Stalemate in the WTO but…. No permanent solution for the right to food

This was originally published in the Rosa Luxembourg Foundation website: https://rosaluxspba.org/en/right-to-food/

December 22, 2017

By Mary Louise Malig*

Social movements, trade justice activists, forests and environmental organizations and people campaigning against the World Trade Organization (WTO), are celebrating the world over the collapse of the talks of 11th WTO Ministerial held in Buenos Aires from 10 to 13 December, 2017

This, however, is just a partial victory as the right to food and sovereignty from unfair trade rules remain in peril.

It is not the first time that the WTO negotiations have broken down into a collapse with negotiations even being suspended indefinitely by former WTO Director General Pascal Lamy in 2006. These collapses may have had different triggers but mostly it has been because of the intransigence of so-called “developed countries” to give any concessions to the “developing countries” in the area of agriculture.Sending a message from Buenos Aires

The stalemates have also been caused by the rich countries pushing for issues that would be beneficial to them such as trade facilitation, investment, government procurement and competition, while ignoring long-standing demands of developing and least developed countries. These demands were promised to them as part of the Doha Development Round launched in 2001, such as numerous promises of bringing development to the developing and Least Developed Countries (LDCs), eliminating trade-distorting subsidies of the developed countries, and ending dumping or the practice of flooding markets with goods below their cost of production.

The elimination of export subsidies, for example, promised in 2005, passed the 2013 deadline and was only finally fulfilled in 2015. But without meaningful reforms in the US and EU domestic subsidies, these had the same effect as export subsidies, flooding developing markets and undercutting small farmers. Studies show that heavily subsidized EU milk powder enters the market of Burkina Faso at only 34 cents, whereas the the local cost of production of milk powder by local farmers is 91 euro cents per litre. This disparity in price is an emblematic example of the inequities built into the WTO Agreement on Agriculture (AoA).

Receiving but not giving

Still on agriculture, the contentious “peace clause” that was the centre of controversy in Buenos Aires, was also about the refusal of countries such as the US to give something as vital as the ability to let developing countries have public food stocks and subsidies for their subsistence farmers to guarantee their national food security. This hypocrisy of the rich countries being able to continue through various loopholes in the AoA to provide trade distorting trade subsidies to their agribusiness but blocking the poorer countries the right to guarantee food security and provide their constituents the right to food, a universal human right.

In simple terms, the “peace clause” was given as a concession to countries of the Global South to appease their original demand for an amendment to the AoA so that they could provide domestic support to small and subsistence farmers, without breaching the limits set in the AoA. This demand of the developing countries was made in the spirit of guaranteeing food security to their people and for public stockholding purposes.

But instead of giving this amendment, the rich countries gave a temporary “peace clause”, meaning that poor countries could provide that domestic support and breach the AoA limits and not be sued under the WTO Dispute Settlement Mechanism for violating the rules of the WTO AoA. This “peace clause” was promised to be replaced with a permanent solution that would allow them to have stockholding and that the deadline was the 11th Ministerial in Buenos Aires.

This “peace clause” agreed to in Bali came at a high cost to developing countries as they in turn had to agree to the comprehensive Trade Facilitation agreement, an issue that had long been on the wish list of transnational corporations (TNCs) and developed countries. This agreement was a great victory for the newly elected Director General Roberto Azevedo, as this was the first ever agreement of the WTO since it was established in 1995.

Azevedo, a known supporter of business had even earlier stated in an interview on a famous Brazilian TV show, in May 2013: “I believe TNCs love the WTO and they really want the WTO to be able to lower barriers to trade because they won’t be able to do it alone. They really won’t! They need that these negotiations take place in the WTO, for example trade facilitation. What we are negotiating in Bali now is of great interest for TNCs. I know this also because in my former position as Brazilian Ambassador in Geneva I received visits from CEOs, from important people representing TNCs that want to facilitate trade.”

Despite the high stakes paid for a measly “peace clause”, there were still hurdles and further concessions being demanded in order to end the “peace clause” and give a permanent solution. In truth, developing countries had already “paid” for the permanent solution by agreeing to the Trade Facilitation Agreement in Bali. However, in Buenos Aires, they were being asked to pay yet again, by agreeing to even more demands from developed countries. But even that was not enough for the US, as it walked away from the negotiations, leaving developing countries once again empty handed and left with no permanent solution.

End the WTO!

The inequities of the WTO Agreement on Agriculture is just a sample of the rest of the inequalities of the rules of the WTO. The WTO was never and will never be about providing a level playing field nor improving the welfare of the poor by delivering so-called development. The WTO is about providing undue advantage to the big and powerful, or in a simple visual to imagine, the WTO rules favor the sharks over the sardines.

