Report from the CCRI Workshop in Russia

The indigenous Udege people, one of 48 indigenous peoples in Russia, inhabit the Ussuri taiga – temperate forest on the Sikhote-Alin mountains between the Sea of Japan and the Chinese border, running by the Ussuri river. This area contains the highest biodiversity in boreal Asia, including the endangered Siberian tiger (Panthera tigris) and many other rare species of fauna and flora. The entire Udege tribe includes around 2,500 people, spread over the Primorsky and Khabarovsky administrative territories in the Russian Far East (RFE). Most of them live in about 20 legal entities known as ‘obschina’ (indigenous or tribal communes). Their traditional areas, occupied over the centuries by Manchurians and then Russian Cossacks, now face rapid expansion of logging, hunting, salmon fishing, mining and industrial development.

As a result the Udege communities, traditionally dependent on wildlife, fish, wood and non-timber forest products, are suffering from strong competition over the resources that sustain their livelihoods. Meat and fish play a key role in the diets of the Udege, and their traditional use for Udege livelihoods is recognised as being environmentally sustainable in Russian policy and law. Women have equal rights to men and while they seldom hunt or fish themselves, they play a significant role in dealing with officials, regulations and documents. Thus, they tend to be more aware of legal details and specific problems of fish and wildlife use and management than men, and often fulfill leadership positions in communes and associations.

Russian law formally recognises the existence of indigenous territories and grants special hunting and fishing rights for them. There is a serious discrepancy however between formal rights, law enforcement and management practices, leading to deep conflicts around indigenous priority rights. Regulations regarding privileges are complicated, unclear and different for individuals within a mixed community, and are often changed without informing communities.

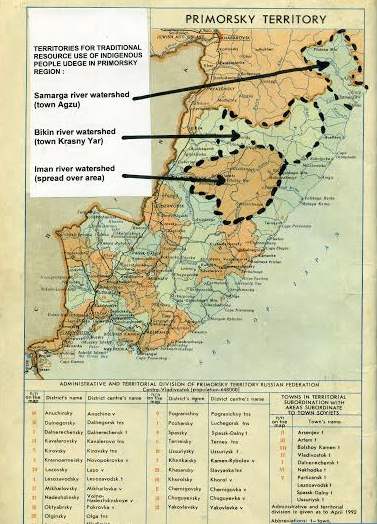

For the CCRI process, three geographically distant watersheds were chosen, different in economic governance and natural resource availability – Iman, Bikin and Samarga rivers communities, each including several legal communes. The assessment process included regular contact with leaders, field visits, and a meeting with the indigenous leaders and the Deputy Governor on 22 May 2015, which led to the adoption of a road map for future work and progress. On 27 July, a full-day capacity building workshop for leaders took place in Iman municipal center, which facilitated the further elaboration of strategies to enhance the resilience of community conservation.

The workshop involved 24 indigenous, scientific and environmental experts from different Udege communities of the region, who discussed all the key issues regarding their conservation, culture, livelihoods, land use, non-timber forest products (NTFP) and other resource rights, as well as access to decision making processes involving the lease of forests and fishing areas. It was significant that no-one from regional and municipal administrations participated even though they were invited several times by NGO BROC.

This illustrates the current attitude of officials in Russia to NGO and civil movements as ‘foreign agents’ opposing the official establishment. Since indigenous people traditionally occupy the most resource rich territories of the Russian Far East and Siberia, including the ‘tiger country’ of Primorye, there are conflicts between their needs, national resource monopolies and authorised poachers.

Despite a series of legal and official statements, indigenous rights and tenure used to be ignored, violated and reduced constantly, which became the key issue in the CCRI workshop, organised by GFC and BROC in Novopokrovka town. Final agreement focused on agreement to develop and maintain public participation and expertise in land lease and use practice, the promotion of Udege culture on many levels and raising legal awareness among indigenous communities.