their rights and those of their communities against the impacts of plantations.

Strengthening governance institutions against corporate capture

The establishment of commercial plantation projects in contexts with weak governance often takes advantage of and worsens the insecure land tenure arrangements of Indigenous Peoples and local communities. The private investments of economically powerful actors such as big agribusiness and plantation companies should not steer governance of land and forests as they currently do. Despite the benefits of community tenure, rights and governance for forest conservation and sustainable livelihoods, these receive far less support than the false solution of commercial monocultures and the profitability they promise. Scrutinising corporate capture of forest policies and governance is important, as is strengthening community governance institutions and community rights over forest resources. In the case of the Baiga Indigenous tribal communities in Chhattisgarh, their creation of autonomous Forest Rights Committees and Village Councils shows how communities with women at the forefront create strong, local forest governance institutions that can put up resistance to imposed, detrimental state policies and industry projects.

Eliminating policies and financial incentives that promote plantations and supporting alternatives

Strong state sponsorship in the form of tax exemptions, subsidies, incentives and other (fiscal) policy support for a forestry model that promotes commercial plantations—as is described in Chile, Brazil, India, Paraguay and Uganda—need to be phased out or redirected. Instead, the examples in this report call for supporting community-based approaches to forest conservation and promoting sustainable livelihoods and food production through, for example, agroforestry and agroecology programmes. Through Küme Mongen, the Mapuche concept of well-being or buen vivir in Chile, there is renewed focus on Mapuche health and production of agroecological products as a clear alternative to the extractivist and colonialist plantation model. In Rwanda, where 60% of tree cover is made up of plantations, communities heavily depend on firewood and charcoal for their domestic energy needs. While the government supports the expansion of monoculture tree plantations and more efficient cooking methods to meet these needs, a far better option would be ending dependence on wood through genuinely local and sustainable energy alternatives that do not harm women’s health.

Legal support and awareness-raising

Civil society organisations supporting communities to take legal action or mediation with plantation companies is another approach to defend lands and seek compensation, as cited in the case of Uganda. In other cases, like in Rwanda, the importance of awareness campaigns on the impacts of monoculture plantations and drivers of deforestation as well as environmental education programmes can also play a role. In the latter, barriers to women’s access to education and training must be addressed, including sharing of domestic and other work responsibilities to ensure time availability as well as mobility restrictions amongst others.

Acknowledging and redistributing women’s unpaid care and domestic work burden

Since commercial plantations exacerbate women’s existing work burdens, it is imperative that policies and programmes to address plantations and promote alternatives recognise women’s unpaid care and domestic work and how it can be redistributed or supported—rather than consider it as less valuable. Redistribution is touched upon in the case of Rwanda, where a campaign to encourage men to share domestic activities such as cooking more equally is promoted. If men were to take a more active role in sourcing firewood and cooking, and were therefore more exposed to the impacts of this work, dependence on firewood would probably have ended long ago and been replaced by safer alternatives. The active participation of women and women’s organisations in planning, implementation and decision-making is a crucial way of acknowledging and integrating these needs and priorities that are specific to women and other groups that traditionally lack access to decision-making spaces.

Land tenure, governance and Free Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC)

Advocating for policies that enable communities to defend their territories against plantations industries and inclusively govern their forests is key. With greater land tenure and governance rights, governments and other actors must respect the FPIC of communities so that they are able to determine their own livelihoods and models of food production, whether through agroecology or organic family farming, while conserving their forests. This is particularly important for women, given their central role in food production and community biodiversity conservation and the substantial inequalities they face in terms of land rights.

Further analysis of the gender-differentiated impacts of monoculture tree plantations

More critical feminist and intersectional analyses are needed on how plantations are affecting communities and their livelihoods, including the gender-differentiated impacts and impacts on other excluded community groups whose voices are not often heard. Feminist analysis examines gendered power relations, intersectionality, structural barriers, gender-disaggregated data and documentation of stories and experiences of women and women’s rights groups, youth, elderly people and other excluded groups. The examples highlighted in this report show that there is huge potential for such work, drawing on the experiences and expertise of women, Indigenous Peoples, local communities and civil society groups.

1 See for example: Breaking the Silence, https://wrm.org.uy/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Breaking-the-Silence_8March2019.pdf; Turning Prairies into Desserts into Green Brazil, Friends of the Earth/World Rainforest Movement. http://www.globalbioenergy.org/uploads/media/0903_FriendsoftheEarth_-_Women_raise_their_voices_against_tree_plantations.pdf

Towards a focus on the sustainability of life

By Johanna Molina, Colectivo VientoSur and GFC board member for Latin America and the Caribbean, Chile

Among the origins of COVID-19 are deforestation, biodiversity loss and the growing invasion of forest and animal habitats, which are of course risk factors for the emergence of new coronavirus pandemics in future.1