The most worrisome part of the draft texts in Buenos Aires was the lack of reference to the so-called Doha Development Agenda. The specific impact of politically killing off the Doha round is that all the “development” aspects of that round and all the demands that countries of the Global South had included there will be lost. The Doha round had a single undertaking principle – nothing is agreed until everything is agreed – and this had been a way of holding back the extreme liberalization plans of rich countries and TNCs.

There is no place for the WTO in a world that puts the planet and humanity first. As the Economy for Life in an Earth Community, a living document produced at the Economic Justice assembly parallel to the 9th WTO Ministerial in Bali, Indonesia, and brought to the Fuera OMC Peoples Summit in Buenos Aires as a contribution to the development of proposals and alternatives, states:

“Defend and guarantee the rights of those that are most marginalized by the current capitalist and neocolonial system: women, indigenous people, peasants, migrants, domestic workers, elderly, LGBT community, cultural minorities or even majorities that have been displaced by the powerful (…) As our Vision states, the Economy for Life is an economy where the fundamental needs of every being and Mother Earth are guaranteed to promote the creativity, humanity and happiness of life. Where solidarity, complementarity, diversity, peace and the well-being of the Earth community as a whole have replaced the greed, ambition, competition, individualism, discrimination, violence and destruction of our Mother Earth generated by the logic of capital. We will achieve this vision by supporting each other’s struggles at local, national, regional, and international levels, across sectors, across issues, across borders. The solutions are in our hands, the hope is in our hearts, and the power is in our solidarity. We will change the balance of forces, reclaim our future, change the system and realize an Economy for Life for Our Earth Community.”

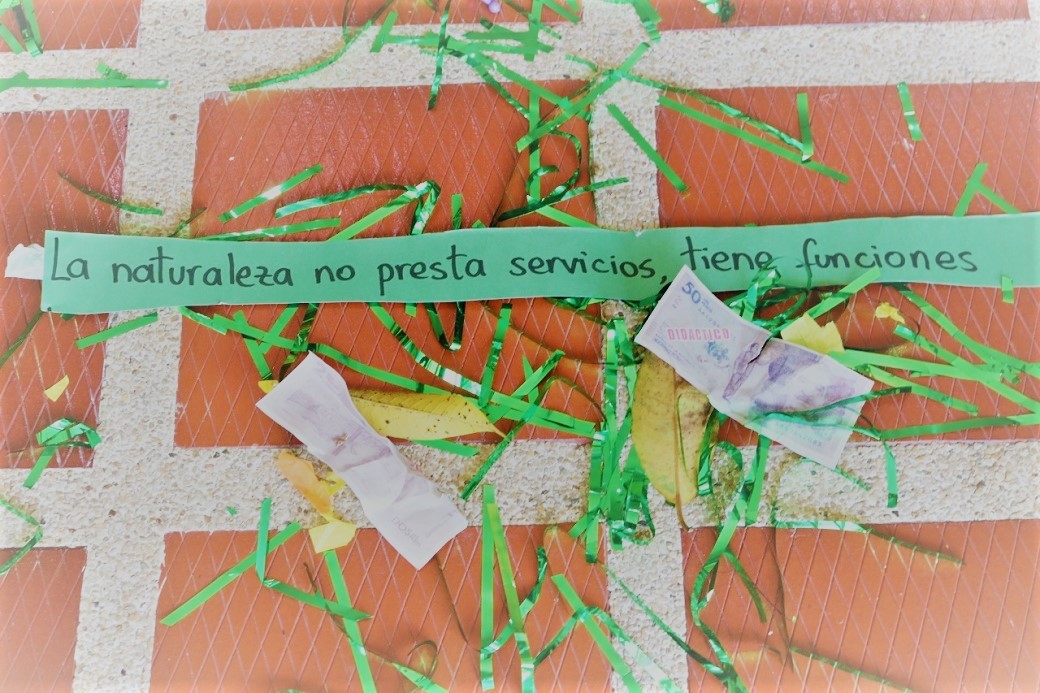

Foto: Fuera OMC

*Mary Louise Malig is a trade analyst and campaigner from the Philippines and now currently based in Bolivia. She has written on the issues of trade particularly the World Trade Organization (WTO), climate change, agriculture and the green economy. She is co-author of the book, The Anti-Development State: The Political Economy of Permanent Crisis in the Philippines and author of a number of other papers and publications. Malig is currently Campaigns Coordinator of the Global Forest Coalition.