The “Sustainable Iron and Steel Production” project has been running since 2014 and is due to end later this year. It is being implemented by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) and has received over 7 million USD from the Global Environment Facility (GEF). The project aims to reduce emissions from Brazil’s huge iron and steel sector in Minas Gerais through financing more efficient charcoal production methods (up to a 10% increase) that emit less methane to the atmosphere, so that “sustainable charcoal” is used instead of charcoal produced from more carbon-intensive traditional methods.

Brazil’s iron and steel sector is unique in that it uses significant amounts of charcoal instead of coal. Brazil is the world’s largest producer of charcoal for this reason, and produced 5.2 million tons in 2017, 90% of which was used by the iron and steel industry. 80% of the iron and steel industry’s charcoal is produced from wood from eucalyptus plantations. Iron and steel companies in Brazil also tend to be vertically-integrated and own and manage eucalyptus plantations to produce charcoal from. Consequently, Minas Gerais has 1.4 million hectares of eucalyptus, more than any other state in Brazil.

The social and environmental consequences of “sustainable charcoal” production

On-the-ground research to document the impacts of eucalyptus plantations for charcoal production in Minas Gerais reveals a far darker side to the green image presented by the industry and its supporters in GEF and UNDP. Over the past five decades, huge areas of common land have been taken from the geraizeiros, the traditional communities of Minas Gerais, and turned into monoculture eucalyptus plantations. These plantations have deforested highly biodiverse forest savannas, dried up and polluted water courses and threatened the whole northern region of the state with desertification.

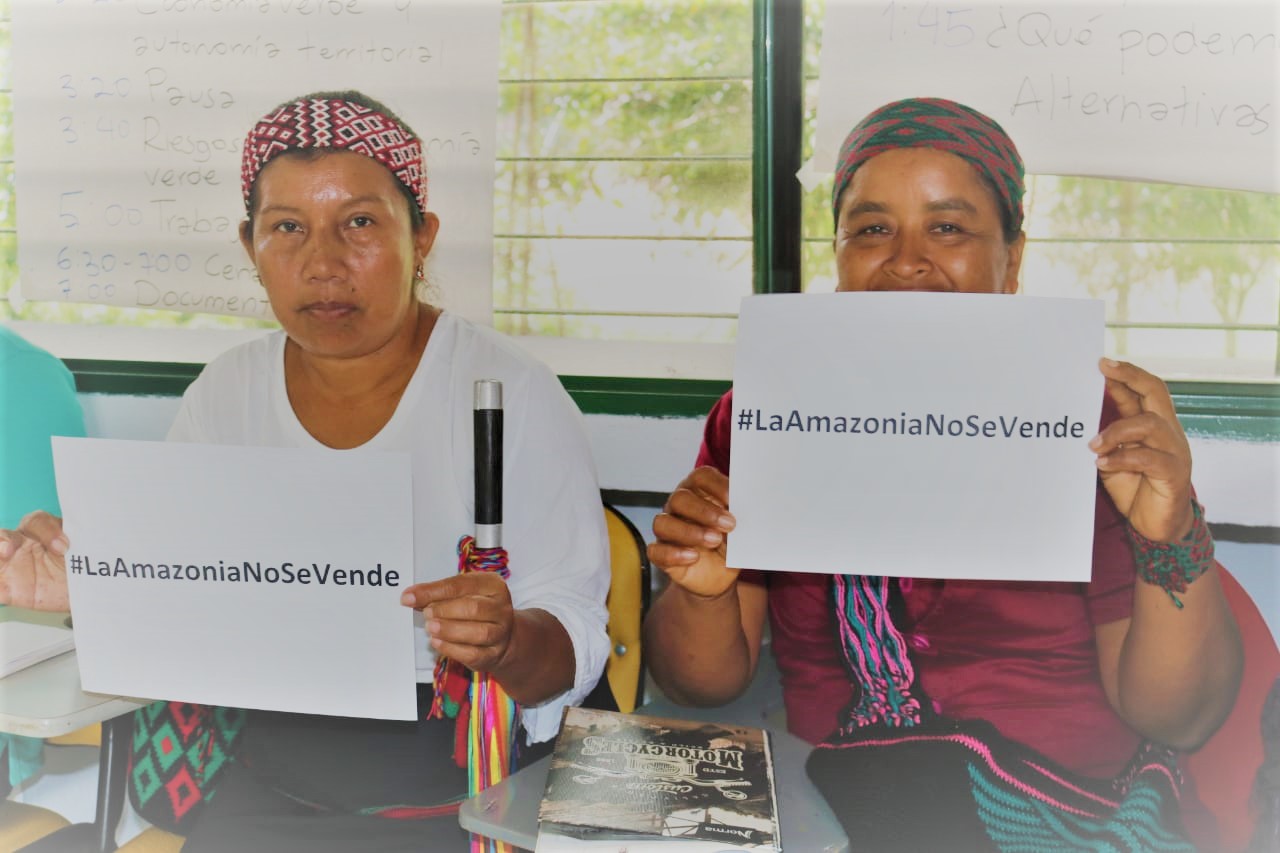

Through fraudulent means or state-sanctioned leases, the traditional peoples of the area have lost access to land that they should have had rights of tenure over, and which for generations ensured their food sovereignty and sustained their cultural practices. Now they find themselves surrounded by eucalyptus, with dwindling populations and little hope of protecting their rural existence.

