Download the summary report here

INTRODUCTION

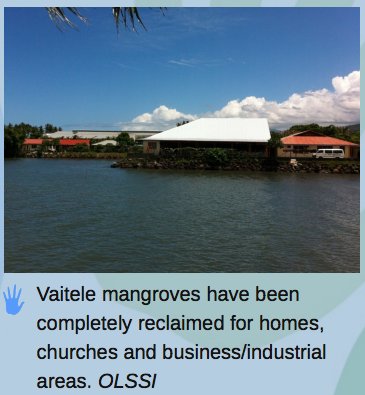

Ole Si’osi’omaga Society Incorporated (OLSSI) in Samoa conducted community consultations and mangrove surveys in the villages of Toamua, Saina and Vaiusu as the first part of the Community Conservation Resilience Initiative (CCRI). Samoan villages have sovereign governance directed by cultural protocols, with the land and sea controlled by a customary tenure system.[1] This has created problems for mangrove management because the government law states that all land under the highwater mark is government land.[2]

Many households in these villages still depend on mangrove ecosystem services like fisheries for food, security and income.[3] The mangroves are also home to a range of indigenous bird species.[4] However, the residents claim that ecosystem services have declined dramatically as a huge part of the mangroves have been destroyed due to urbanisation, industrial activities, population expansion, climate change and overharvesting.[5] Regrettably, legislation and protocols have been unable to prevent this ongoing disaster. Nonetheless, the government and communities have now joined forces to strengthen mangrove conservation and climate change resilience.[6]

COMMUNITY CONSERVATION RESILIENCE IN SAMOA

Through consultations and surveys, community members identified a range of threats to mangrove habitat and resources. Two major internal threats are wastewater and land reclamation.

Wastewater is discharged directly into the mangroves and lagoons promoting algal bloom, which can smother and kill young trees and seedlings. Additionally, land reclamation enhances siltation in the water, which smothers pneumatophores, limits nutrient supplies, and kills mango trees. This in turn results not only in a reduction in the number of fish, but also threatens the extinction of indigenous birds.[7] Local fisherfolk also cause some damage to young mangrove trees with their canoe hulls when they cross the foreshore at night, and pigs inhibit the growth of the young trees as they forage for food by digging in the mangrove areas.

The mangrove plantations are also prone to external threats including high tides and strong waves that break and uproot young trees. Climate change and rising sea levels have exacerbated these threats. In addition, the nearby Fulu’asou River has destroyed previous plantations when flooded and this is still a potential threat today. Solid waste, in particular plastic bags, can easily smother the young mangroves. Chemical pollution from waste dumps and sand dredging operations are also potential threats that need to be addressed.[8]

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The three communities are all committed to the Community Conservation Resilience Initiative (CCRI) and Vaiusu has already taken the next step to implement its commitment. The Vaiusu women’s committee has developed a two-acre mangrove plantation in an adjacent mudflat as part of its rehabilitation/conservation long-term plan. They recognise the need to reverse the conditions causing mangroves to decline. Mangroves are necessary not only for livelihood security, but for the health and resilience of the intricate network of interconnected ecosystems including lagoons, mudflats, seagrass beds and coral reefs.

Further, the communities have developed village bylaws focused on protecting the integrity of the habitat. These include a ban on cutting mangroves, unsustainable fishing practices and dumping rubbish in the mangroves. They have also begun a dialogue with the government and OLSSI to develop a mechanism to realise this focus.[9] As a result, they have collectively developed the Fishing guidelines[10] and Mangrove Biodiversity Audit.[11]

The communities have also asked the government to help improve sewage and waste management facilities to minimise leachates and to enforce legislation and national policies to limit mangrove conversion and to control sand mining.

Besides the government, support from donor agencies and other NGOs plays an important role in enhancing the resilience of communities. They can assist by providing funding and technical expertise. Though the communities are becoming aware of the vulnerable impacts of climate change they need capacity building, as it is an ongoing process. The community is committed but needs support to enhance their skills and revive traditional knowledge related to mangrove management. In particular women’s knowledge and participation in the decision making process needs to be encouraged in the conservation and resilience initiative. Furthermore, advocacy and lobbying is crucial and outside actors are important partners who can assist with monitoring and evaluation, giving support to the communities, and sharing the community experience with wider audiences. These recommendations will help support local communities in long-term mangrove conservation and resilience in Samoa.

Testimony

Our once rich mangrove resources supported community livelihoods for generations. Legends claim that the mangroves and abundance of fish and edible marine life were part of an award for bravery granted by Tui Manu’a to Malalatea, a renowned warrior from Toamua village. This environment, however, has deteriorated dramatically because we failed to uphold sustainable fish harvesting practices and cut mangroves for firewood. Urbanisation has also contributed significantly to the decline. Our goal now is to restore our mangroves, which will enhance ecosystem resilience and simultaneously strengthen protection from extreme tidal activities. – Leaoaniu Patolo of Toamua Village

Download the Report of the Community Conservation Resilience Initiative in Samoa here.

[1] Elisara 2006, Customary Land Tenure Review.

[2] GoS 1960, Constitution of Independent State of Western Samoa 1960; also in GoS 1997, Lands Survey and Environment Amendment Act 1997.

[3] GoS 2012a, Population & Housing Census 2011.

[4] Pacific black/grey duck (Anas superciliosa), blue-crowned lory (Vini australis) and the purple-capped fruit dove (Ptilinopus porphyraceus)

[5] Saifaleupolu & Elisara 2015, Biodiversity Audit for Vaiusu, Vaigaga & Vaitele; 2014, Biodiversity Audit for Toamua.

[6] Siamomua-Momoemausu 2013, Mangrove Ecosystems for Climate Change Adaptation and Livelihood; GoS 2012b, Strategy for the Development of Samoa.

[7] The close canopy provided by the mangroves also helps reduce the presence of the invasive myna bird (Acridotheres tristis & Acridotheres fuscus) and the red-vented bulbul (Pycnonotus cafer).

[8] SROS 2009, The Effects of Chemical and Microbiological Contamination on Vaitoloa Mangrove and its Ecosystem.

[9] Saifaleupolu & Elisara 2015, Biodiversity Audit for Vaiusu, Vaigaga & Vaitele; and also in Ellison et al. 2007, Assessment of the Vaiusu Bay Mangroves.

[10] Vaiusu Village 2006, Tusi Ta’iala mo le Vaia Lelei o I’a ma Figota.

[11] Saifaleupolu & Elisara 2014, Biodiversity Audit for Toamua.