From the village to the United Nations: The journey for Peasants Rights

Photo credit: Hannes Jung

By Muhammad Ikhwan*

“In 2004, the idea to make a new human rights instrument for the protection of peasants rights were getting ridiculed even in the United Nations,” says Henry Saragih. Henry, a peasant from North Sumatera, Indonesia, was referring to the initiative of 200 million-strong La Via Campesina, the international peasant movement, to push for their Declaration of Peasants Rights – Women and Men to be discussed as a human rights instrument within the UN Human Rights Council.

Recently, this important initiative was discussed by civil societies, NGOs, academia and some governments of Europe in Schwäbisch Hall, Germany from 7-10 March 2017. As the effort for protection and recognition of peasants rights is gaining momentum, a “Global Congress” was organized to give the initiative more visibility.

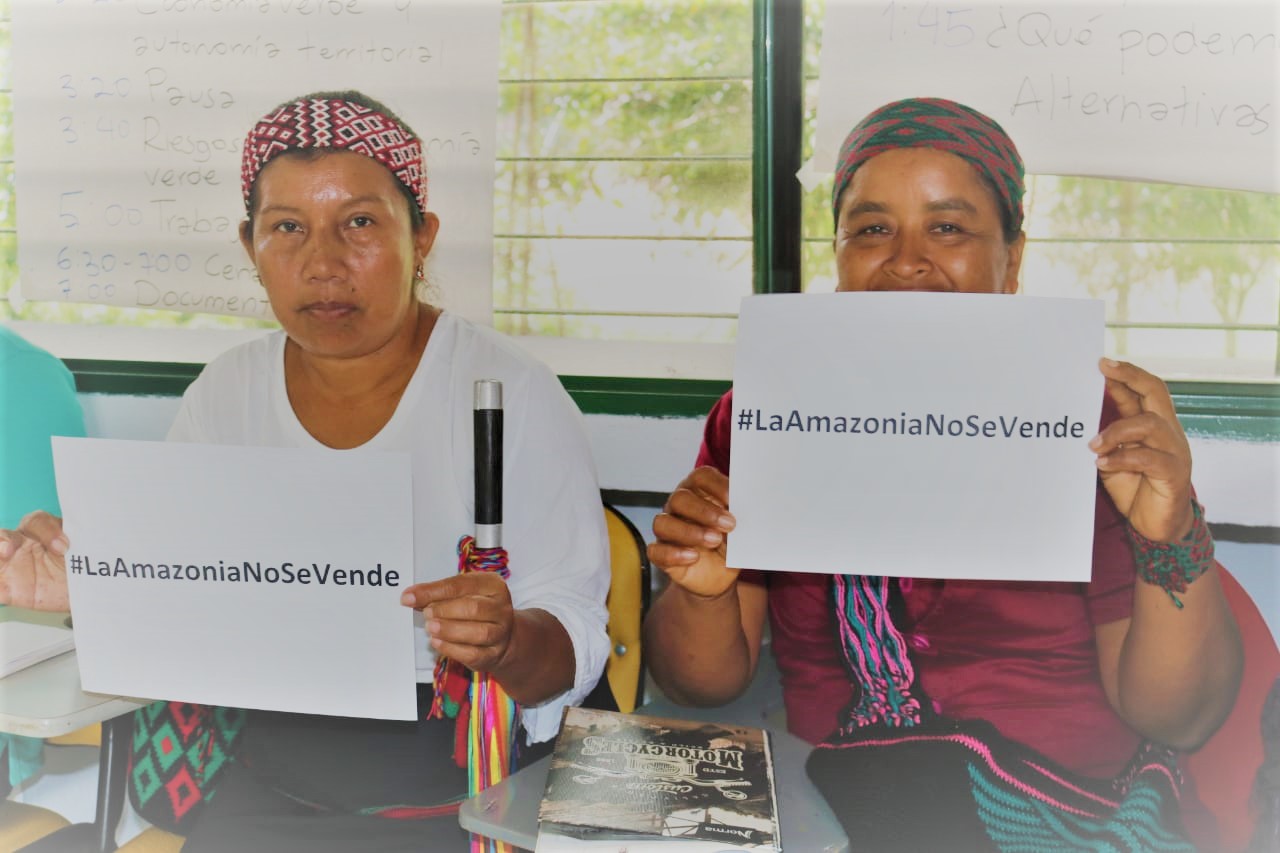

Most of the participants feel that the need for a human rights instrument for peasants is becoming more and more urgent. Peasants and other people working in rural areas, producers of the food on our table, continue to face criminalization, discrimination, and persecution. These groups are very vulnerable to human rights violations: we can see land grabbing has been happening in many parts of the world and this expropriates peasants from their land. Expansion of plantations like palm oil forced peasants and indigenous people out from their land and territory, peasant women in rural areas are still suffering gender discrimination, and low income and lack of access to means of production are evident in rural areas around the globe.

“Despite years of campaigning for a better recognition and protection of the rights of peasants, displacements and criminalization continue affecting hundreds of thousands peasants globally. Hunger and malnutrition, unemployment and poverty all have something in common: they are more prevalent in the rural areas or countryside. Because of this, most people coming from the countryside have been exploited,” Elizabeth Mpofu stated in her plenary speech.

Not only exclusive to peasants, or small food producers related to land, but this initiative has been developed to include all people working in rural areas. In the latest UN draft declaration, we can find that the declaration also applies to any person engaged in artisanal or small-scale livestock, pastoralism, fishing, forestry, hunting or gathering and handicrafts. Crowds in the Global Peasants Rights Congress also proves this provision: representatives from fisher folk, indigenous, beekepers, pastoralists, nomads, women, rural workers and even trade unions were present voicing their concerns.

On the first day of the congress, these groups presented their support to the current process–plus legal analysis on the value added of such a declaration if adopted by the UN. On the second day, participants gave their inputs on the current draft UN Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas, emphasizing on the rights to land, rights to seeds, rights to decent income, rights to biodiversity and traditional knowledge, and also criminalization, persecution suffered by the groups. The Congress really showed how the current draft UN Declaration has been shaped: from the village to the UN. It was some 16 years ago that the idea was discussed in a small village in Sumatera, then multiplied by the same process in Paraná, Limpopo, Granada, and many villages where members of La Via Campesina were. This is not a mere paper; this is a venture for the betterment of human rights and it is coming from villages to the human rights system in Geneva.

When discussing the importance of the initiative, Taghi Farvar, President of the ICCA Consortium and an indigenous said “erase every doubt you have”. He continues, “This declaration will be a useful tool–for further elaboration of our rights, and for defending ourselves.”

In the United Nations itself, the initiative will undergo the 4th session of negotiation–meaning the content of the draft declaration will continue to be shaped by UN member states, civil society and other parties. The Bolivian Ambassador, Nardi Suxo Iturri, was adamant and noted that the process will move forward. “This is a mandate from our country, and our president, who is also a peasant and an indigenous,” she said in the congress. Participants then responded with a huge applause.

The Congress was a great success. It also reflected a strong solidarity from many organizations, movements, and different parts of the world. The final manifesto also made a crucial call for interconnected struggles. The struggle continues: even when the future is bright for a UN Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas, the road is still long for its implementation. Peasants, and us, still have to fight in our daily lives, not only for our human rights–but also for the rights of Mother Earth.

*Muhammad Ikhwan is La Via Campesina staff for the rights of peasants collective. He also works for the Global Forest Coalition around social media and website