Four companies with highly questionable track records have been directly subsidised to produce so-called “sustainable charcoal” through the project. The case study describes how Plantar and Rima have been associated with substantial historical landgrabbing, and are still singled out by communities for the impacts that their plantations are having on biodiversity and water courses. In addition, Rima was recently exposed as being involved in the “Charcoal Mafia” which fraudulently sourced illegal charcoal produced from deforestation at significantly lower prices. Another company, Vallourec, has in the past been complicit in violence against local communities and the murder of a farmer through the actions of its armed guards. The giant steel-producer ArcelorMittal has also been fined numerous times for air quality breaches and has recently had to relocate a large number of families from their homes because of a dangerous tailings dam at risk of collapse in one of its mines in Minas Gerais. Finally, charcoal producer PCE/Cossisa (initially contracted by UNDP but subsequently withdrew from the process) reportedly subjects its employees to poor working conditions with weak health and safety practices.

The project has not carried out an assessment of the social and environmental impacts of eucalyptus plantations, and despite claiming to involve civil society stakeholders has limited this to just WWF Brazil and Imaflora, a non-profit that is being paid by the project to certify charcoal operations. The project has also ignored gender completely, disregarding for example the evidence of the gender-differentiated impacts of eucalyptus plantations in Brazil where women have been exposed to violence and sexual harassment, have even less secure land rights and are even more vulnerable to loss of livelihood.

What the project is actually trying to achieve is reducing the production costs of so-called “sustainable charcoal” so that the industry can create an economic and steady supply of socially-acceptable charcoal that meets legislation and is eligible for carbon credits (which can offset the increased production costs).

Flawed carbon accounting hides climate impacts of “sustainable charcoal”

Despite the claim that the project is reducing wood demand it is more likely that the new charcoal facilities will be used alongside existing traditional methods rather than replacing them, thereby increasing production capacity and overall demand for eucalyptus. This was certainly the case for the first operational charcoal facility funded through the project. Financing increased production in this way incentivises plantation expansion and worsens eucalyptus-related impacts in the state.

In terms of emissions reductions, the figures quoted by the project so far are based on a flawed carbon accounting methodology that treats all wood sourced from a plantation as “renewable” (even if land was deforested to create the plantations), and therefore ignores any carbon dioxide emissions when it is turned into charcoal and burned. More and more scientific evidence refutes this approach, including a recent study showing that even burning plantation thinnings increases carbon pollution in the atmosphere for more than four decades. This is due to the time it takes for carbon to be accumulated by new trees in the plantations, and is a significant factor even at the relatively short rotation cycles associated with Brazil’s eucalyptus plantations. If the current science were to be applied to this project it would be clear that there is no such thing as “sustainable charcoal” at this scale, no matter how efficiently it is produced.

Another highly problematic and closely linked aspect to this project is that it aims to bring down the costs of “sustainable charcoal” production by making it eligible for internationally-traded carbon credits. The technological developments that the project is facilitating aren’t necessarily sophisticated–the first operational charcoal facility burns the methane produced from the process in a chimney rather than releasing it to the atmosphere (as happens in traditional charcoal production), for which emissions reductions are claimed. Awarding carbon credits for such a process really would expose the system for what it is: a carbon con that lets both the credit seller and buyer claim to be reducing emissions when in actual fact amount of carbon in the atmosphere is increased by both processes.

Message to the German government: stop financing false solutions to climate change

GEF and UNDP’s project is a clear example of misdirected climate finance that bows to private-sector interests and protects the status quo. Instead of tweaking a highly polluting, land and resource-intensive process by fudging how carbon is accounted for, international finance for climate change mitigation should be transformational, and directed towards the root cause of the problem. In this case, financing a reduction in demand for iron and steel through for example reducing the production of new private cars, or airplanes, or football stadiums, would be far more effective.

Similarly, rather than funding private sector tree plantations a far better option is to fund community-led forest restoration. A recent paper shows how natural forests are 40 times better at storing carbon than plantations, and that’s without even considering all of the additional benefits such as sustaining the livelihoods of forest-dependent peoples, protecting biodiversity and regulating hydrological cycles.

In directly subsidising highly polluting industries GEF and UNDP show themselves to be a part of the problem rather than the solution. We call on the German government and BMZ to use its influential position within GEF and other international climate finance mechanisms to ensure that public money is redirected away from harmful tree plantation and bioenergy projects, and towards community-led conservation and restoration efforts and other real solutions to the climate crisis.

Guest post by Oliver Munnion, Global Forest Coalition