Une initiative de restauration majeure en Afrique pourrait-elle presque doubler la superficie occupée par les plantations d’arbres provoquant des conflits ?

Par Oliver Munnion, Coalition mondiale des forêts. Publié à l’origine sur germanclimatefinance.de.

L’Initiative pour la restauration des paysages forestiers africains (AFR100) exige 100 milliards de dollars pour aider à financer la restauration des paysages dégradés à travers le continent, dans un effort pour restaurer les forêts et absorber le carbone de l’atmosphère. Aujourd’hui, à l’occasion de la Journée internationale de lutte contre la monoculture d’arbres, les militants appellent les partisans du programme à exclure les plantations d’arbres en monoculture des efforts de restauration.

By Oliver Munnion, Global Forest Coalition. Originally published on germanclimatefinance.de.

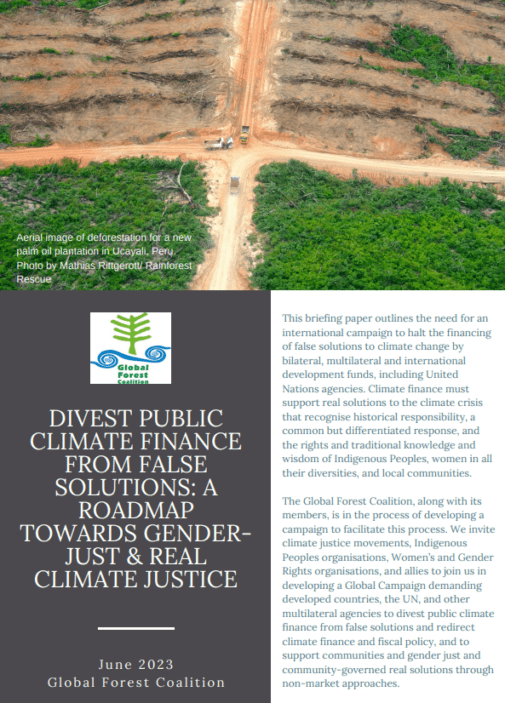

The African Forest Landscape Restoration Initiative (AFR100) wants 100 billion dollars to help finance the restoration of degraded landscapes across the continent, in an effort to restore forests and suck carbon out of the atmosphere. Today, on International Day of Struggle Against Monoculture Tree Plantations, activists are calling on the scheme’s backers to exclude monoculture tree plantations from restoration efforts.

AFR100 is an Africa-wide scheme aiming to restore 100 million hectares of degraded landscapes by 2030. It was launched in 2015 at the Paris Climate Summit and contributes towards the Bonn Challenge, an initiative of the German Government that began four years earlier. 30 countries have since pledged to restore considerably more than the initiative’s original target. AFR100 is now ramping up financing for restoration projects, which vary considerably between community-led forest restoration at one end of the spectrum, and large-scale monoculture tree plantations at the other.

An investigation published today into AFR100 pledges has unveiled large-scale commercial tree plantation targets across half of the participating countries. Put together, these targets amount to a 91% increase in the area covered in commercial tree plantations by 2030. The scheme also relies heavily on other kinds of plantations, often described as “woodlots” or “agroforesty plantations”, which are wide-ranging terms and can have similar impacts.

Despite the fact that some AFR100 pledges were made over five years ago, monitoring of progress towards achieving them is still virtually non-existent in most countries, and there is a shocking lack of publicly-available information on exactly how governments plan to meet their targets. However, the “Bonn Challenge Barometer” assesses country-level implementation of landscape restoration targets in a number of countries including two participating in AFR100, and gives some indication of how pledges are being fulfilled. Alarmingly, “Planted forests and woodlots” account for 82% of Madagascar’s 1.5 million ha of restoration since 2011, and almost 50% of Rwanda’s 700,000 ha.

The science is clear on the fact that tree plantations are a bad option when it comes to restoring landscapes and removing carbon from the atmosphere. A recent scientific paper explained that, in general, plantations hold little more carbon than the land cleared to plant them, and that natural forests are 40 times more effective at storing carbon than plantations (and six times better than agroforestry). The authors state unequivocally that as well as being the most effective option, natural regeneration is also the cheapest and technically easiest to achieve.

However, commercial tree plantations are clearly the favored option where the priority is leveraging private-sector investment. It is far easier to turn a profit through growing eucalyptus than, say, women-led community forest restoration, even if the latter is by far the best choice in terms of climate mitigation potential, biodiversity enhancement and creating sustainable livelihoods. Every hectare of commercial tree plantation expansion is therefore a choice not to restore that hectare to a healthy ecosystem that communities can benefit from directly.

Another important side to this debate is the fact that Africa’s history of commercial tree plantations is one of conflict and neo-colonialist resource exploitation. Although AFR100 is designed to be country-led and is built on collaboration at the national level rather than having a top-down structure, two examples highlight how plantation companies are benefiting from restoration funds at the expense of rural communities.

Whether intentional or not, Mozambique’s pledge to restore one million hectares of land exactly matches another government target to expand commercial tree plantations to one million hectares by 2030. The restoration pledge centres around Mozambique’s World Bank-backed Forest Investment Plan (financed by the Climate Investment Funds), which essentially supports a wholly-owned subsidiary of Portugal-based The Navigator Company – Europe’s largest producer of office paper – to develop a model of plantation forestry involving monoculture eucalyptus that can be rolled out country-wide. Where planting has already taken place, poverty-stricken farming communities have been unjustly dispossessed of their land, given false promises of rural development and intimidated for giving interviews to NGOs. On top of this, eucalyptus plantations are being developed on some of the last remaining areas of fragile miombo forest and grassland ecosystems, making a mockery of claims that this land is being “restored”.

Another example is UK-based Miro Forestry, which claims to be the “the largest developer of new plantations in Africa for the last few years”, and operates over 20,000 hectares of plantations, half of which is eucalyptus, in Ghana and Sierra Leone. Miro’s expansion is being financed by the Green Climate Fund, and is closely linked to AFR100 given that Germany-based UNIQUE forestry and land use GmbH are both an AFR100 technical partner and consultant (contracted to carrying out AFR100’s mid-term review for example) and have a direct financial stake in Miro through the Arbaro Fund, an equity investment firm that Unique co-founded. The World Resources Institute (WRI), one of seven organisations on the AFR100 management committee, has also lauded Miro as a “main impact investing opportunity in the African sustainable forestry space”, and described how the company has “helped restore the previously degraded landscape”. However, Ghanaian NGO Civic Response has leveled numerous criticisms at the company, describing how local communities have not been consulted and how the plantations have resulted in a loss of income and food sovereignty locally. On top of this, a large number of farmers were evicted without compensation by Miro from one of their concession areas, resulting in a long-standing legal battle.

Few conservationists would agree that clearing land to plant eucalyptus, only for it to be harvested ten years later and turned into short-lived products or worse still burned for energy, could possibly be considered restoration. AFR100 and its backers should acknowledge this and exclude tree plantations from the scope of restoration efforts, and rule-out financing them in the name of landscape restoration.

Photo credit: Justiça Ambiental